A lot of casinos in Las Vegas do this. You can get a cocktail, the cheapest steak you’ll ever find and in the evening you can see a nightly show from someone who was in the charts when you were in high school. But some of those things are more remunerative for the casino than others. The place they make their money is the gambling.

The team behind Finixio is also behind a massive network of crypto and gambling projects. To understand how these guys make money off a raft of crypto projects that keep changing, yet mysteriously all look and perform the same, you have to look under the carpet a bit and see how crypto projects operate.

Listen to the entire episode here

In theory, crypto projects are meant to work like this

- You come up with a new token or a new idea for something on the blockchain. This can be a token, or it can be something that just uses tokens to facilitate something else — a game, an organization, or something else

- You sell some of the tokens before you launch the project. This pays for development costs, then when you launch the project, people who bought early get their tokens. Usually they buy at a reduced price. This is called a presale

- You launch the project and people use it, buying the token and trading it

Crypto token sales are susceptible to a group of types of frauds known as rug pulls, from the image of the team behind the project pulling the rug out from under the community of participants and investors.

Rugpull 101

Rug pulls happen when the team behind a crypto project pulls all the money out of it and bails. Investors are left holding worthless tokens. They can take the form of:

Liquidity pulls

The team or another actor removes liquidity from a token pool (reduces the amount of circulating tokens). This makes the value drop because no-one can buy or sell.

Fake projects

Scammers create a project, grow a community around it, and sell tokens, before disappearing with the money and leaving participants holding tokens that aren’t worth anything and were never expected to be.

Pump and dump

The price is pumped by the team or other actors buying tokens in a coordinated way to make them seem like they’re in demand. The team then sells (dumps) the tokens at the new, higher price, making a return on their investment but crashing the price for everyone else.

Exit scams

The team simply takes whatever they’ve managed to make and abandons the project.

Rugpulls come in two main flavours, hard and soft.

Hard rugpulls happen when the team simply abandons the project, takes all the money they can and runs.

Soft rugpulls happen when developers abandon the project quietly, selling their tokens and leaving their community to figure out what happened. Soft rugpulls themselves come in two subtypes: fast and slow, and the distinguishing factor of a slow rugpull (apart from being, you know, slower) is that it’s relatively much harder to detect than a hard rug where the team just pockets the tokens and runs.

(Sometimes the terms ‘soft’ and ‘slow’ are used interchangeably, but they mean more or less the same thing: hard rugs manipulate blockchain mechanics and slow/soft rugs use market manipulation.)

A slow rugpull is the hardest to prove, but it can also be the most remunerative — especially if it’s not done in isolation, but as part of a wider strategy.

The art of the slow rugpull protocol

Finixio has been accused of multiple rug-pulls over the years. Because of the nature of crypto, it can be difficult to conclusively show exactly what has happened, but there is a pattern:

1: Projects get hyped through the Finixio team network of crypto and gambling focused websites (that often used to be OK tech sites)

2: Those projects develop a user base

3: They run a token presale, where select participants can buy tokens before the project is up and running

4: Token releases are manipulated by delaying release to presale buyers

5: Other projects also operated by the same organization are hyped in media assets they own or control, and their price rises — perhaps because the team is buying tokens — making it look as if the present project may also produce value for investors. The token price rises, encouraging investment

6: The token price crashes or fails to improve, the project’s other goals fail to materialize, the project is effectively abandoned; alternatively, the project continues live, and there’s a ‘soft rug pull’

Presales are a key component of the crypto economy. Theoretically, they let projects generate investment they can then use to finish building their infrastructure, and this is sometimes true (ETH, for instance).

But they’re a favourite tactic of scammers, for one reason: you buy the token early, but it’s normally released at the same time as tokens are released for sale on the blockchain. What’s more, while you’re buying a token that exists on the blockchain, your purchase takes place off-chain.

This means a company can offer token presales, take the money, and run. And it can be months before investors realize they’ve been scammed and their tokens are never going to arrive. What’s more common is that they do arrive but have lower value than predicted and never gain value. Meantime, unlike onchain purchases, the company itself is responsible for keeping financial records, and they might just… not. Presales are an ideal way of disconnecting money from its source.

Rolling rugpulls: the pattern of price manipulation

Rather than executing multiple rugpulls, the evidence appears to suggest Finixio/Clickout are ‘rugpull farming’ — using the existing projects that have already been ‘soft rugpulled’ to reflect well on their up-and-coming projects and encourage investment, and teasing the remaining community with promises of future developments that never happen.

Marketing the pump and dump: Dogeverse and Slothana, 99 Bitcoins and more

If that were the case, we’d expect to see a coin like Dogeverse show a sharp spike in price on becoming publicly available, followed by a drop-off, a slight recovery, and then that pattern again, always ending slightly lower than it started, before it finally bottoms out.

https://www.coingecko.com/en/coins/dogeverse

Like this.

That’s the Dogeverse cross-chain coin released in June this year. Dogeverse was identified by Ben Solwin as a Finixio asset, and is listed in the letter from their lawyer received by a crypto Youtuber last year (see below for more on that!).

It’s also heavily promoted on 99 Bitcoins:

These are 99Bitcoins’ videos in the runup to the launch. For more on this asset see here if you missed it.

You can see three of them directly promote Dogeverse.

To support the legitimacy of the coin, the website shows it being featured in multiple crypto-oriented publications:

Funny, two of those are confirmed Finixio assets, bitcoinist might be. Only CoinTelegraph isn’t directly owned or controlled by the Finixio team. Instead, it has a subsidiary iGaming division staffed with Finixio/Clickout staffers.

The Finixio team is basically doing to CoinTelegraph what Forbes Marketplace did to Forbes.

To put it another way: there is no actual press coverage or scrutiny of this stuff at all.

Just advertising.

In the Dogeverse ‘deep dive’ (actually a breathless promo) uploaded at the end of May, just before the end of the Dogeverse presale, the 99 Bitcoins host points to this graph showing the Slothana token’s activity immediately post presale as evidence that a token can deliver stellar performance right from the start and reward investors who bought in the presale:

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=PfTF90lXqKw

Note that it’s a fifteen-day period.

The team behind Slothana, says the host, is ‘doing everything right,’ including listing on centralized exchanges, and ‘I would imagine a similar thing is going to happen with Dogeverse as well.’

https://coinmarketcap.com/currencies/slothana/

Here’s Slothana’s price performance since the video was made. The section shown by 99 Bitcoins is way over there to the left.

As for the rest, I guess you could say it was similar to Dogeverse’s performance.

One striking similarity is that anyone who bought the token in the presale expecting it to retain or gain value would now be out of pocket.

In the case of one memecoin operated by Finixio staff, we have found what appears to be striking evidence of market manipulation.

To read more about that, stick with us or go to the Wall Street Pepe section.

Back to price history, it’s a similar story with 99Bitcoins’ recently-launched token:

https://coinmarketcap.com/currencies/99-bitcoins/

All three of these coins got a mention in Net Crypto’s cease and desist letter, remember, meaning that lawyer’s client owns, controls or is affiliated with the teams behind these coins: companies don’t share lawyer letters, they’re not Ubers home.

Slothana’s token saw a single purchase worth $54,000 in the early days after its release, reported in Techopedia’s French pages as ‘a whale (large investor)’ who ‘was spotted by community members on May 15, 2024’; purchases by large, often institutional investors can be a sign that a token’s value is high enough and stable enough for larger players to be interested, as well as helping to maintain that value and stability.

https://www.techopedia.com/fr/crypto/rumeur-slothana-listing

(This article has now been taken down, but a brief summary of its contents and links to it survive archive-scrubbing and website pruning via these French– and English-language subreddit threads.)

But one way a sign like this can deceive is if the ‘whale’ is the development team buying to pump and spreading those purchases across multiple wallets, in order to disguise their activities.

In the meantime, crypto news outlets covered the presale of two other coins. Before those presales even began, Coincierge’s Manuel Lipitz told readers: ‘Dogeverse and Slothana are exploding! These two meme coins could follow.’

