You’ll remember that we’d established that the Finixio team owned or operated a huge number of parasite SEO websites. But we had some difficulties showing direct connections in some cases. And it was always in doubt — how involved are these individuals? After all, there’s ‘beneficial owners’ and then there’s people who show up to the work site every day dispensing orders. Are the core Finixio team boots on the ground or are they insulated from the day to day?

Listen to the full story

Read an 800 word summary courtesy of ChatGPT.com.

And you’ll remember too that we’re all about the receipts around here.

So with thanks to a source who has asked to remain anonymous, here is the proof that we weren’t able to show you before. The proof that Finixio and Clickout are so deeply involved with the projects of their parasite network that they use the same SEO and project management tools for all of them. Proof that they directly operate the main parts of the network — not just own the key assets, as we’ve previously demonstrated.

After we walk through that we’ll turn our attention back to the blockchain one last time, to trace financial flows through the complex network of wallets operated by the Finixio team and show that there’s a suspicious amount of money flowing into the network from exchanges, travelling around it, then flowing right back out again.

Wait, is there another layer to the onion?

Yes, probably. But let’s start on the factory floor of the Finixio/Clickout operation. (Why am I being less careful than before to say ‘Finixio/Clickout team’? We’ll see.)

One of the best all-around SEO tools is Ahrefs. It has more reliable data than most SEO tools and you can do an incredible amount with it.

Clickout’s Ahrefs account

If you run multiple websites you can get all of them on your Ahrefs dashboard and track things like…

…everything, basically. (This is Techopedia’s Ahrefs page. Boy that traffic falls off hard huh.)

So I congratulate Scott Ryder and Adam Grunwerg on their good taste in choosing such an effective SEO tool, which we will now show you screenshots of.

Clickout projects on Ahrefs

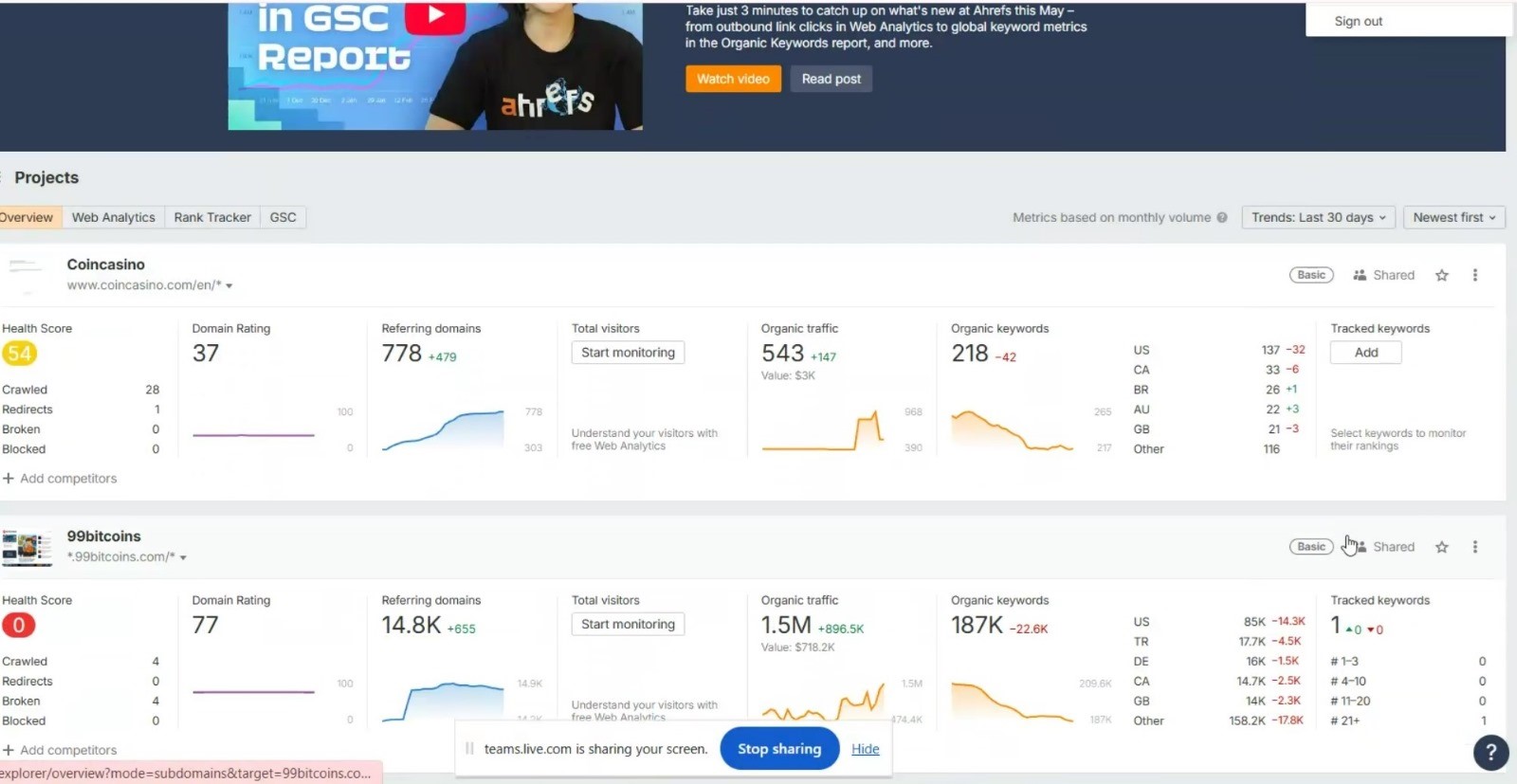

Here’s Coin Casino:

https://www.coincasino.com/en

Previously the best we could do was tie this site to its registered operator, Igloo Ventures, a black box in Costa Rica.

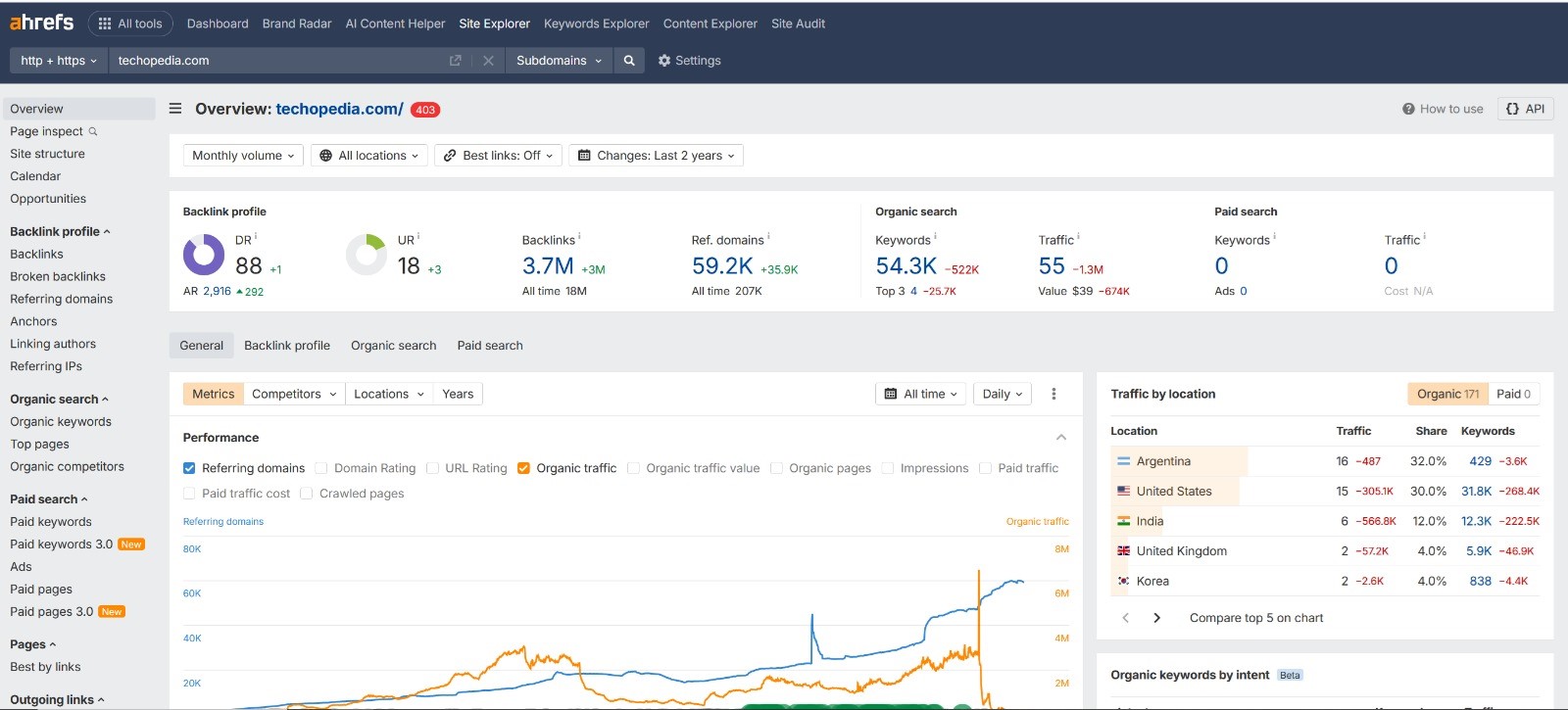

And 99 Bitcoins:

https://99bitcoins.com

We did a whole post on this outfit.