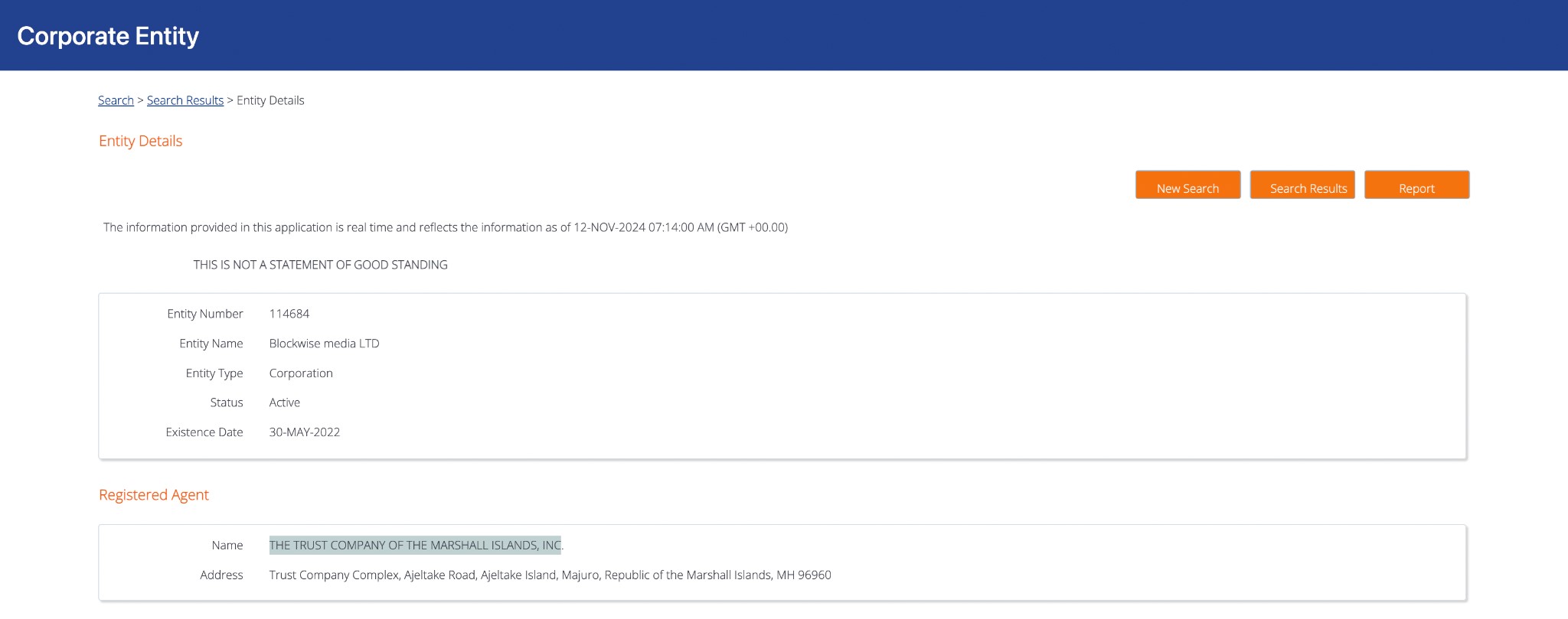

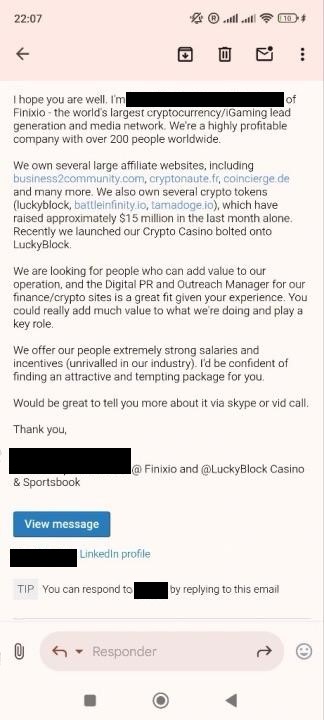

It was hard to track down ownership of coincierge.de since it’s registered in the Marshall Islands, where a single entity acts as agent for all foreign businesses and ‘disclosure of names [of shareholders and officers] is voluntary.’

However, in 2022, the breakthrough Danish TV documentary ‘Det Graenselose Bedrag’ (The Borderless Deception), hosted by Cecilie Beck, was able to show that concierge.de is a Finixio/Clickout asset.

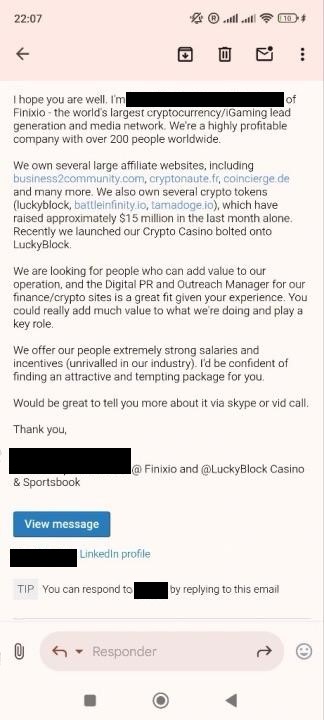

I thought that was the best I was going to get, but recently a source was kind enough to share with me a recruitment email from Finixio/Clickout in which they openly claim ownership of Coincierge:

Check out the crypto projects that they claim ownership too — and the amount of money they’re boasting about. $15 million in the last month?

At the time of the Coincierge story, June 9 2024, Slothana’s price did ‘surge.’ It was the last time it would ever be in the green.

https://coinmarketcap.com/currencies/slothana/

(That hasn’t stopped Coincierge running stories trying to flog this increasingly deeply buried dead horse well into January this year, when the price is about 20% of its launch price and a mere 6.5% of its peak.)

Dogeverse’s price was on the rise in June too:

https://coinmarketcap.com/currencies/dogeverse/

Just two days later, it, too, would go into the red, and stay there. These price surges provided Coincierge with its story, and with some dubious proof that these types of memecoins could be profitable.

The two coins Coincierge suggested might be ‘next meme coins… [that could be] already be in the starting blocks, with the potential for similarly high returns’ in June this year were Base Dawgs and Sealana (both identified by Ben Solwin as Finixio/Clickout Media projects; Sealana was mentioned in the Cease and Desist, while Base Dawgs is identified as a client by CryptoPR, which in turn was co-founded by Finixio/Clickout’s Adam Grunwerg).

Were they right?

https://coinmarketcap.com/dexscan/base/0x46468412ccdbeea32934f6eaa41c7b9d986856fd/

Looks pretty similar to me.

So does this:

https://coinmarketcap.com/dexscan/ethereum/0xda83863e335e06f4f9ad3ac358257eac1e0aa232/

Except worse.

These two coins were hyped ahead of their ICOs by 99Bitcoins too, which included Sealana along with Dogeverse in its ‘top 5 Memecoins’ video in May:

TOP 5 MEME COINS TO BUY IN MAY!! 50X YOUR MONEY!!

Then, on June 18, seven days before the launch of Sealana and while the presale was still open, this video gave the coin very similar treatment to the hype 99Bitcoins showered on Dogeverse back in May:

Last Chance to Buy This New 100X Potential Meme Coin – SEALANA! $5 MILLION RAISED!!

Where’s that $5 million now, when Sealana is no longer trading?

Increasing boldness: higher stakes, faster pulls

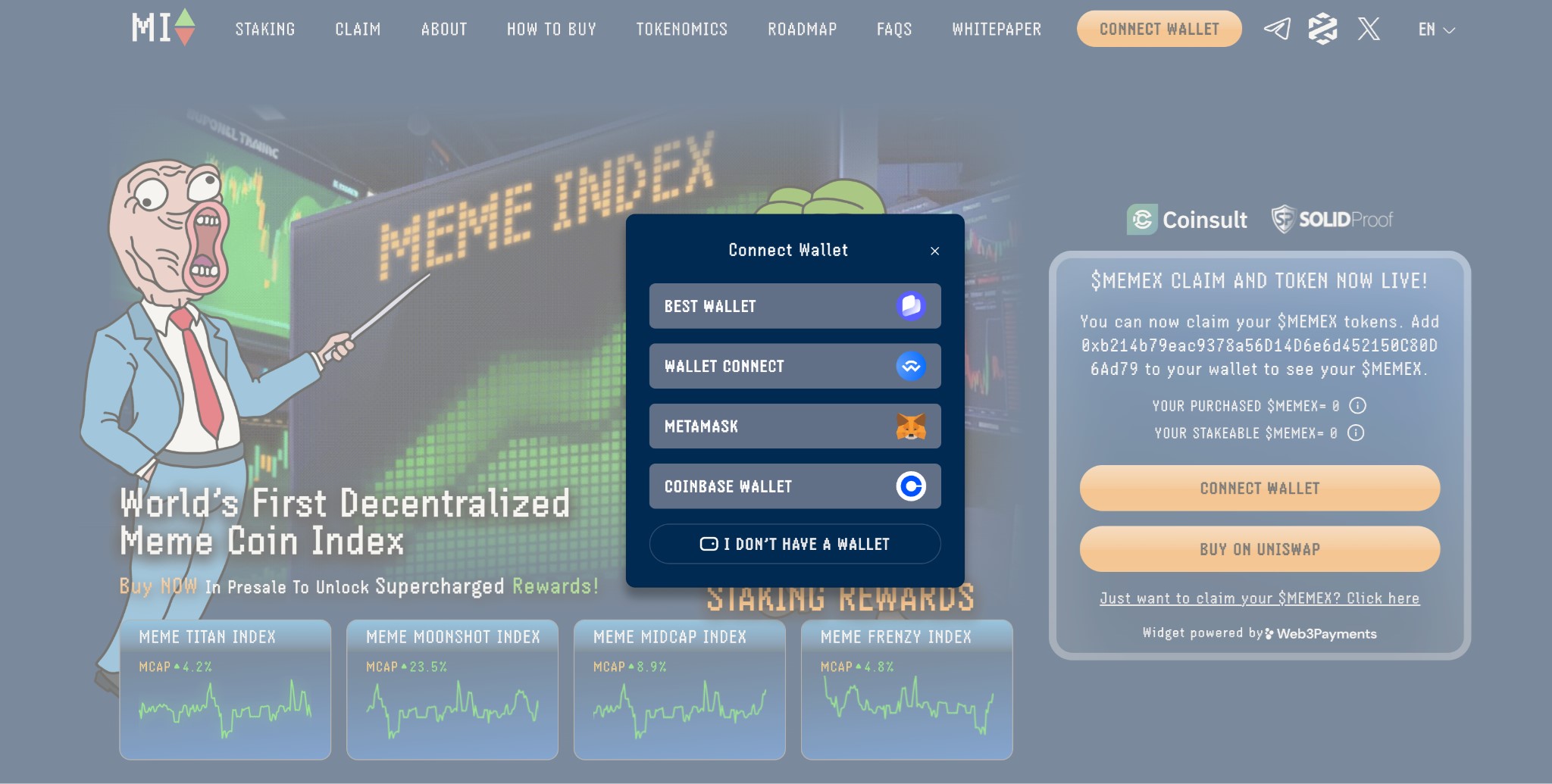

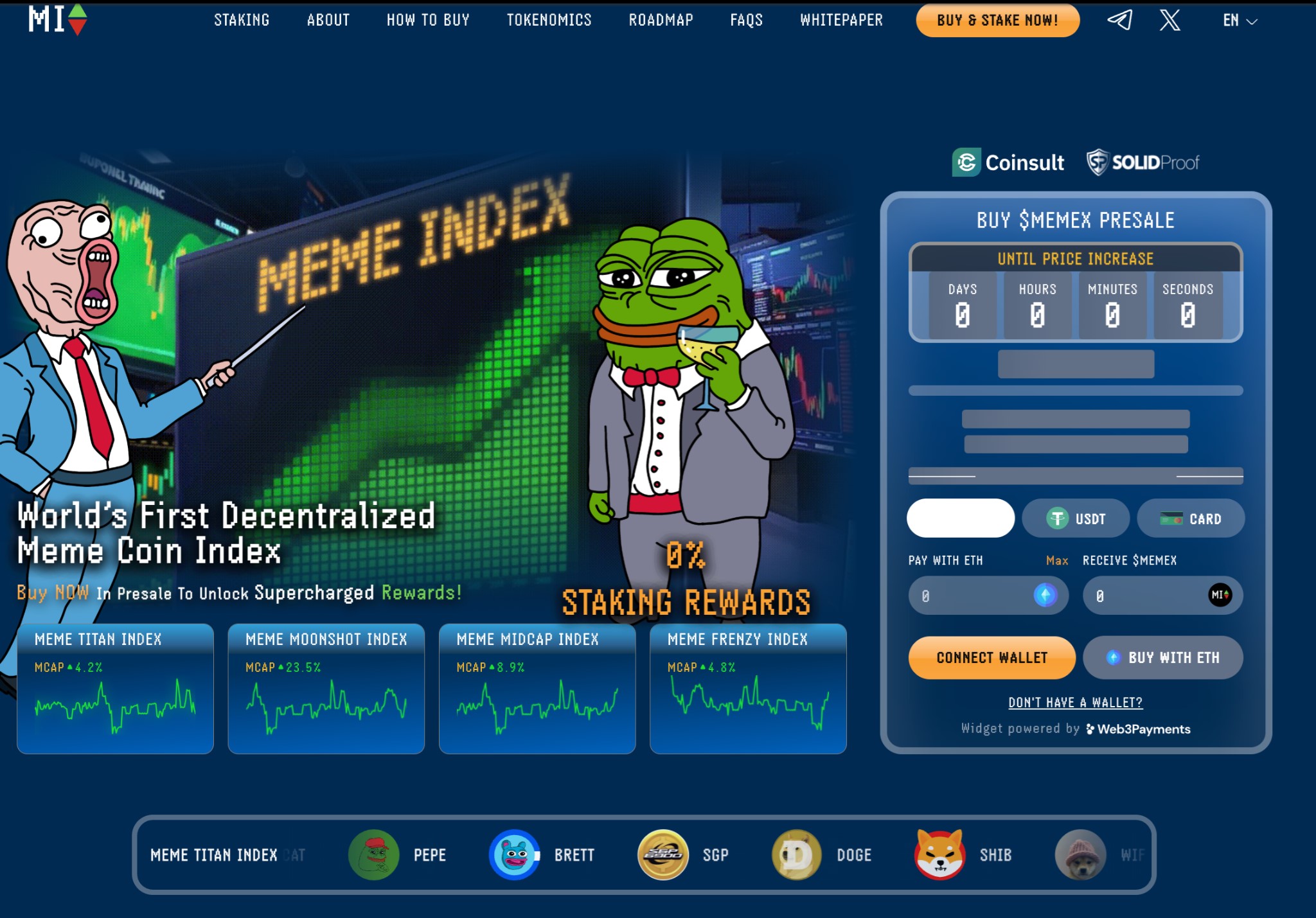

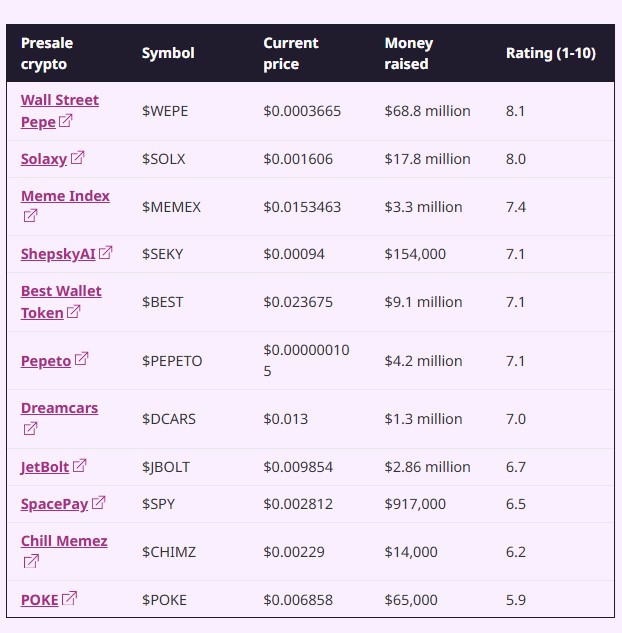

Over time we’ve seen a pattern of increasingly large pulls that look more and more blatant. The most serious of these that we could get solid information on is Wall Street Pepe, and we have real direct evidence of wrongdoing there. But the latest effort, MEMEX, also deserves a look. Billed as the ‘world’s first decentralized meme coin index,’ MEMEX occupies the domain of someone’s defunct 2009 blog, which as of 2013 looked like this:

https://web.archive.org/web/20131008164355/https://memeindex.com/

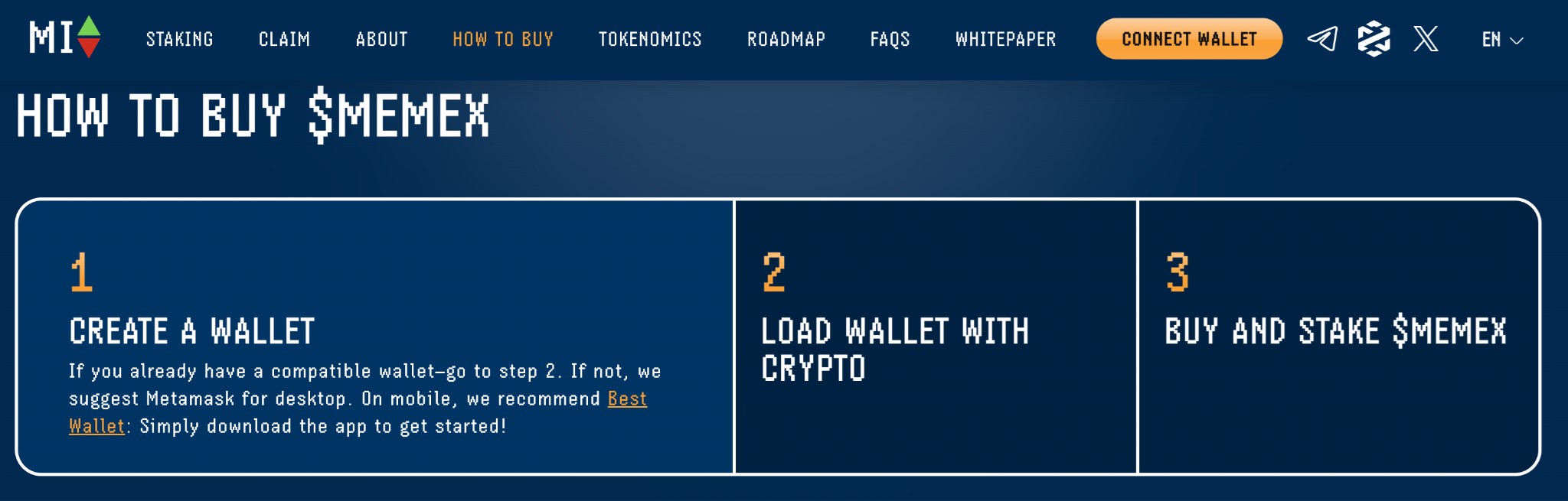

Like most Finixio team projects it shills Best Wallet:

Every place it can:

https://memeindex.com/#how-to-buy

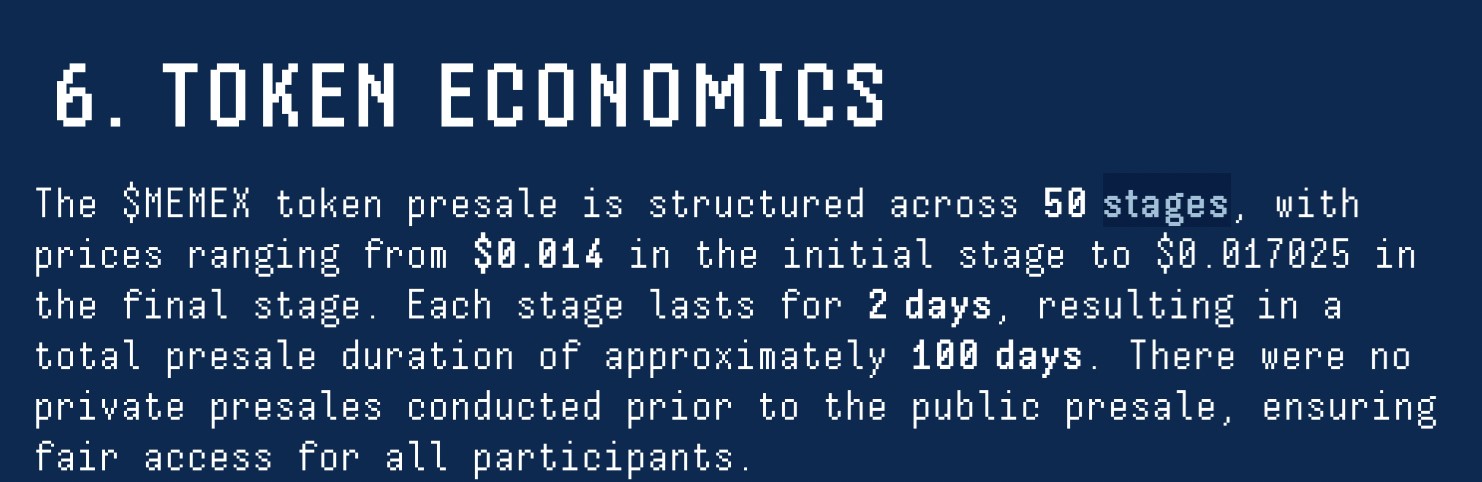

And like most Finixio team projects it ran an extensive presale, starting in January this year:

https://web.archive.org/web/20250103210230/https://memeindex.com/

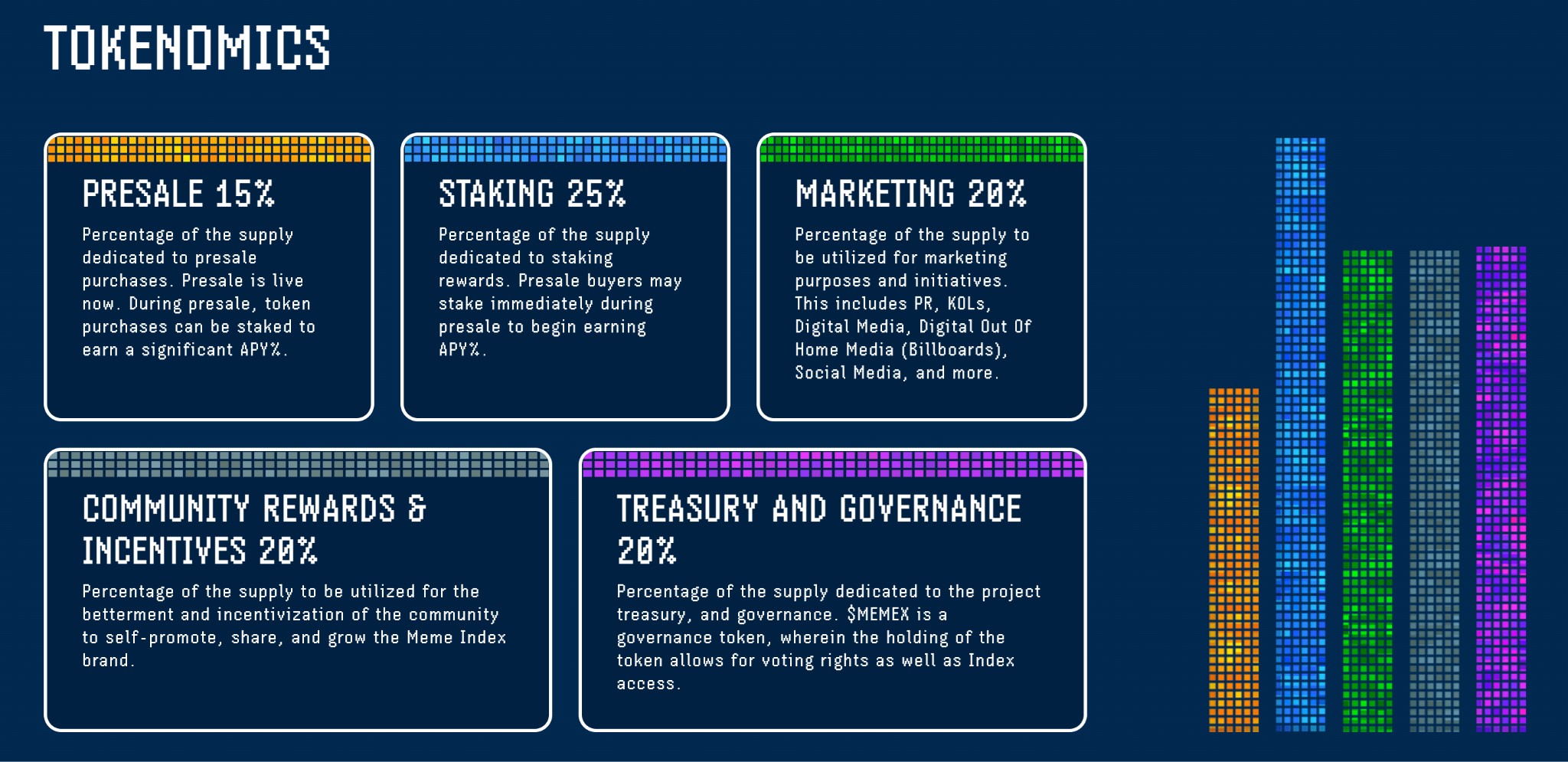

Its tokenomics section on its website made claims about the percentages of tokens that would be ascribed to each use:

https://memeindex.com/#tokenomics

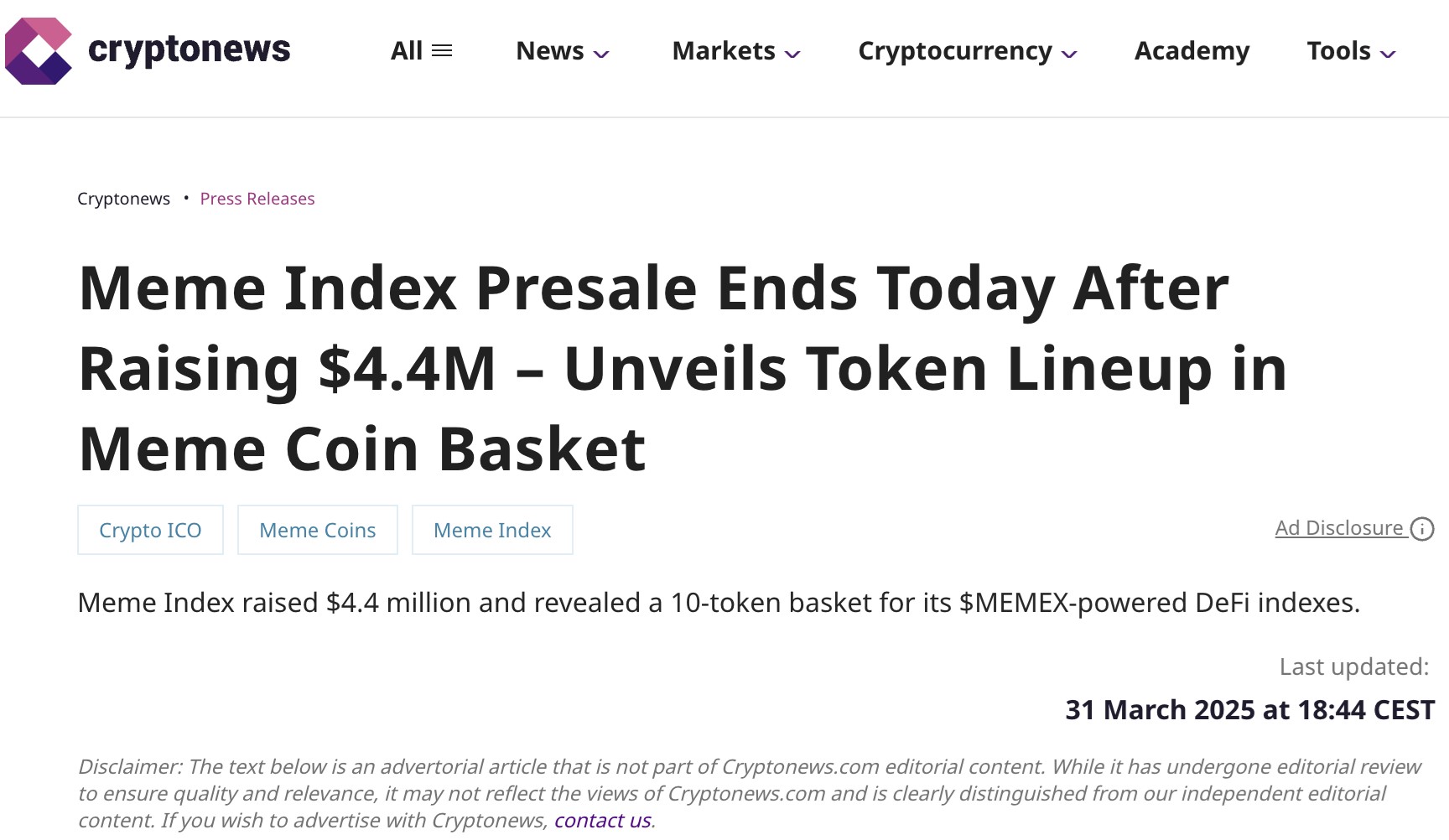

Like most Finixio products it was enthusiastically promoted through the group’s marketing assets, though with some disclaimers.