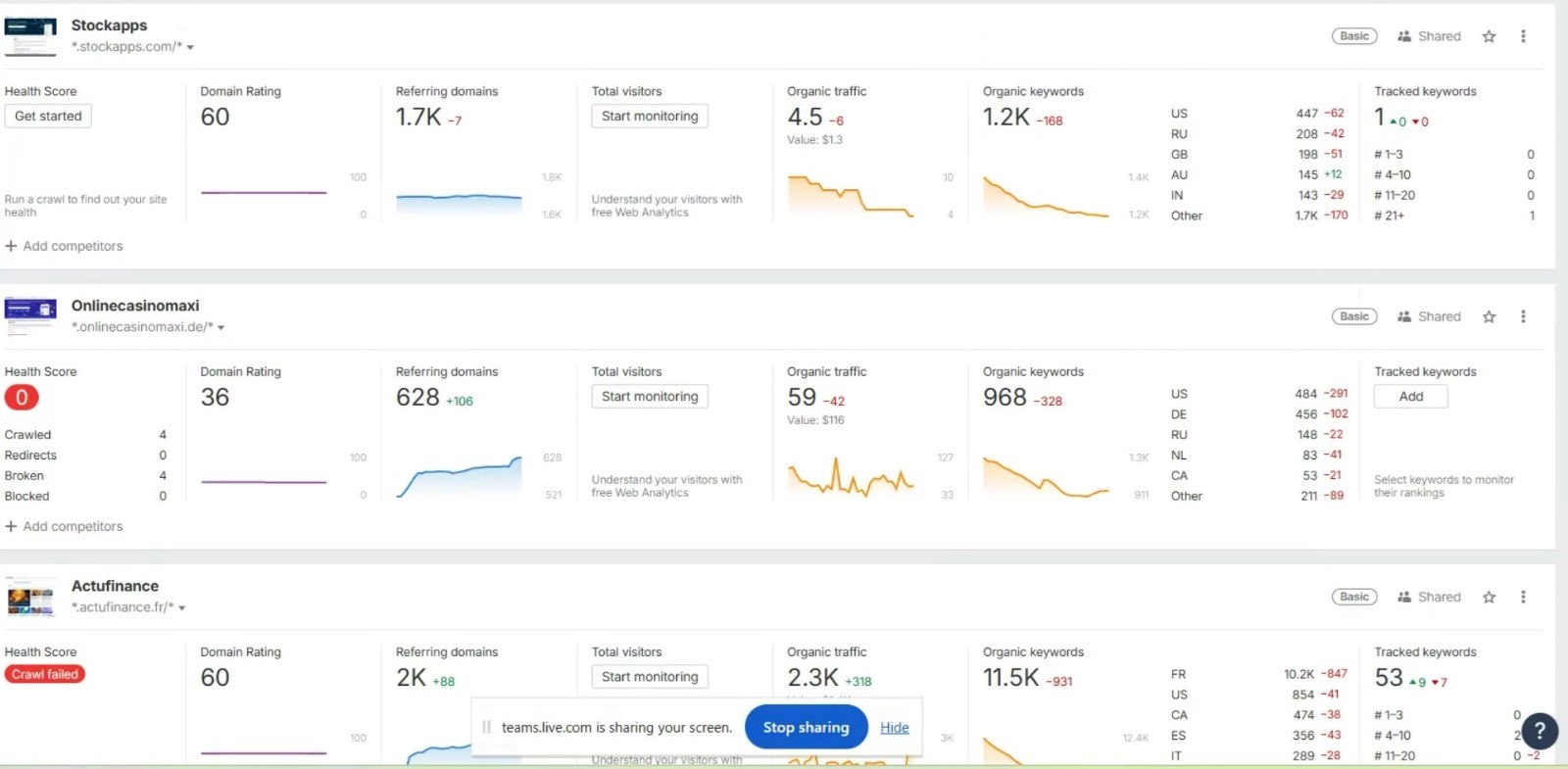

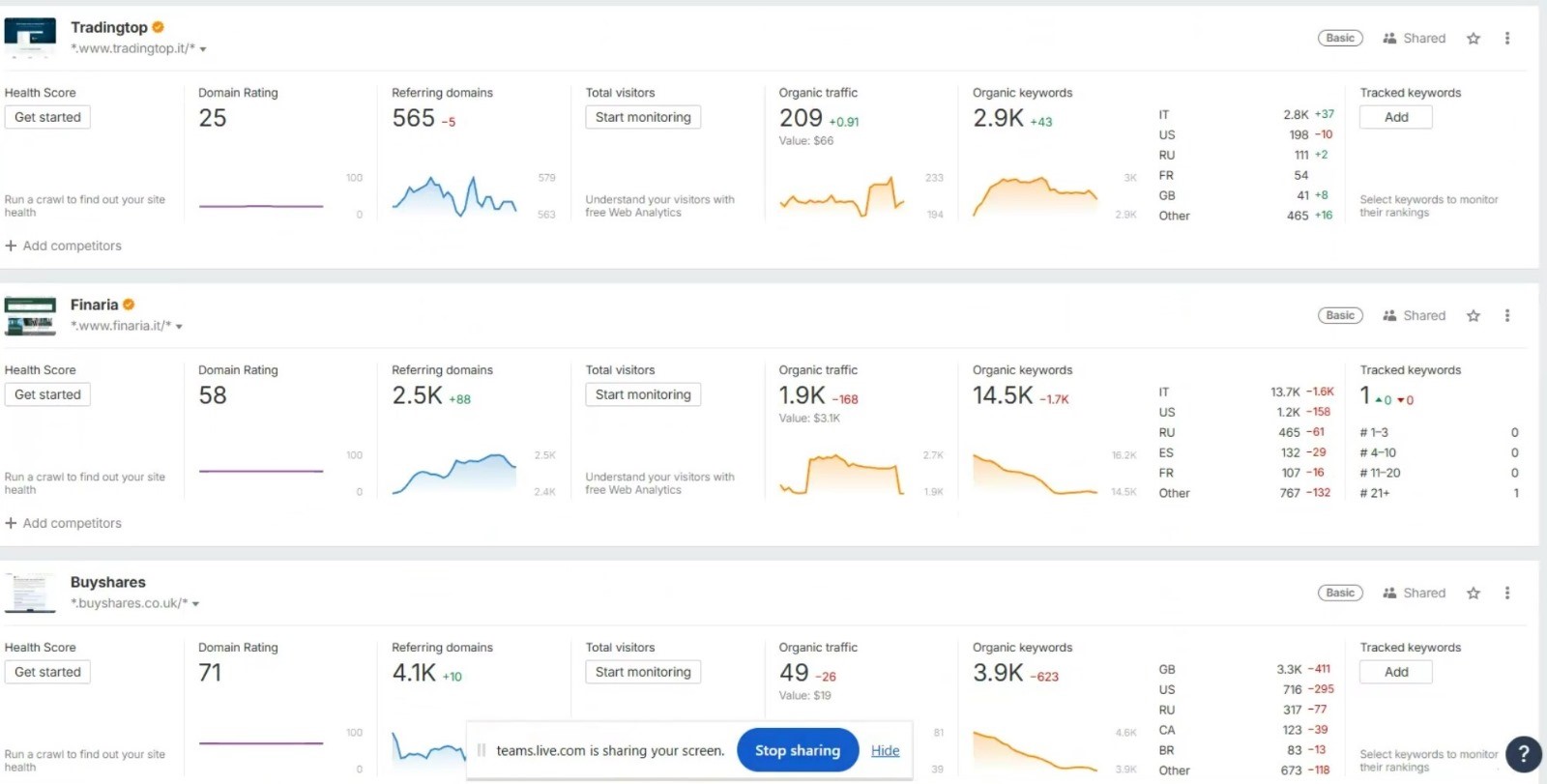

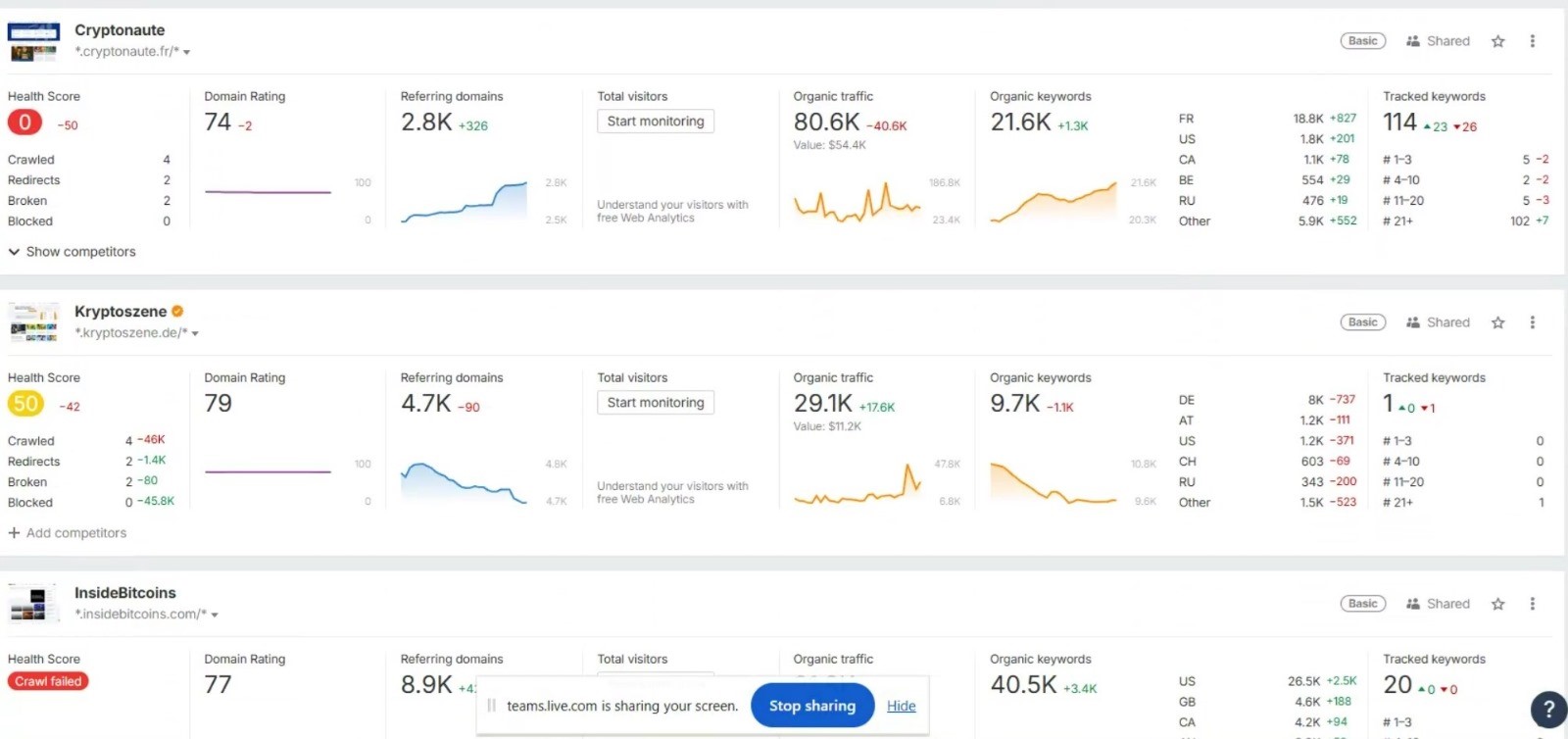

The dashboards

Anyway, here’s the Ahrefs account screenshot for both operations:

(How did we get this? I was approached by someone from the organization who felt both bad about what the company did, and mistreated by them. They agreed to supply us the material we needed to make these connections, on the grounds of total anonymity. We owe them a lot because of their willingness to come forward and give us this material that we could never have accessed otherwise.)