https://cryptonews.com/press-releases/meme-index-presale-ends-after-raising-4-4-in-memex-sale/

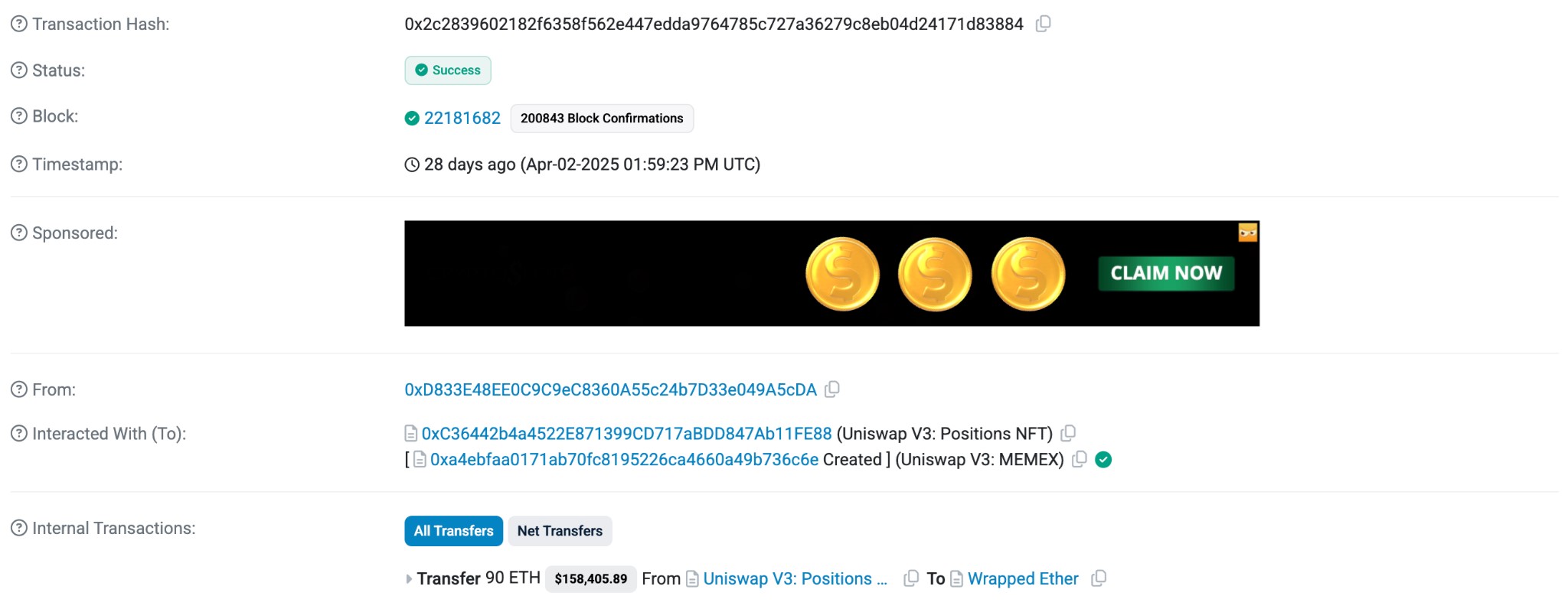

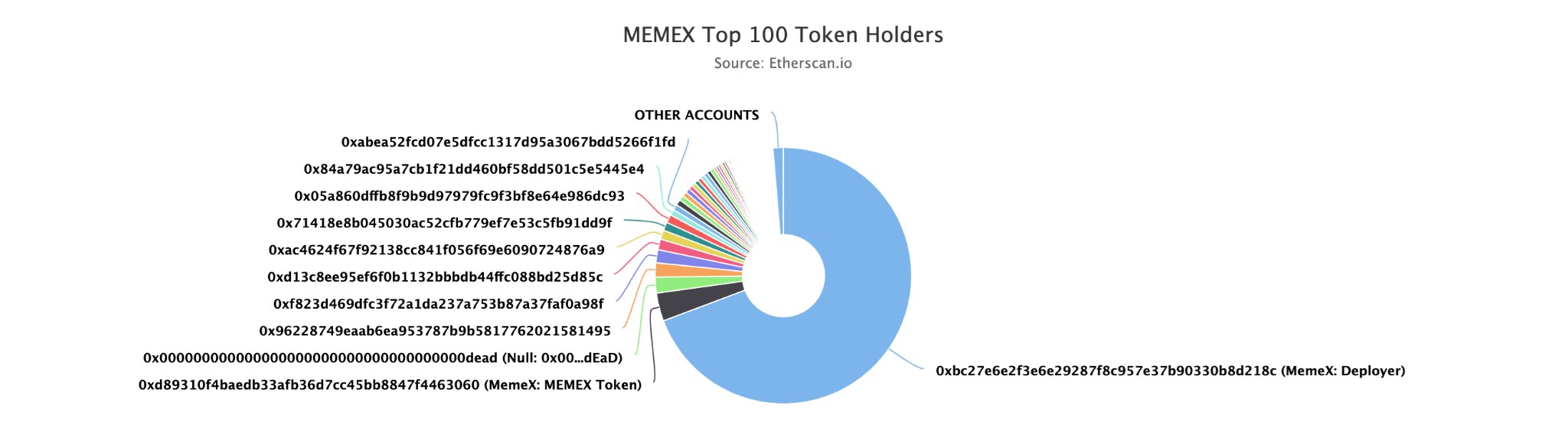

When the project went live, things continued to be familiar. First, the assigned liquidity pool was extremely small, at just 3.7% of tokens:

That’s an unusually small liquidity pool. It’s similar in size, percentage-wise, to the one used by Wall Street Pepe previously. (Again, Wall Street Pepe is an unusual case we’ll be looking at closely and in isolation further down.)

And there’s one other way the presale is familiar.

Its disastrous price performance.

In fact, if you look closely you can see it started out at 0.016USD, which is concerning — not least for the investors in the final stage of the presale:

https://memeindex.com/assets/documents/whitepaper.pdf

Because those investors paid more for this token than the price it went on sale at on day one.

Everyone who bought this token in the presale paid more for it than it has been worth since 6 PM on the day it was launched.

The contract for the token currently holds 69% of all extant tokens, a supply of 100,000,000 tokens:

That’s in contrast to the 15,000,000,000 tokens the project’s white paper proposed.

Since its launch, the price of the MEMEX token has fallen by 92%, a near-total loss that leaves investors holding just eight cents on the dollar.

These numbers aren’t unusual for a Finixio team-controlled project, and in some projects they’re even more egregious.

The company owns casinos, but a presale isn’t meant to be a gamble. There’s risk, but it’s not supposed to be a game of chance. Presales rely on trust, based on accurate representation of the numbers and the facts of the project.

This doesn’t look like that’s happening.

It looks like a conveyor belt of Ponzi schemes.

We can find a similar picture in a couple of the Finixio team’s older projects, including Fightout, Tamadoge, and Love Hate INU.

FightOut, Love Hate INU, and Tamadoge: tracing the flow of finances on the blockchain in historical Finixio projects

(We had some help from a professional on tracking crypto transactions for these projects. Thanks, Darren Jackson of CrypTegridy!)

We’ll start with the projects, then delve into the blockchain and show where some of the funds went.