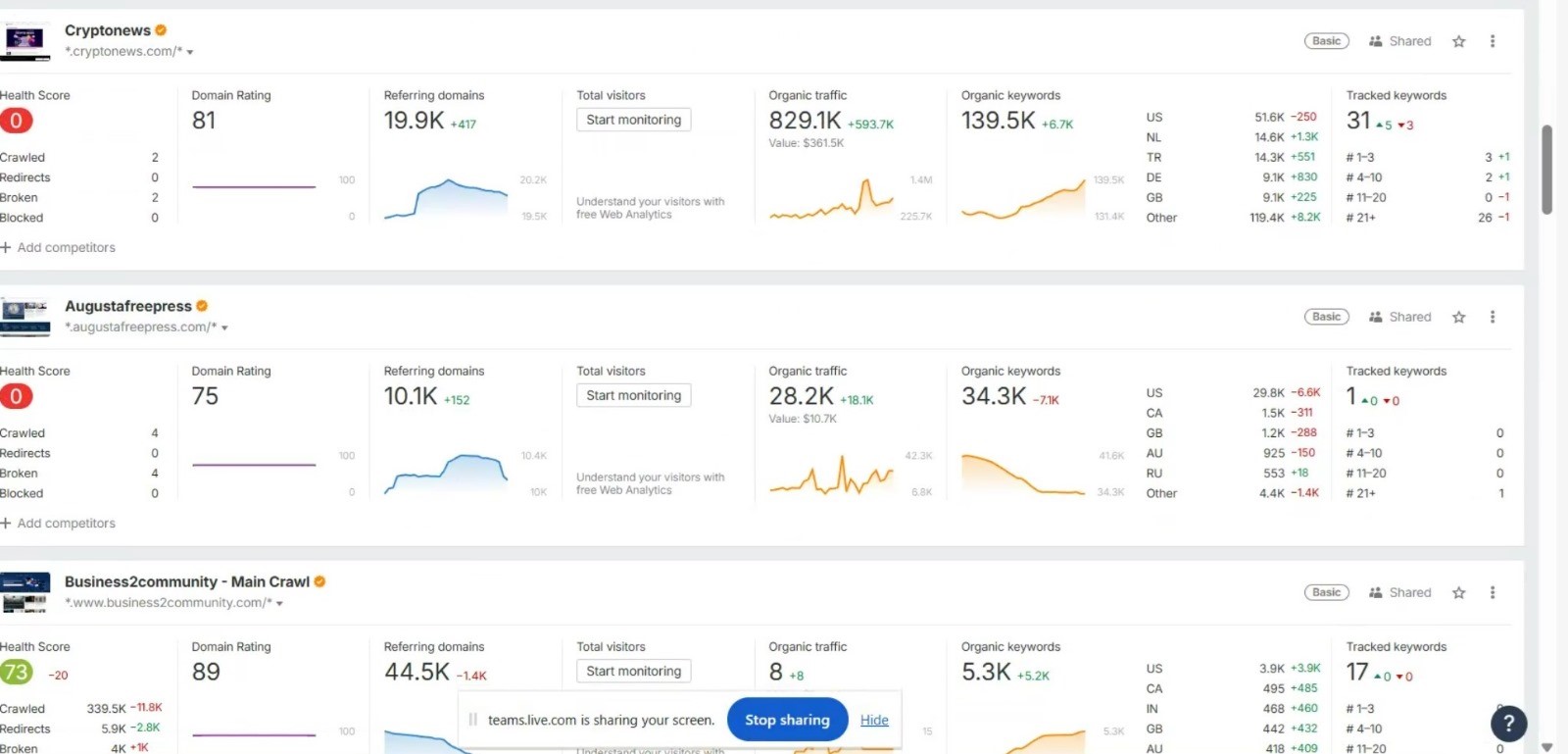

Or how about CryptoNews and Business2Community?

We knew these were Finixio team operations, and in the case of Business2Community we knew the site was owned outright by Clickout. But that’s a long way from being able to show that along with the rest of the network, it’s managed from the same SEO dashboards and, as we’ll see, group chats.

Meanwhile, maybe you remember Coincierge? Or Inside Bitcoins?

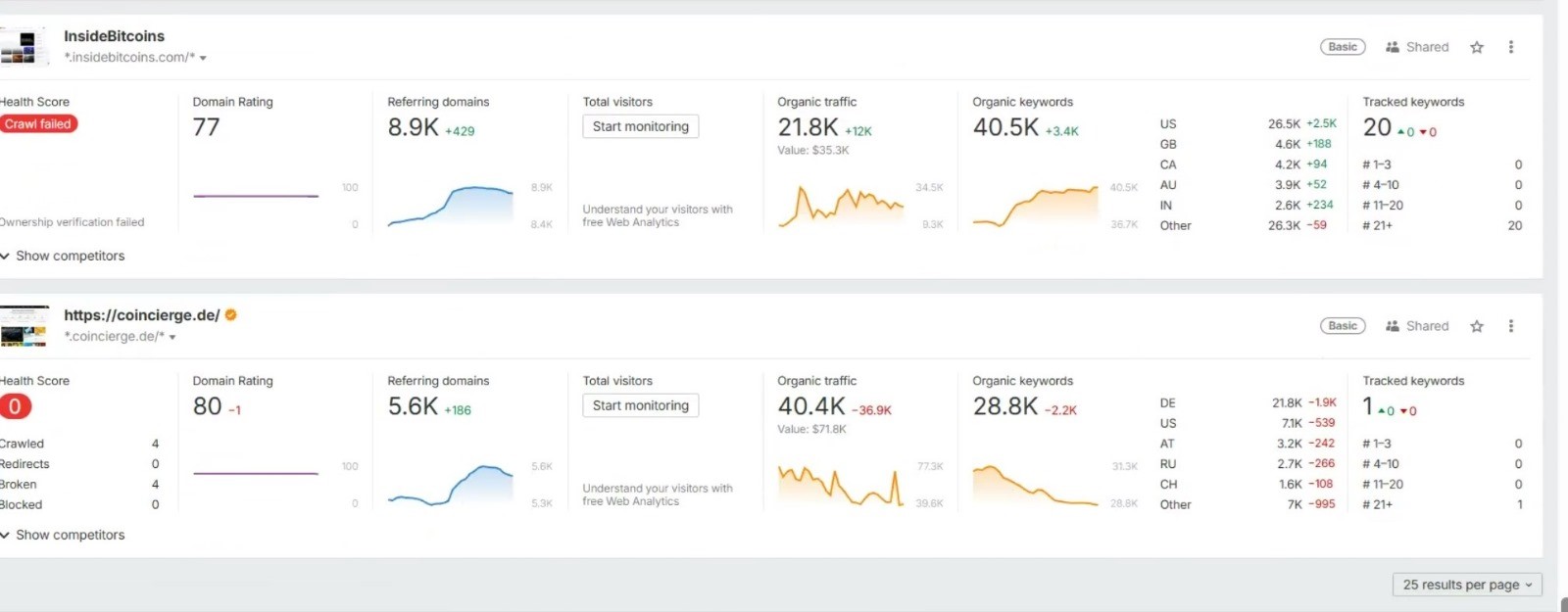

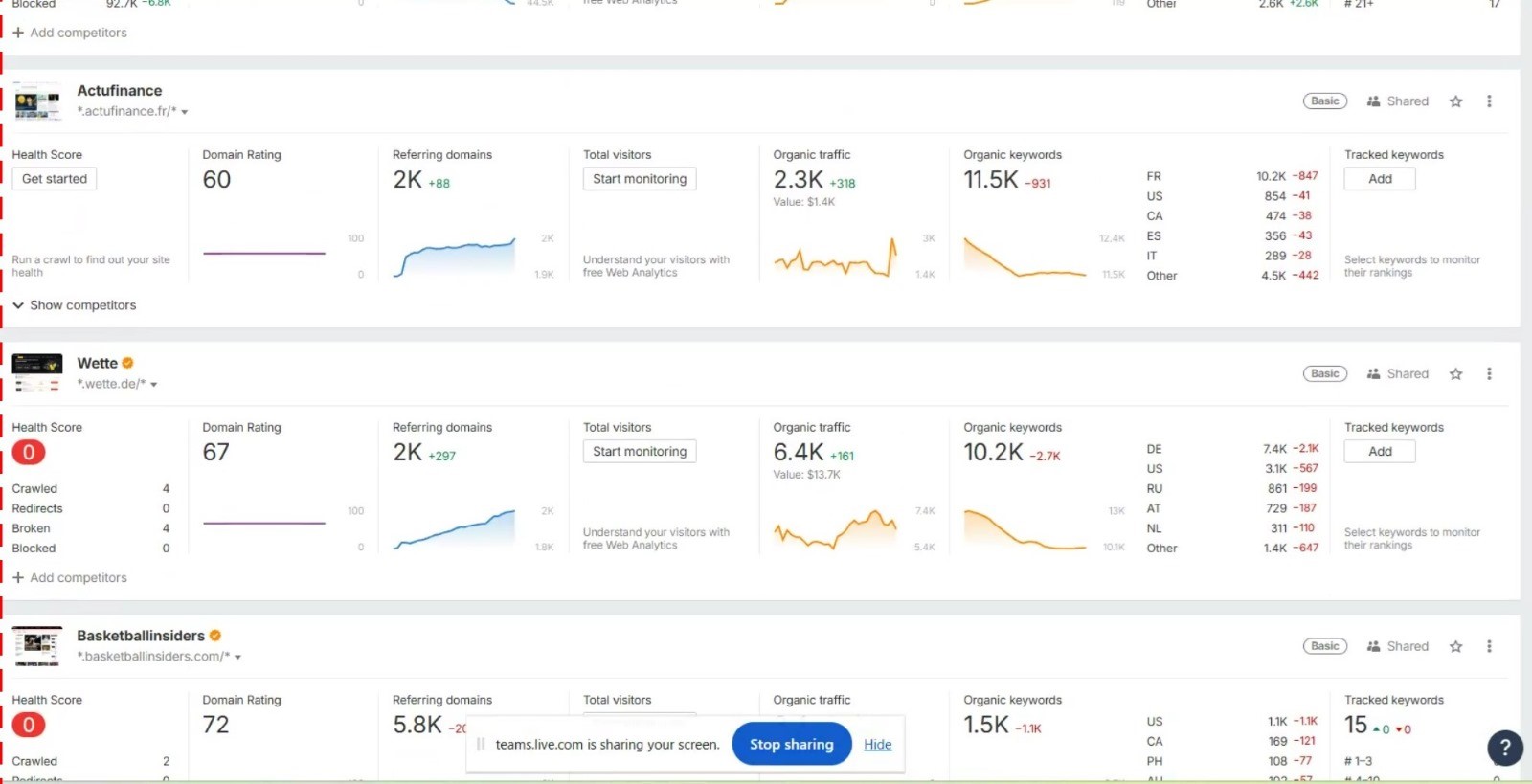

There are… more:

And more.

And more.

Scroll through the first 50 here:

It’s worth looking at the big number on the far left in all these screenshots — the Domain Rating. That tells you a lot about the function of the site in the Finixio/Clickout network. DR can be misleading, it’s a quick-and-dirty metric that doesn’t give a full picture. But with that said…

Most sites have DRs above 70, and they exist to drive traffic.

If you see a site with a DR below 60 in the list above, it’s a casino.

The network functions by pulling traffic to the high-DR sites, then sending it to the low-DR sites to make sales.

Long story short: if you’re getting your news about crypto or gambling from these sites, well, I’d stop.

But who’s behind it? How involved are the main Finixio players?

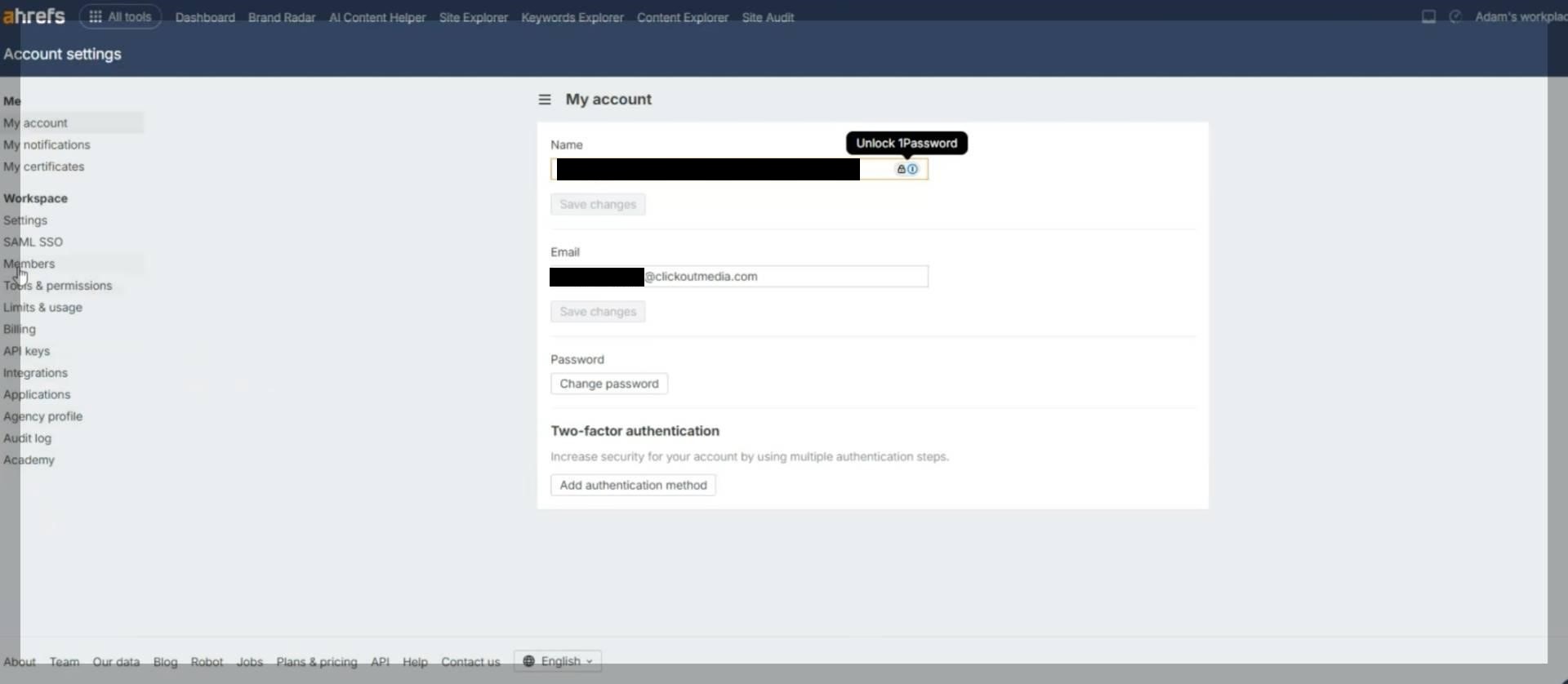

Clickout members on Ahrefs

One clue is the user name in the video above: ‘Adam’s workplace.’ That’s very likely Adam Grunwerg.

As we’ll see.

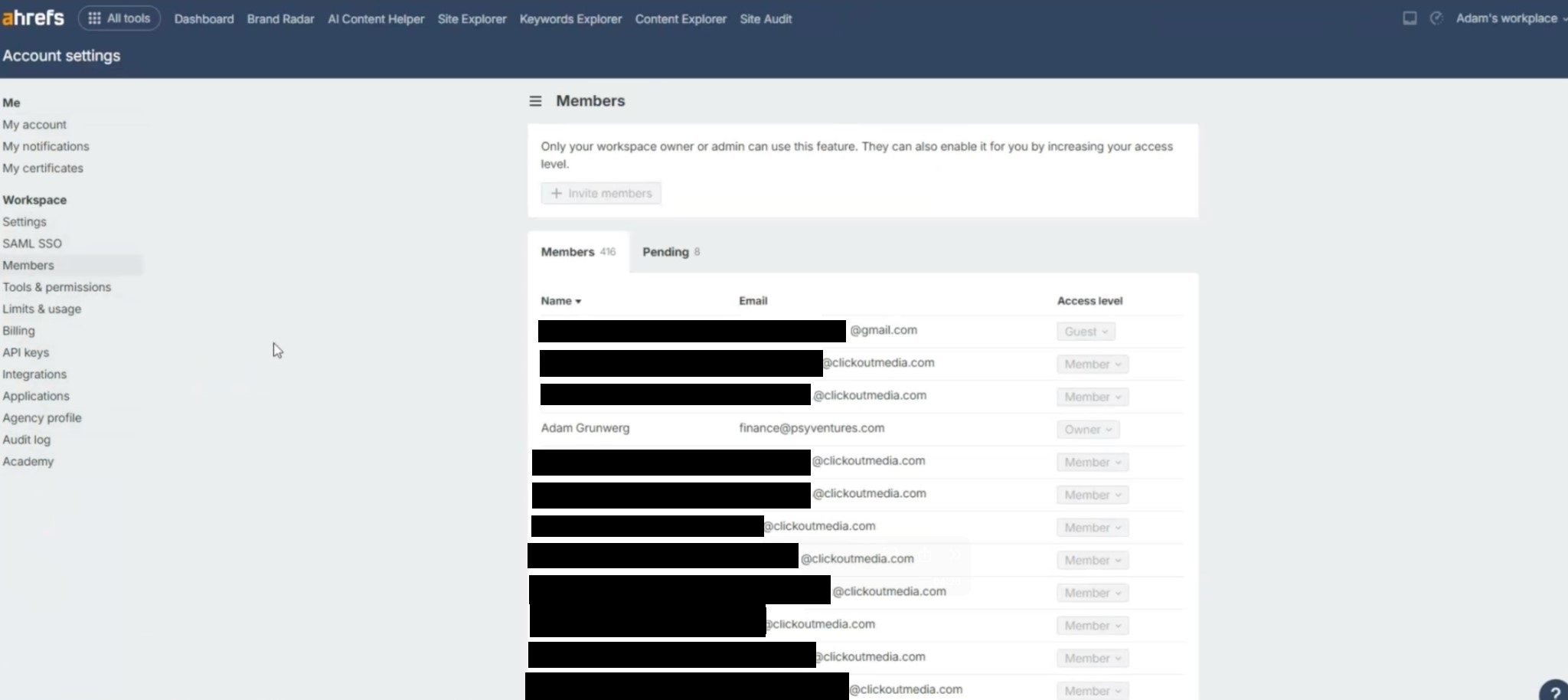

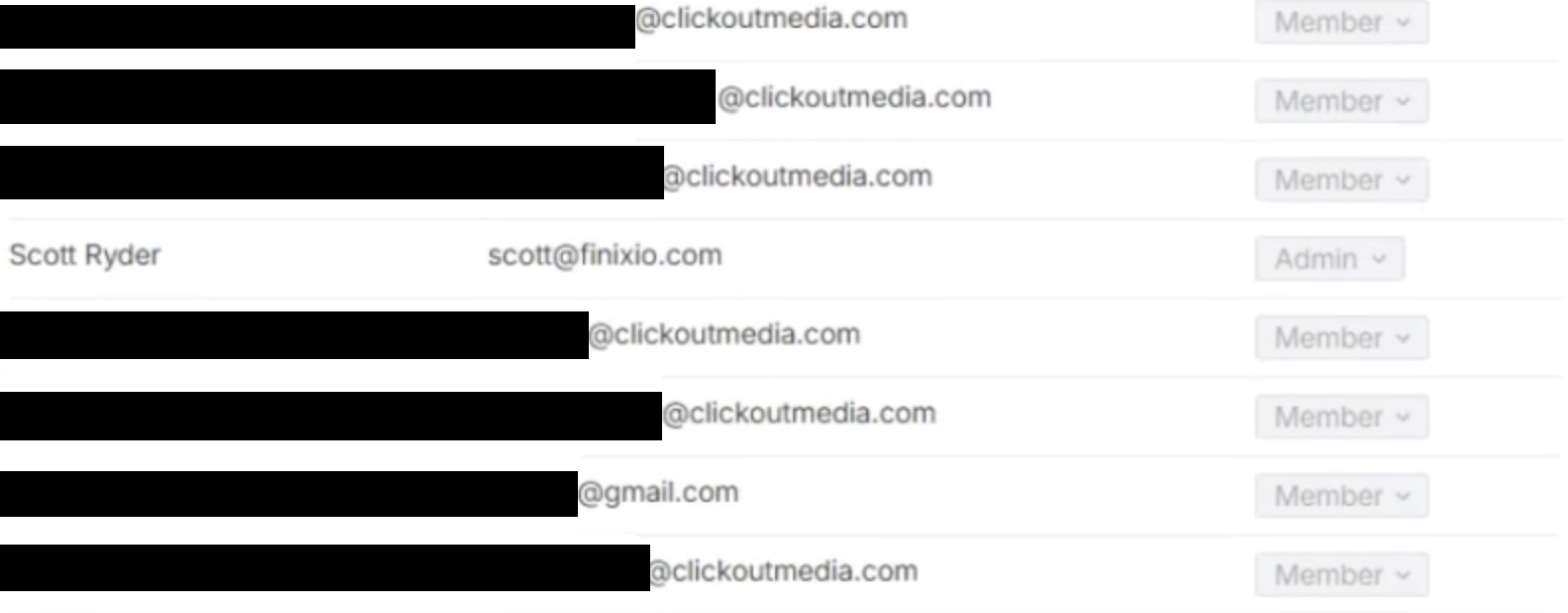

Here we are going to Members in Ahrefs. (Some user names have been redacted.)

And here are some of those members.

Names have been concealed, for the most part, but notice that almost all these URLs end in @clickoutmedia.com. Notice, too, the name I have left visible: Adam Grunwerg, at [email protected].

From further down the same list, here’s Scott Ryder, owner and CEO of Lucky Block and Finixio’s Head of Business Development. Note that in a sea of @clickoutmedia.com email addresses, his is @finixio.com.

And way down at the bottom, here’s…

…[email protected]. Given that Adam Grunwerg is [email protected], and Samuel Miranda is formerly a director at Psychic Ventures, it seems a fair bet that this is Samuel Miranda.

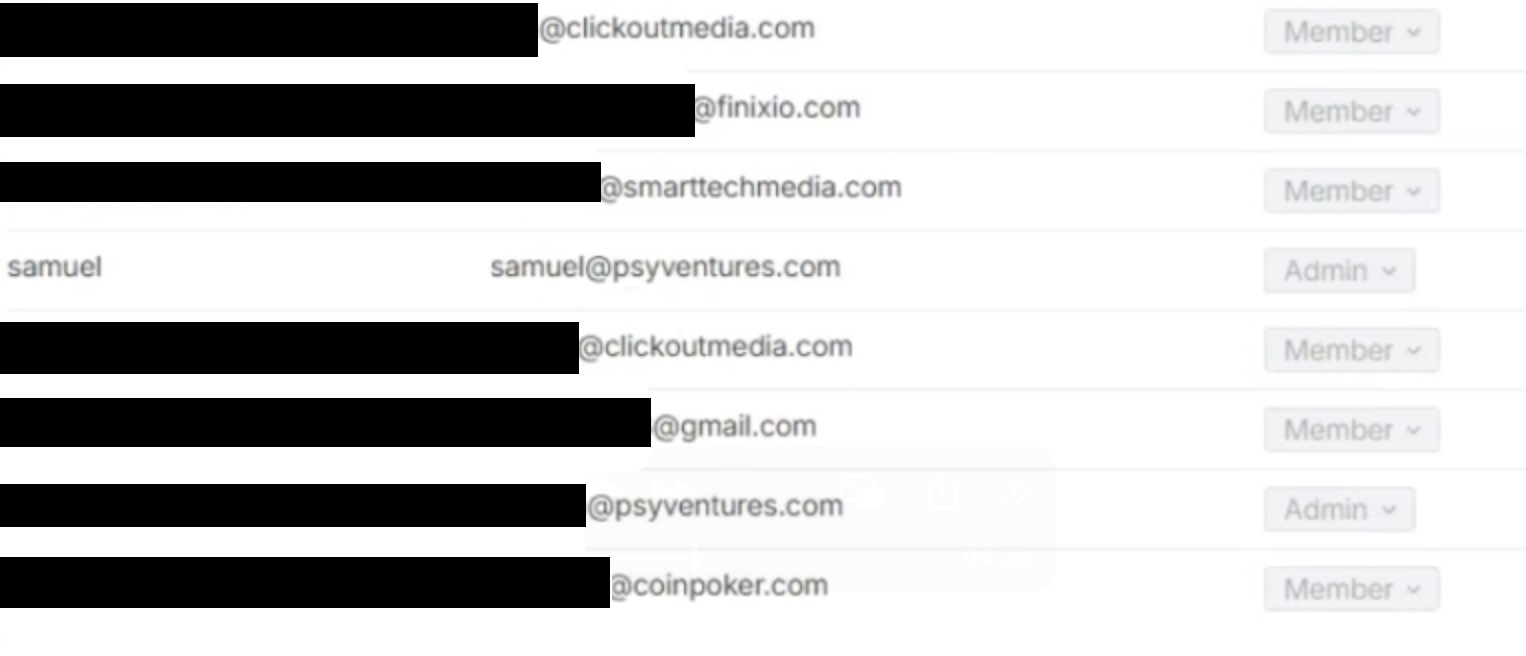

We also have Natascha:

Who is likely Natascha Jainandunsing, (who uses the business name Natascha Sing) of Brand Setter agency (see episode 1 for more detail on her).

https://www.linkedin.com/in/nataschaj/?originalSubdomain=uk

In other words, core Finixio/Clickout personnel are involved in running the SEO operation here, at least to the extent that they are listed as members, and other members have access to their contact information.