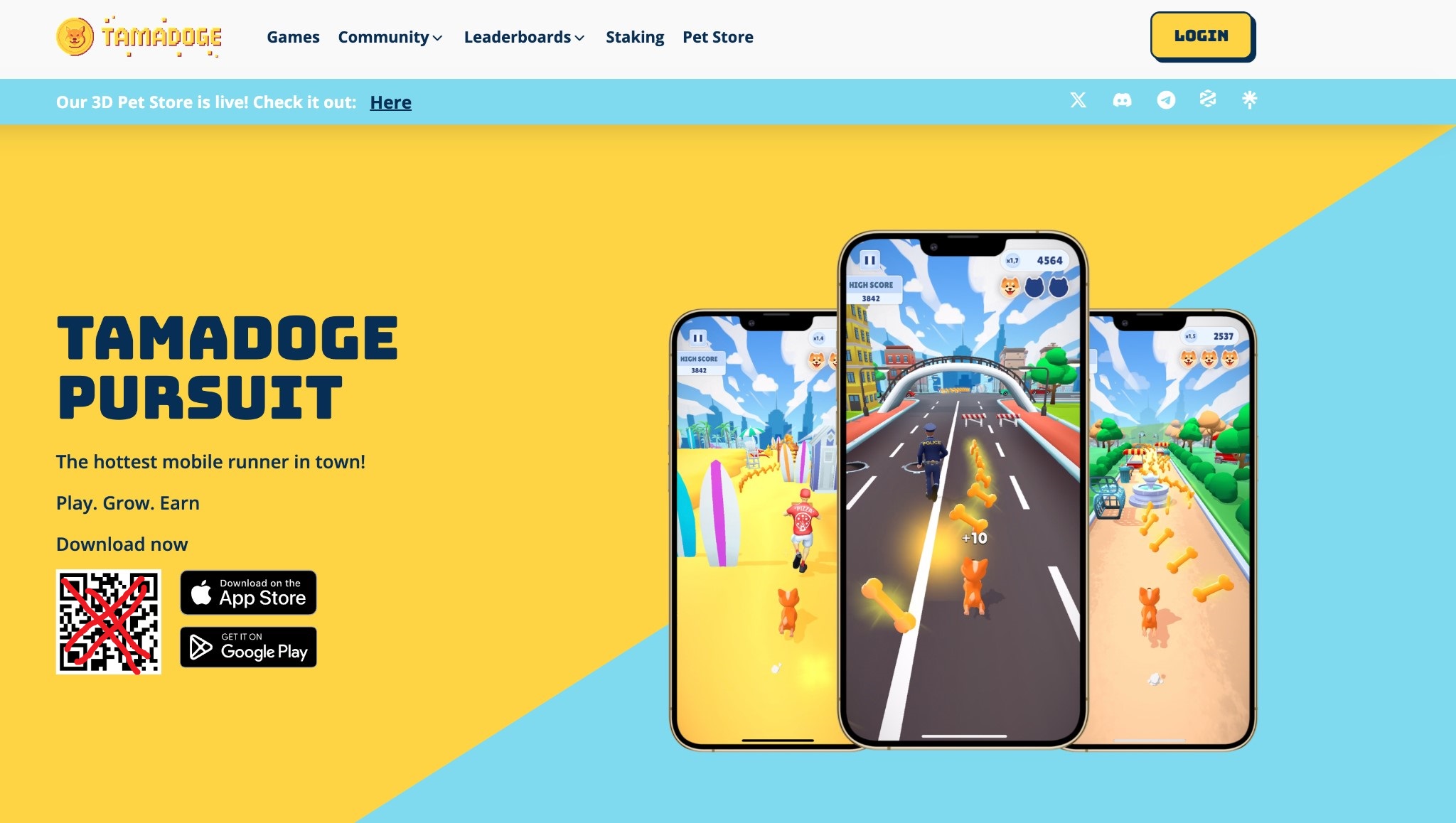

Tamadoge is a major Finixio project:

I thought I might have some trouble linking them at first. But I have that recruiter’s email, which I’ll show again:

They openly state that they own it.

(Of course, I also have the official ownership records, but you’ll have to wait for part five for those…)

It’s a virtual pet store and platform that’s free to play and where users can earn tokens by caring for their pets; the name echoes both the ‘doge’ meme and the virtual-pet Tamagotchi craze. The Twitter channel is still live-ish, but hasn’t posted since September of last year. The project launched in September 2022. In case you’re not bored of looking at graphs like this by now, here’s its price history:

https://www.coingecko.com/en/coins/tamadoge

That is a lot of red.

Next, Love Hate INU.

They don’t even have a website yet, it’s still ‘under construction,’ at a URL that returns a security alert: https://www.lovehateinu.com/en. There’s a website to claim tokens you’ve bought (https://claim.lovehateinu.com/) but that also returns a security alert.

There’s a Twitter but it’s been inactive since October 2024. There’s a Youtube channel but it’s empty.

https://www.coinbase.com/en-gb/price/love-hate-inu

There’s that graph again. (I swear these are different, I’m not just putting the same one in over and over. They just all look the same, for some reason.)

Finally, Fightout.

FightOut is a mix of fighting game and betting platform, with a virtual MMA game and gambling on the real UFC.

The game and the betting platform interact with each other.

It’s quite sophisticated compared with some of the memecoins we’ve looked at so far.

Some of these look familiar though.

Fightout is a one-page site without even a link to the project’s white paper available. But it does have a blog, not visible in the site’s navigation but hosted on its domain.

Google link

Google link

I can’t tell if that’s good advice about web design or not, but it does seem pretty tangential to the site’s purpose.

The whitepaper is available on the Wayback Machine, though. Look who it’s backed by:

https://web.archive.org/web/20230325122736/https://whitepaper.fightout.com/

It looks like the game isn’t on Google Play anymore, and the Youtube channel isn’t active anymore either.

Here’s its price history:

This isn’t so great.

But what’s more interesting is the on-chain activities associated with this project — and the others mentioned here. I’d love to do them project by project, I feel like that would be simpler, but unfortunately it would also be impossible, for much the same reason that it’s hard to walk on one foot, or pick up one end of a snake. One or two levels down, these are essentially the same project.

Let’s get into the blockchain activity for these projects, once again with thanks to blockchain consultant and our expert source, Darren Jackson.

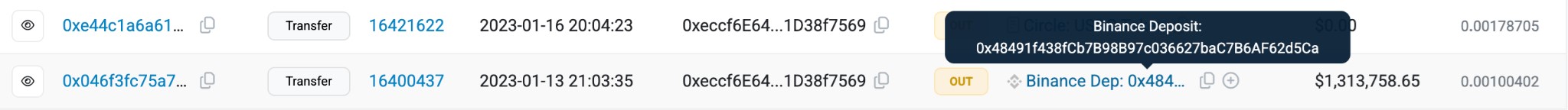

We’ll start with Tamadoge

An exchange address was used to fund the Tamadoge smart contract deployer. Darren explained to us that money in the form of crypto moved through multiple wallets, including the contract creator address 0x56D9e4a0663ea4Fa310887c1ee02a56824C4533b, to the Lucky Block contract deployer, 0xD392DdB57211CeD5a5074Ec6311D0af10ff0017B.