These are leaders of content, business operations, and the top guys in the whole organization, in the mix with local content heads and other rank-and-filers.

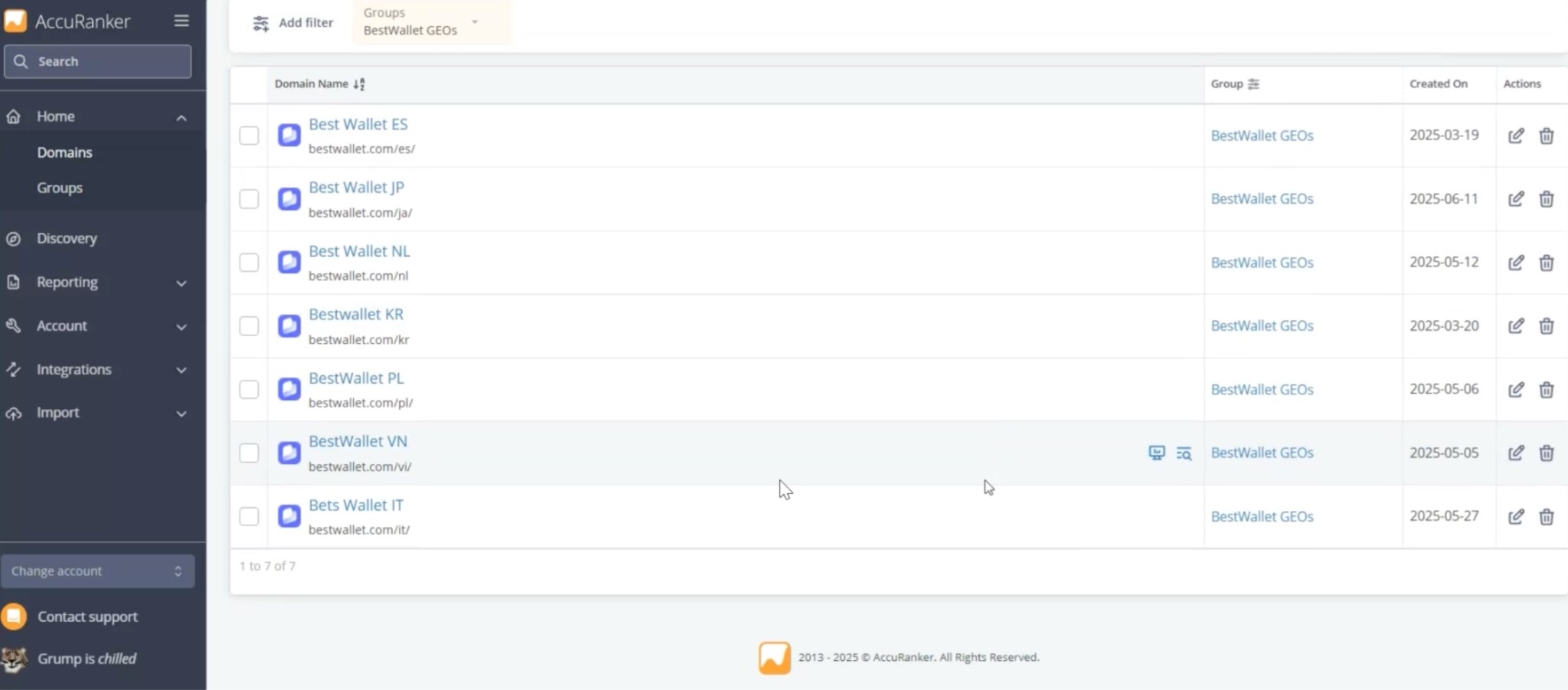

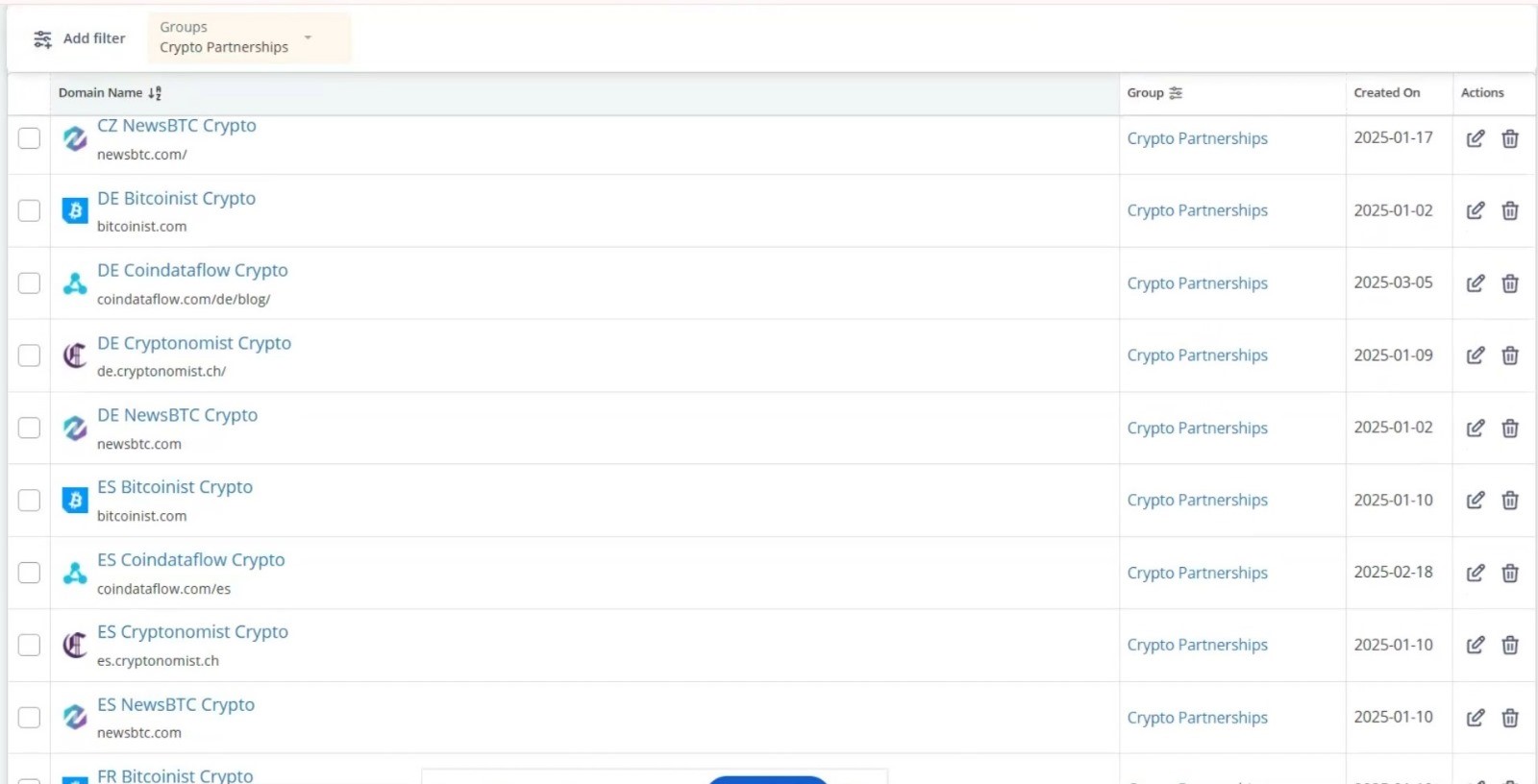

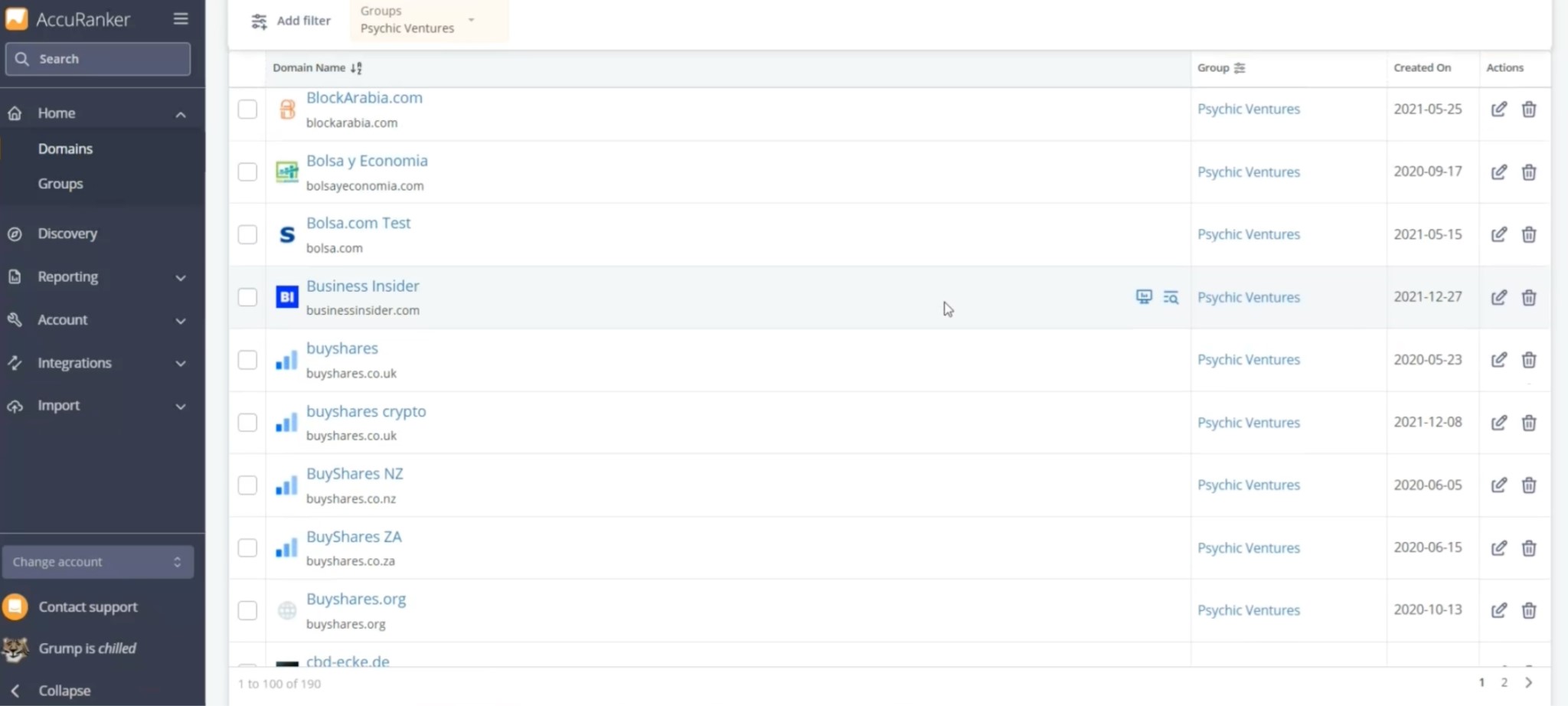

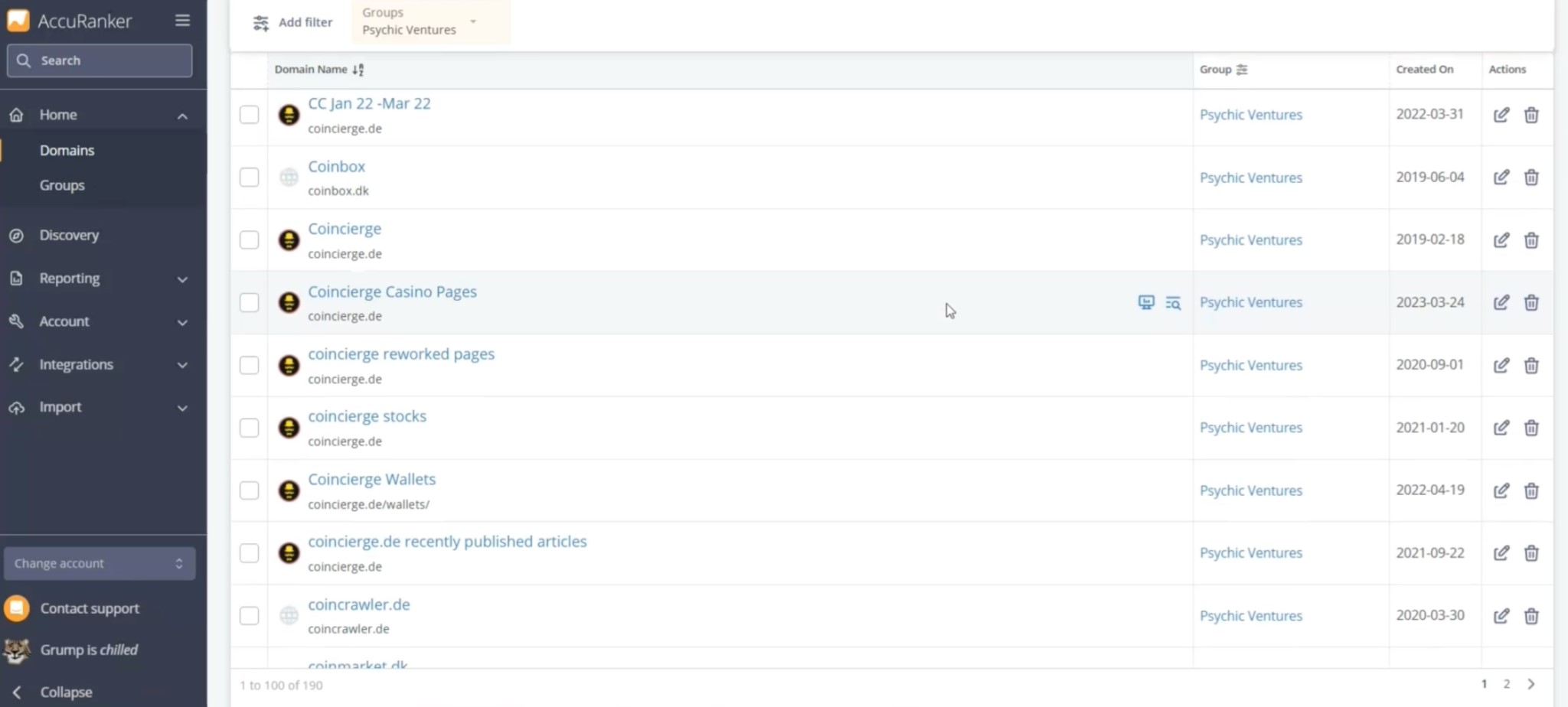

Clickout’s AccuRanker account

Meanwhile, here’s another tool, AccuRanker.

It’s a specialized tool focusing on keyword performance, and like Ahrefs, it lets you manage multiple properties.

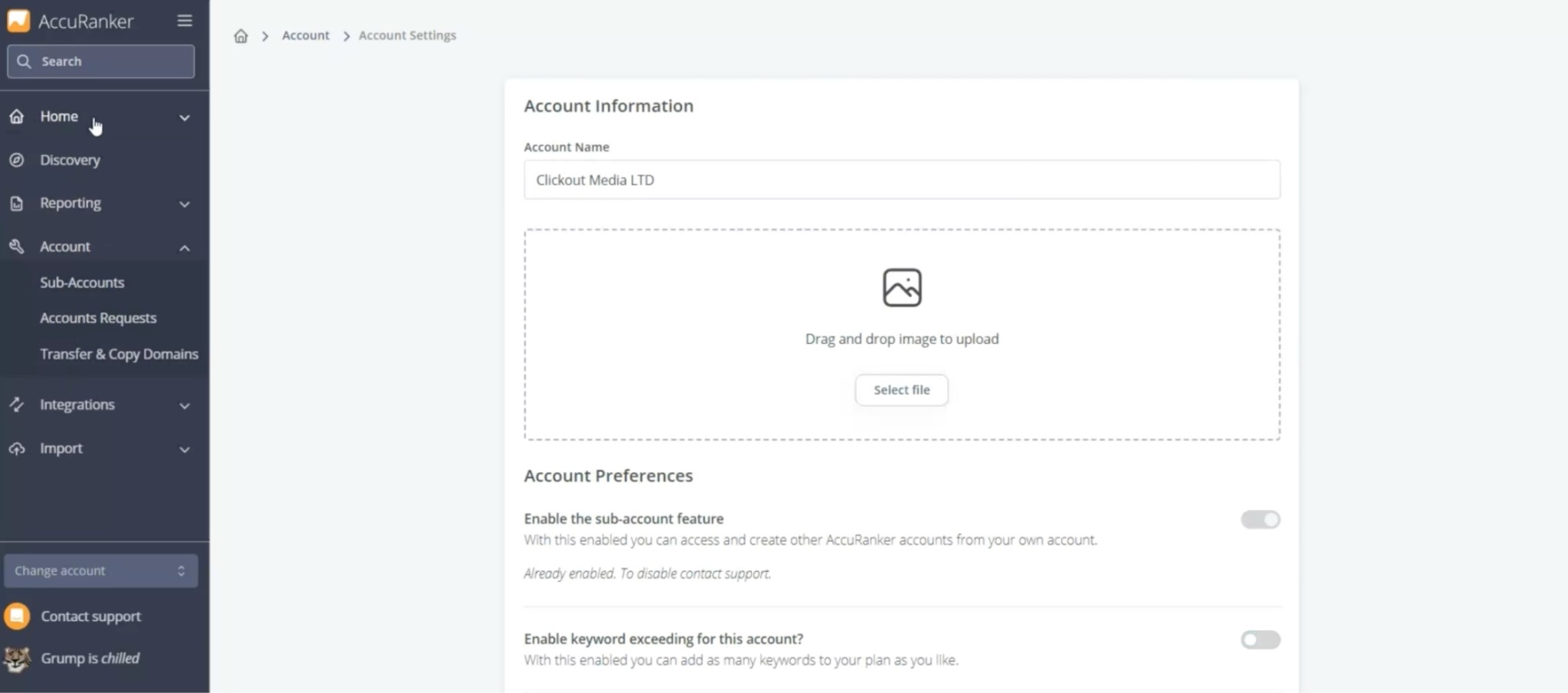

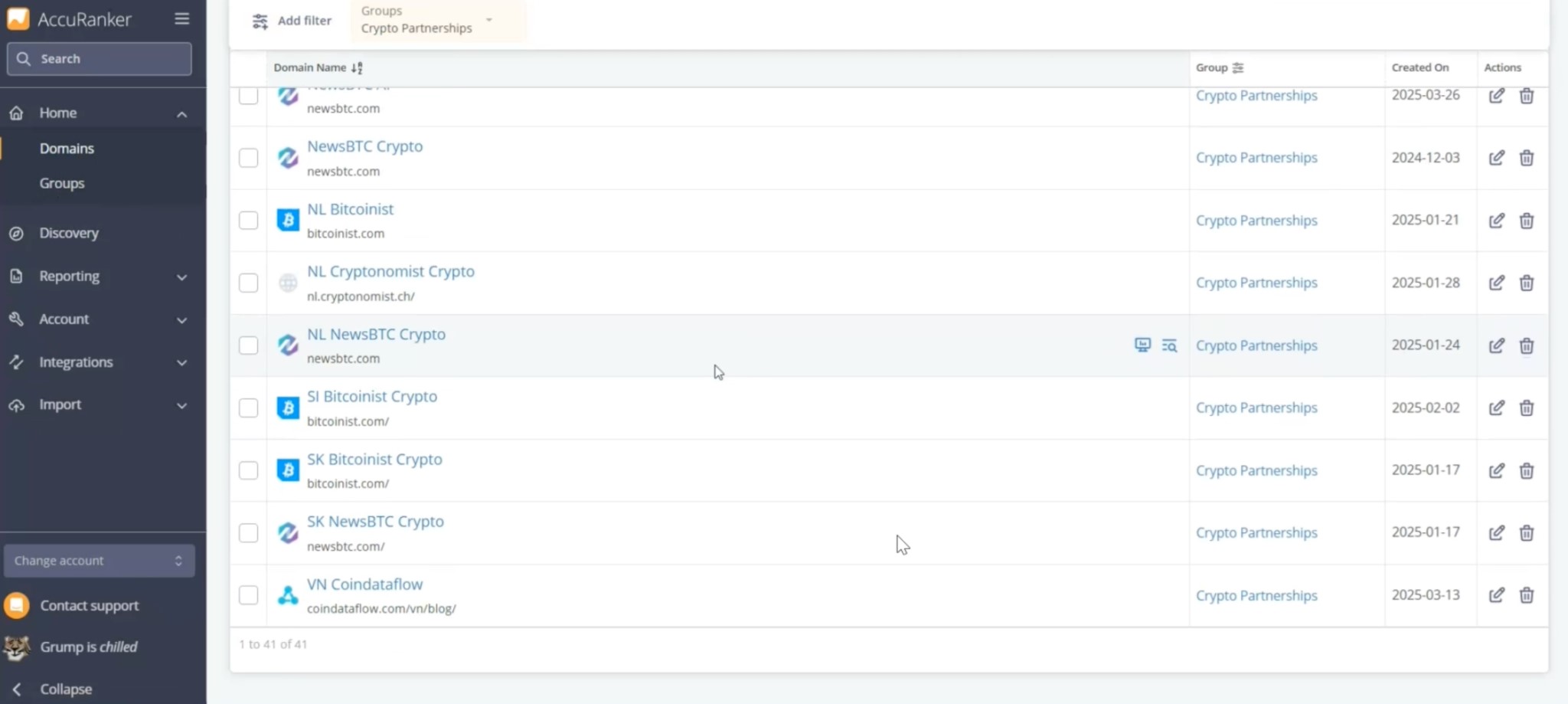

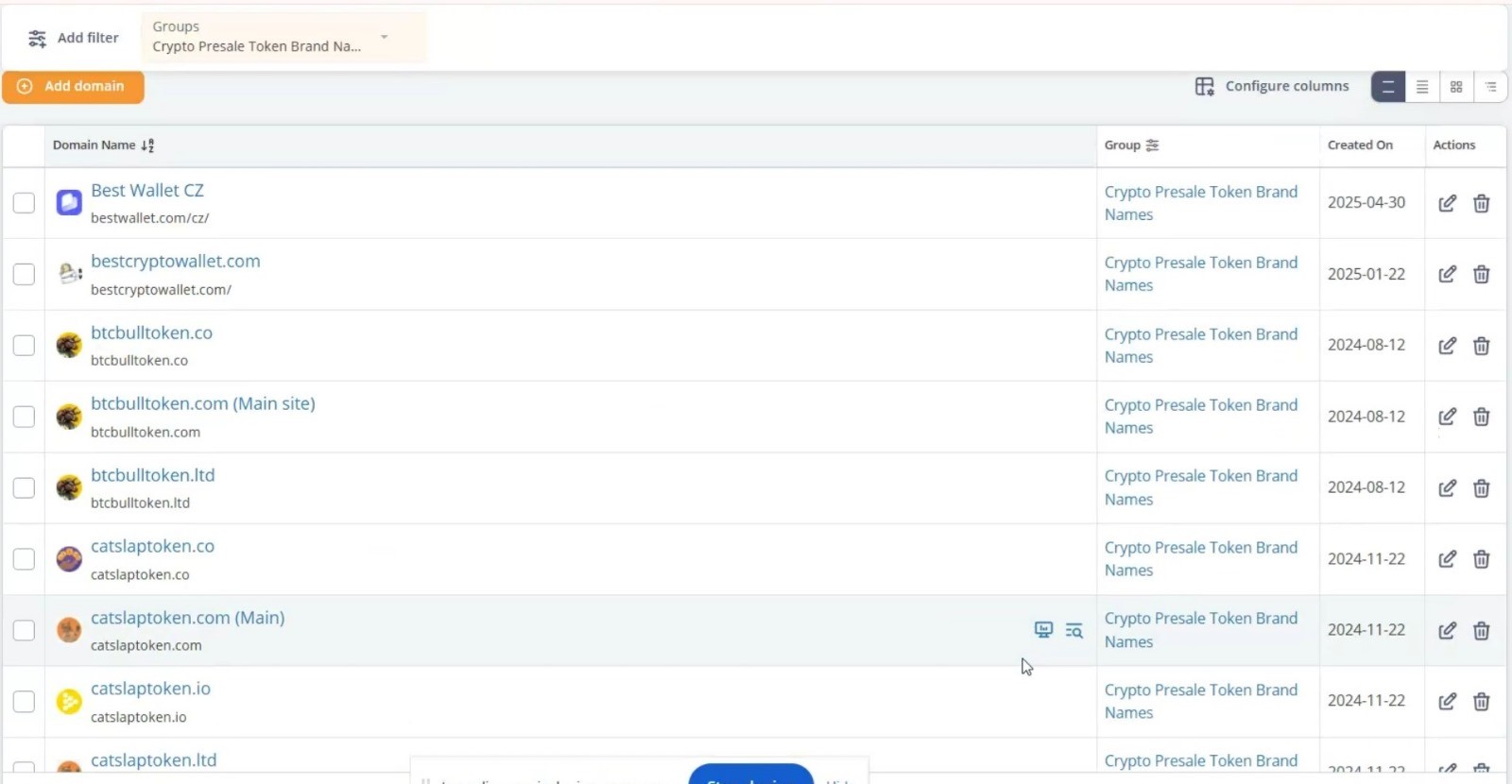

Here’s Clickout’s AccuRanker:

Above is the accounts page.

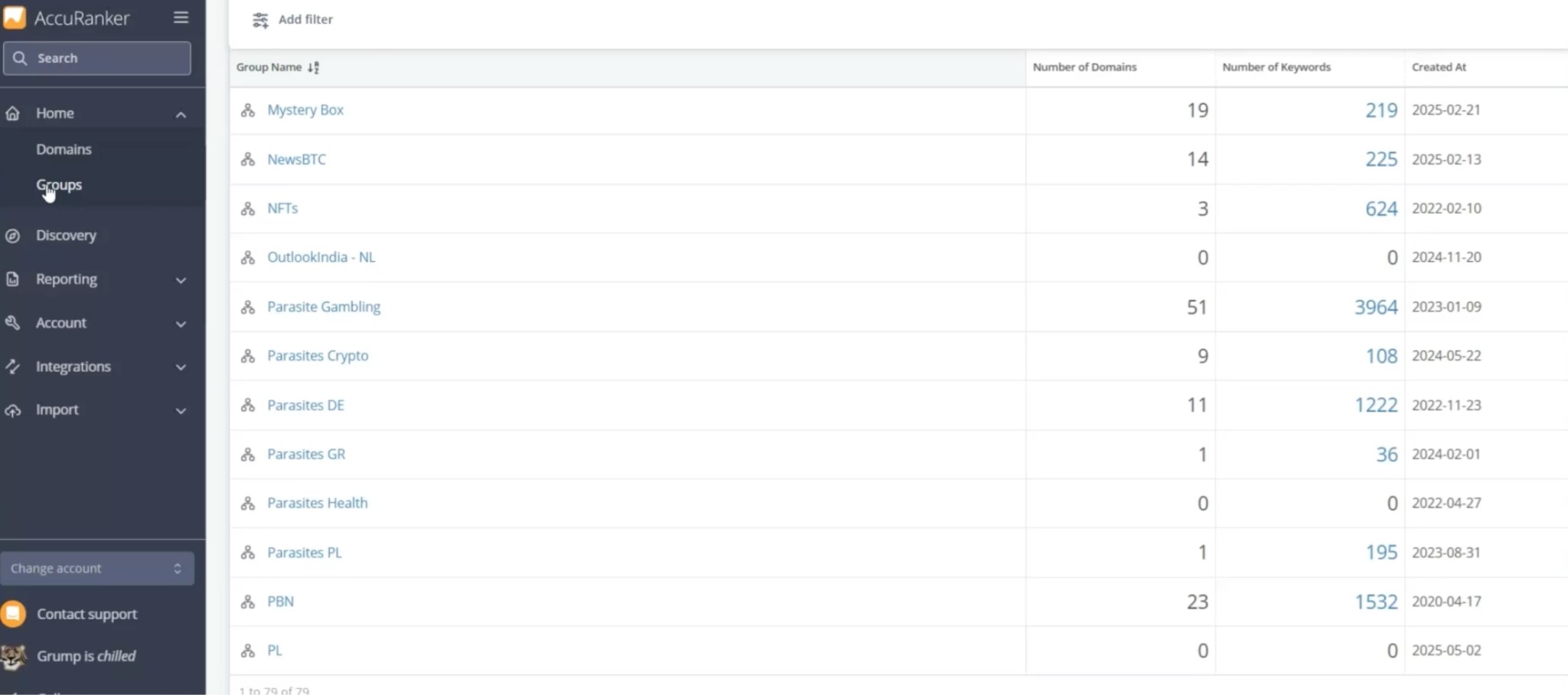

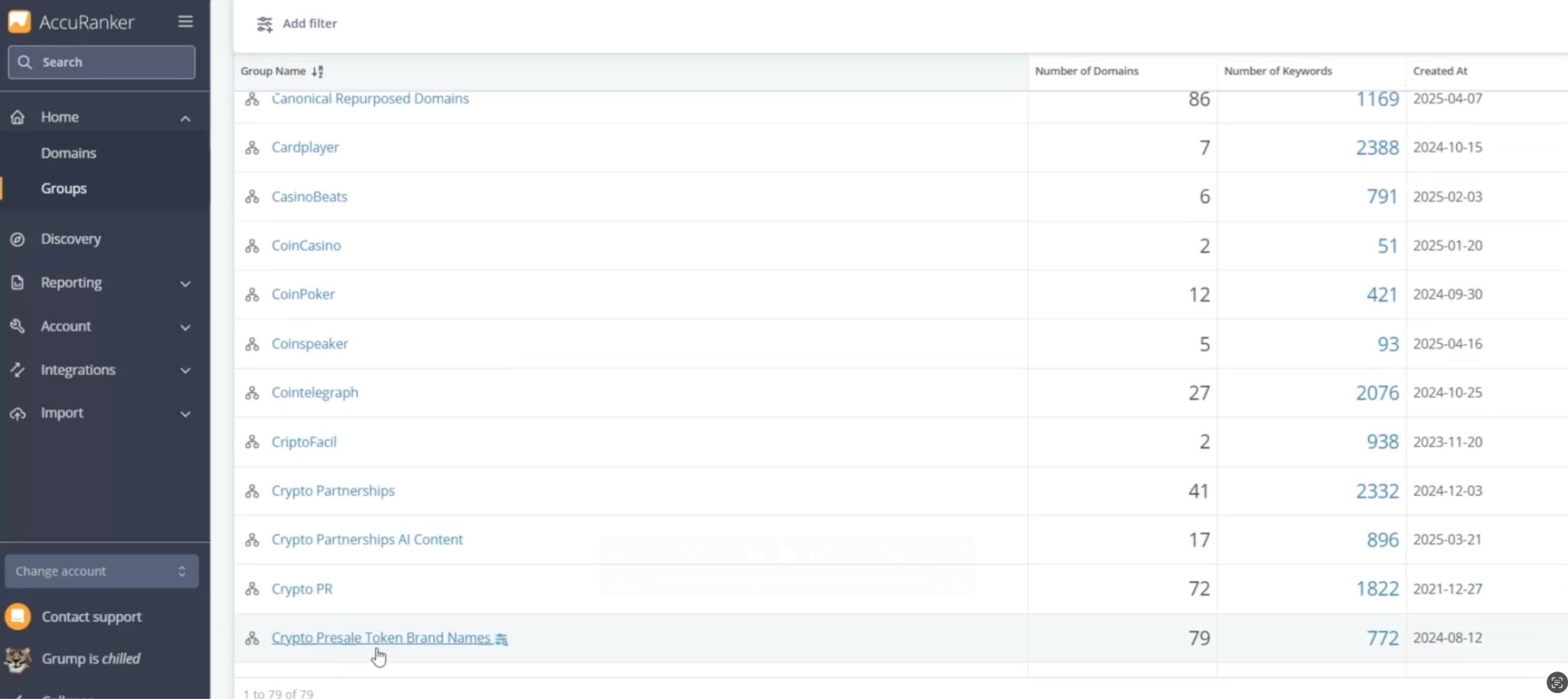

Here’s the page showing the company’s working groups — including parasite groups for crypto, gambling and health (we have no idea what’s in there, but it would be interesting to know more), and showing some location-specific groups too:

These are working groups, including names and contact details for the people involved in them.