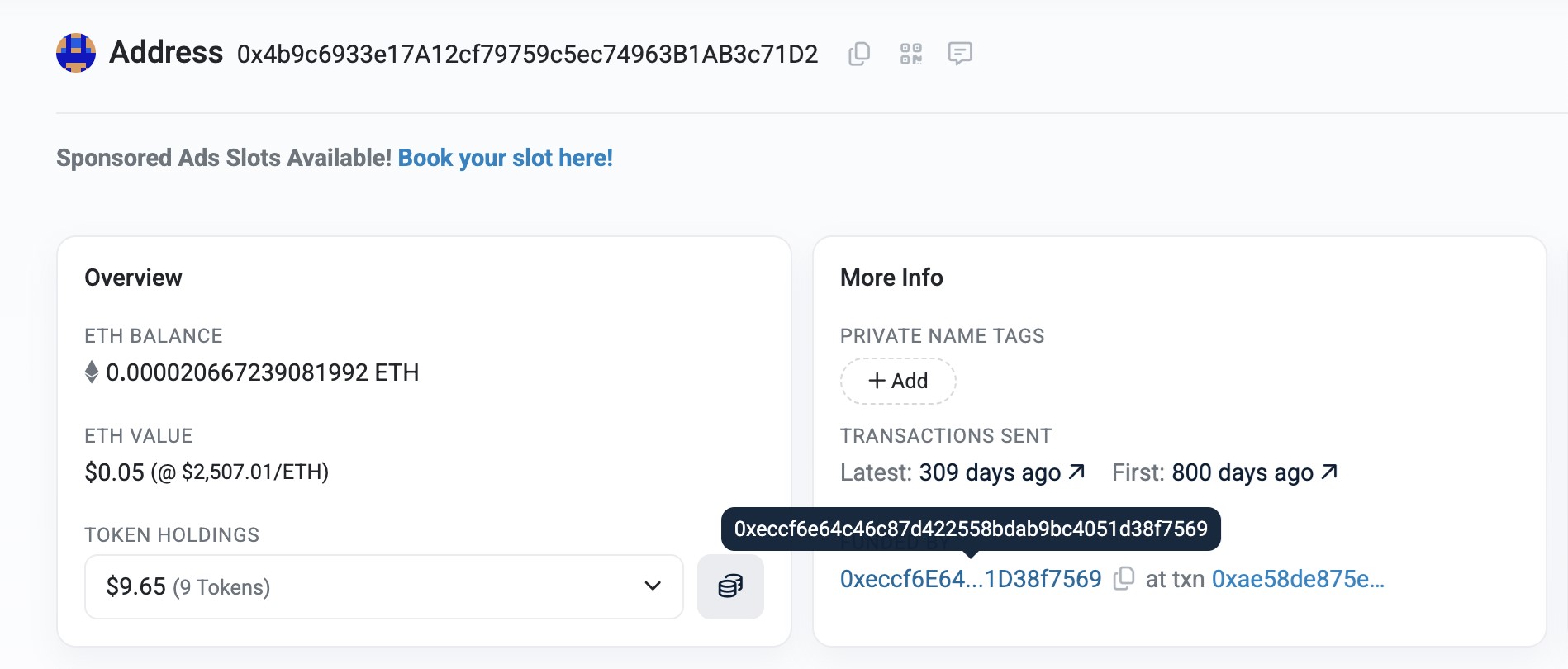

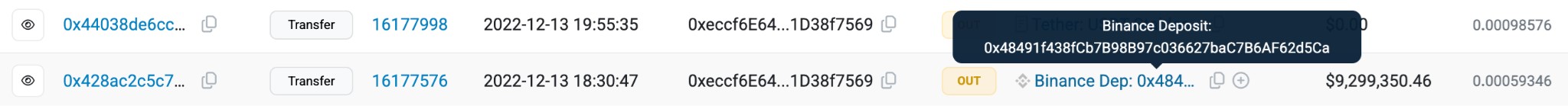

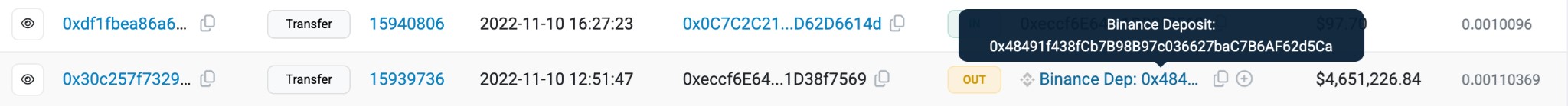

Darren further told us that the ultimate beneficial receiver of the presale assets from Tamadoge, totalling $19 million, was the wallet 0xeccf6E64c46c87d422558bdAB9bC4051D38f7569, the FightOut smart contract deployer, which then forwarded those assets to the address 0x48491f438fCb7B98B97c036627baC7B6AF62d5Ca.

This last address is a Binance deposit account. Funds sent here are being sent to a centralized exchange (one with a business entity operating it).

I always find it easier to remember these addresses by the last few characters, so in my mind this is d5Ca, but a lot of people use the first few characters and remember this as 0x4849. Whichever you use, just keep these addresses in mind:

0xeccf6E64c46c87d422558bdAB9bC4051D38f7569, the Finixio-controlled address

0x48491f438fCb7B98B97c036627baC7B6AF62d5Ca, the Binance deposit account

We’ll meet them again.

The Love Hate INU contract deployer address, 0x4b9c6933e17A12cf79759c5ec74963B1AB3c71D2, is funded by the wallet address 0xeccf6E64c46c87d422558bdAB9bC4051D38f7569:

From here, crypto flowed to the deposit address at Binance.com: 0x48491f438fCb7B98B97c036627baC7B6AF62d5Ca

Good old d5Ca. Good old f7569. Told you you’d want to remember them.

Our source informs us that Love Hate INU has transferred over $2 million to this address.

But in Fightout, something different is going on.

The money came in here — and it’s going right back out again to the same place it came from.

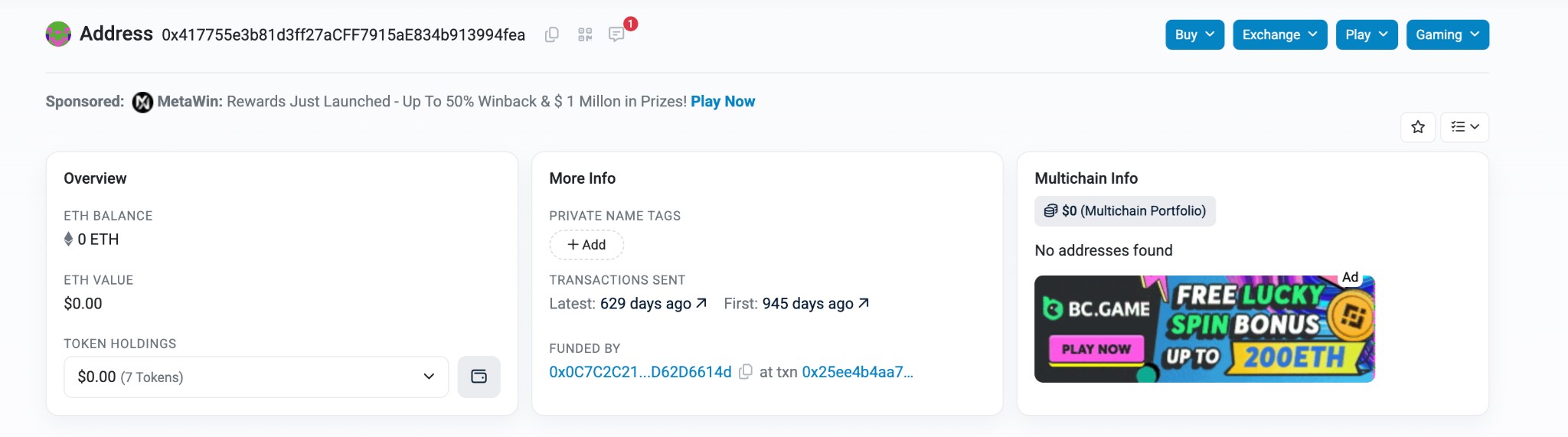

If we follow the funding, we find that the funding address is in turn funded by…

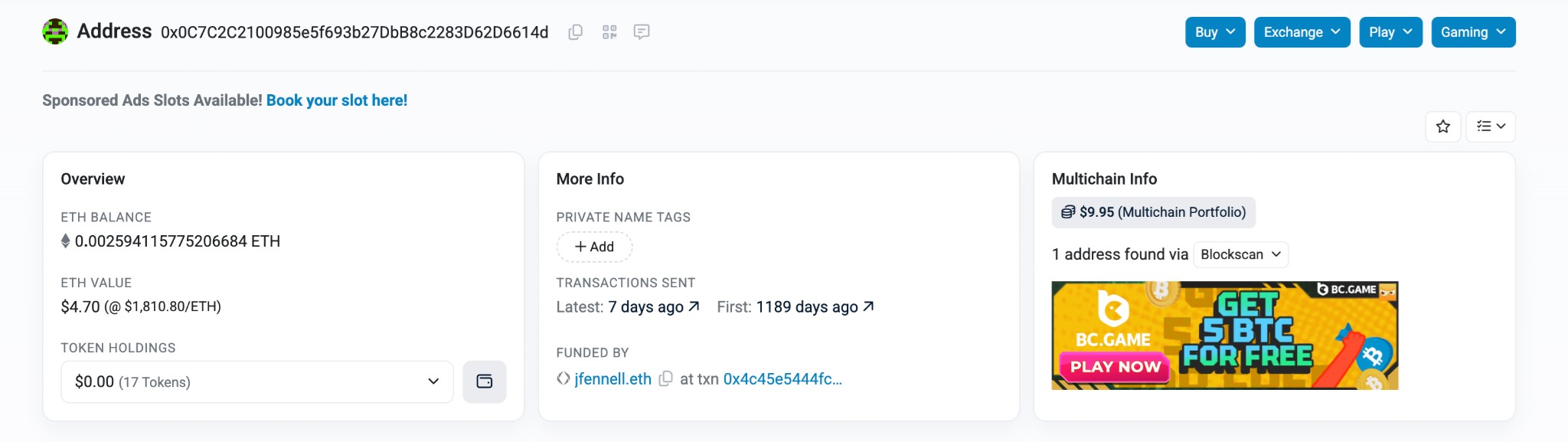

That address, by the way, is 0x0C7C2C2100985e5f693b27DbB8c2283D62D6614d.

Which is in turn funded by…

jfennel.eth.

The Ethereum blockchain address of James Fennel, key member of several Finixio projects, longtime associate of Adam Grunwerg and Samuel Miranda, and as we’ll see, one of the chosen few Finixio staff who own the real money-making assets. (To see the official receipts on that, keep an eye out for episode 5 of this series.)

Time to look more closely at 0xeccf6E64c46c87d422558bdAB9bC4051D38f7569.

This address has been identified by our expert source as ‘almost certainly controlled by the Finixio team’ and he referred to it throughout our conversation as ‘the Finixio team-controlled address.’

Take things back a step.

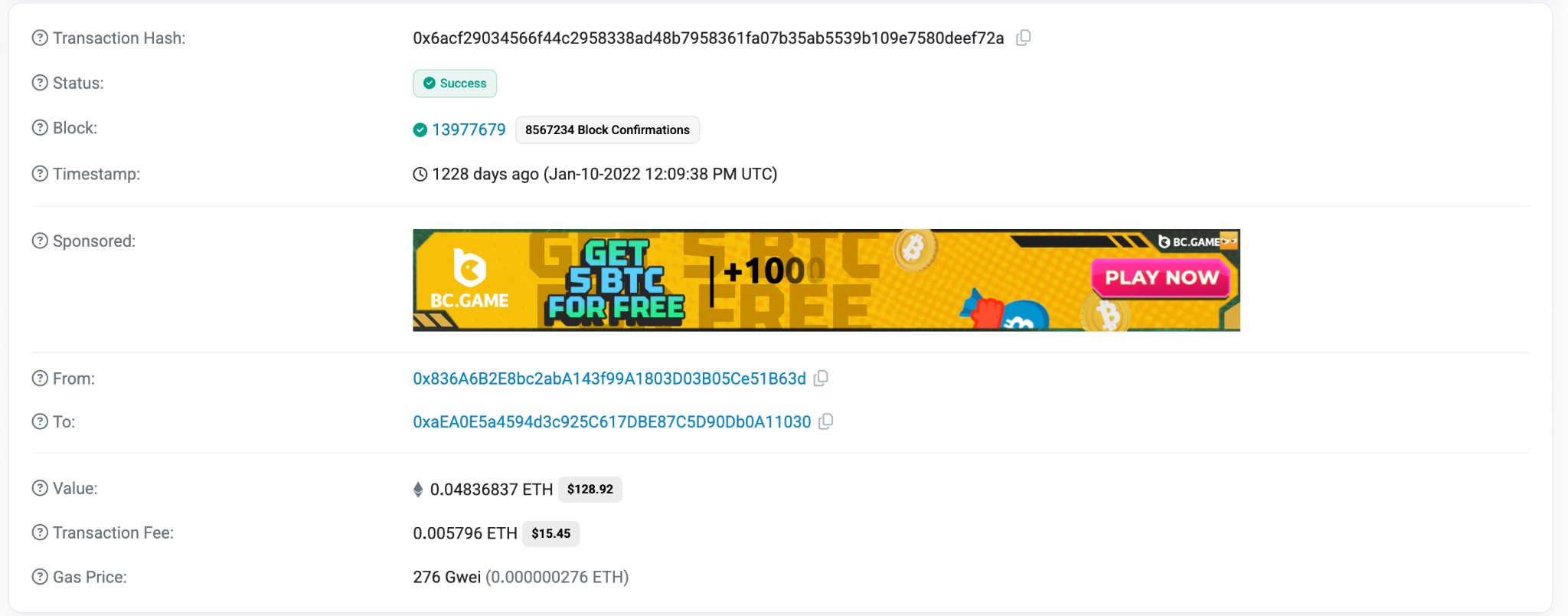

Here’s the genesis transaction:

That’s address 0xC88F7666330b4b511358b7742dC2a3234710e7B1 funding address

0x836A6B2E8bc2abA143f99A1803D03B05Ce51B63d. That address went on to fund 0xeccf6E64c46c87d422558bdAB9bC4051D38f7569, which we’ve met before.

All these projects ultimately funnel their proceeds back to just a few wallet addresses, like …f7569 and ultimately to …d5Ca.

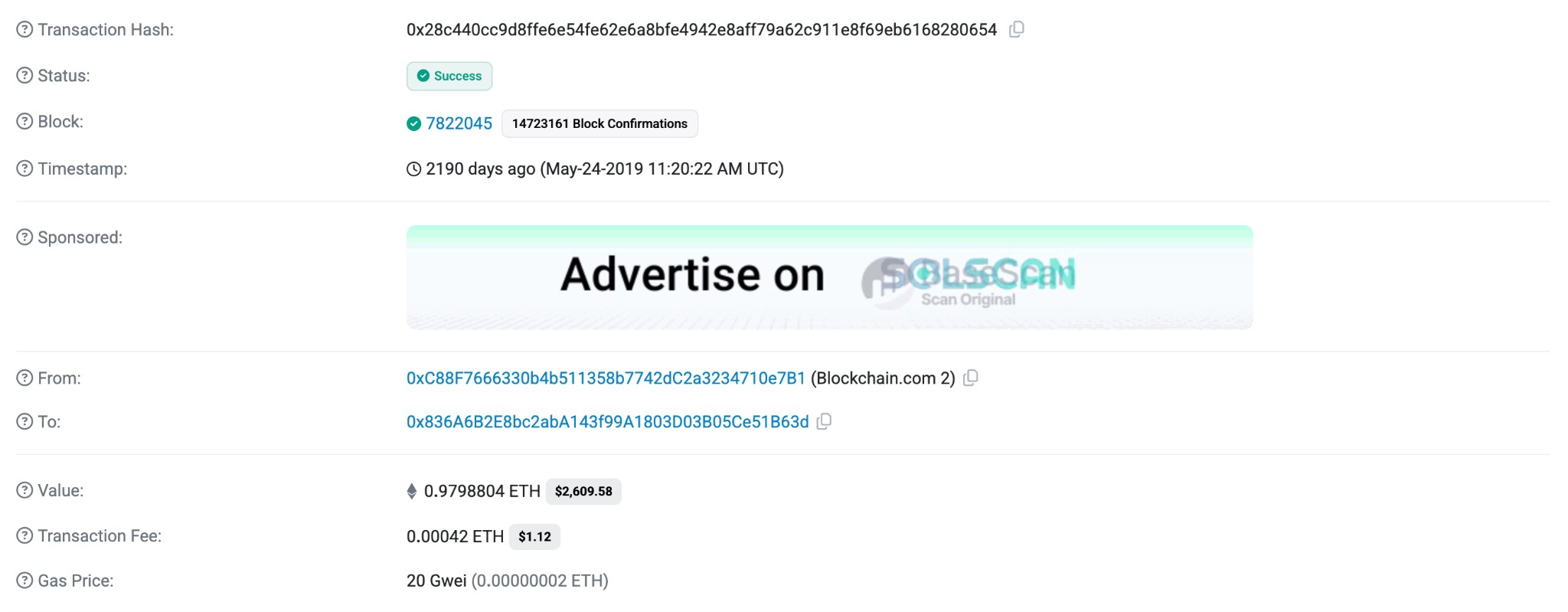

And here are some of the withdrawals from 0xeccf6E64c46c87d422558bdAB9bC4051D38f7569 to 0x48491f438fCb7B98B97c036627baC7B6AF62d5Ca:

$1.3 million, on January 13, 2023.

Nearly 10 million a month earlier to the day.

$4.6 million the previous month.

These are serious sums, all coming out of the funnel here.

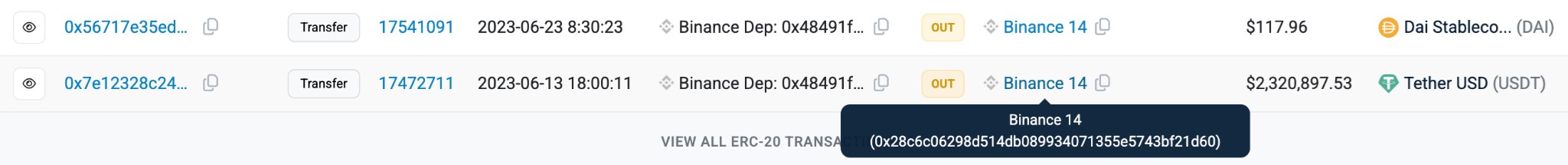

Hundreds of thousands and millions come in denominated in stablecoin currencies like Tether (a cryptocurrency pegged to the value of the US dollar).

Where do they go?

Out, to this Binance address:

0x28C6c06298d514Db089934071355E5743bf21d60

In staggering sums:

This is a process called ‘sweeping,’ in which an exchange like Binance regularly ‘sweeps’ all deposit addresses into one address.

The way that works can be a little surprising for non-blockchain people. Here’s what’s happening.

When you move crypto to a centralized exchange, like Binance, the money stays yours. But for the purposes of blockchain records, all that money becomes Binance’s, along with everyone else’s. You’re mixing it all together, a process unsurprisingly known as ‘mixing,’ and if you’re trying to obfuscate the origin, value, or destination of funds it’s a very useful thing to be able to do. Centralized crypto exchanges make it near-impossible to follow money through them: once your funds go into an exchange like this their history is gone.

If the pattern holds good, you’d expect to see similar price curves in other Finixio projects.

According to Crypto Rug Muncher on Twitter/X, this is a list of upcoming Finixio projects:

https://x.com/CryptoRugMunch/status/1886805232878858528

https://x.com/CryptoRugMunch/status/1886805232878858528

…as of February 2025. Notice that presales have raised tens of millions of dollars across these projects.

To recap, there’s money coming in and out of these projects in significant sums, being converted from low-value tokens to stablecoins (like Tether) and then vanishing onto exchanges.

In some cases, the money cycles between wallets owned by the project operators, and wallets owned by the project, several times first — a process indicative of ‘pumping’ the price. We’ll be able to show that in episode 4, as well as answering the question:

Are they all going to be emptied out right after the token goes live, the way MEMEX, Tamadoge, Fightout, and Love Hate INU were?

And… where’s all the money?

Stay tuned. We can answer some of these questions definitively.

Latest episode

Previous episodes

Part 1: Under the surface: A first look at the murky world of online gambling, crypto casinos, and memecoins

Part 2: How the crypto, gambling, and marketing networks interweave: the case of 99Bitcoins