Some of them are far more specific.

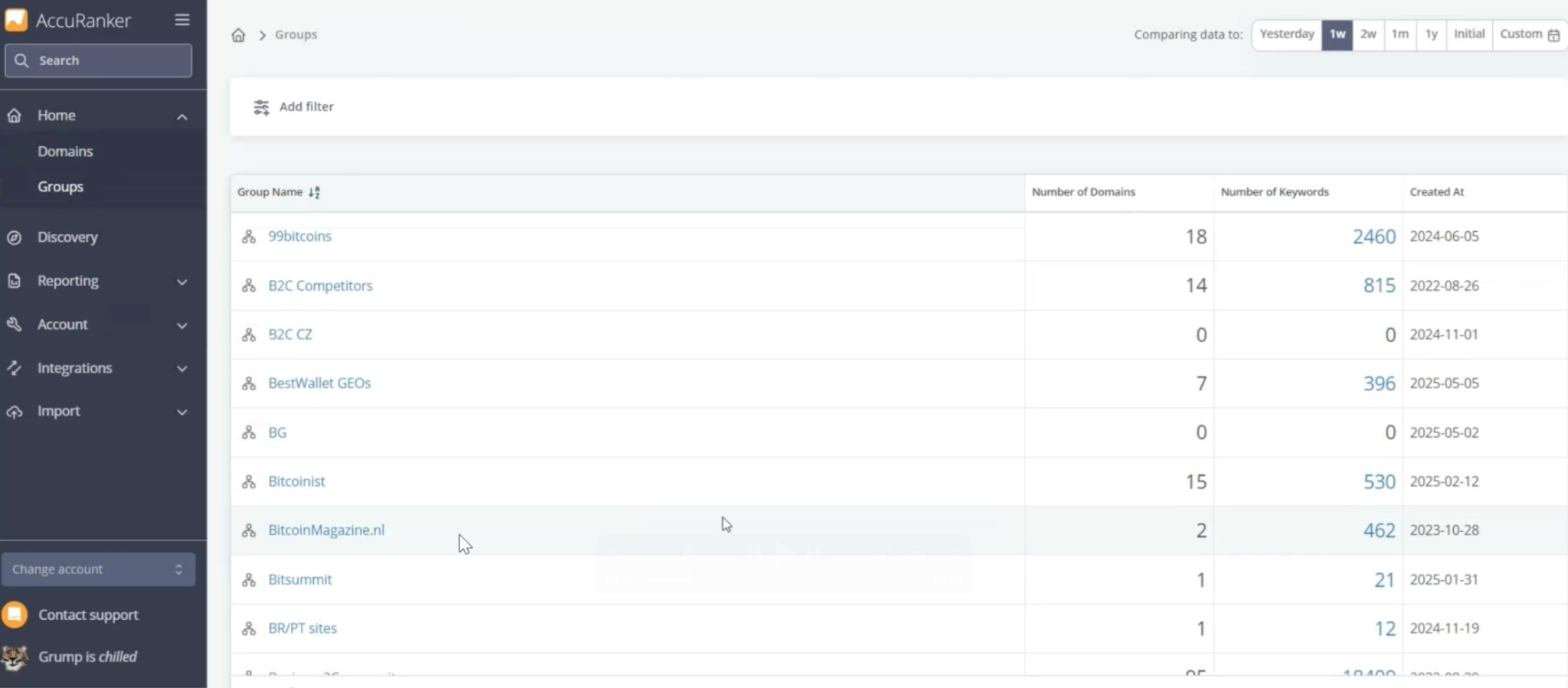

Check out 99 Bitcoins there at the top.

Note BestWallet GEOs, fourth down from the top in this list:

Here are those ‘GEOs’ (location-specific working groups) for Spain, Japan, the Netherlands, South Korea, Poland, Vietnam, and Italy:

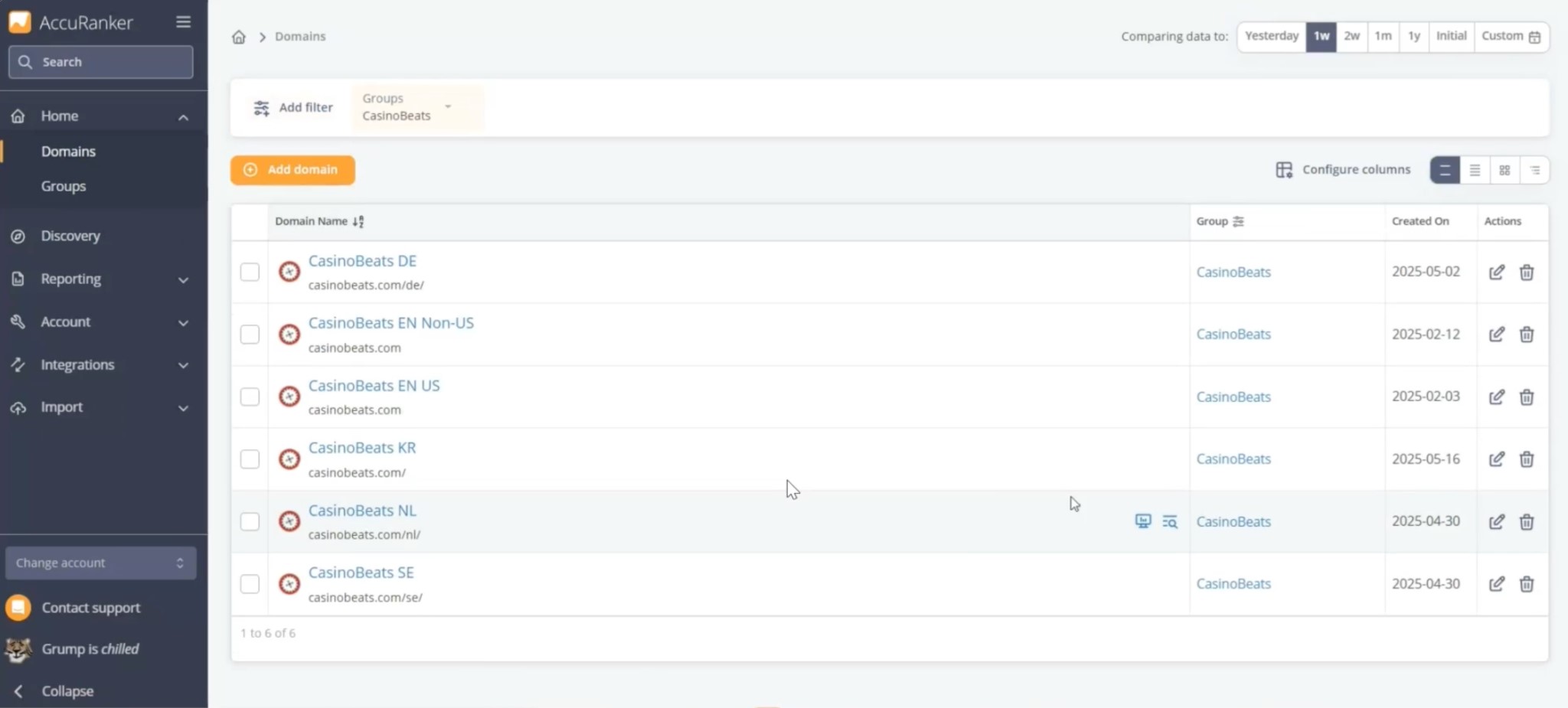

It’s the same type of picture for CasinoBeats:

There’s Germany, US and Non-US English, South Korea, the Netherlands and Sweden.

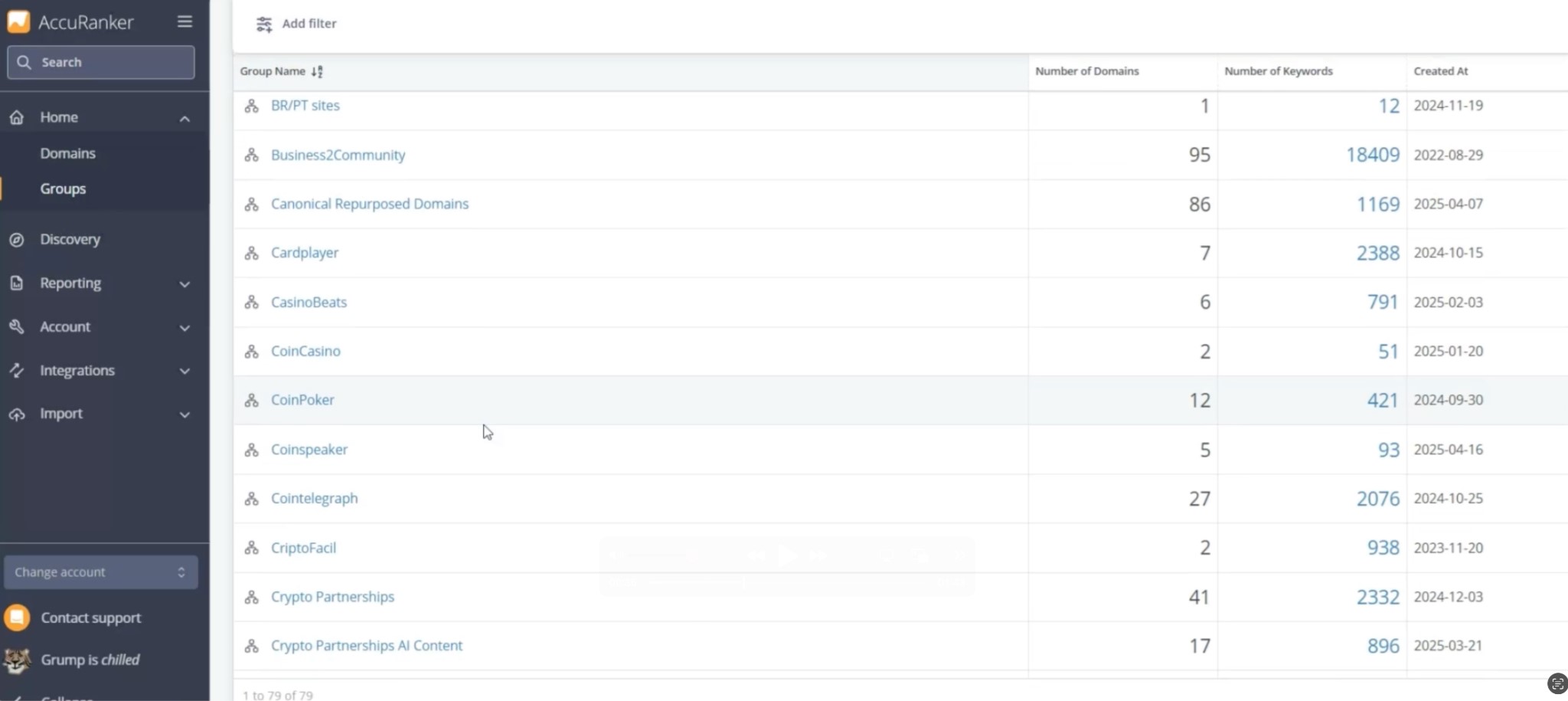

Here are some more Clickout groups, for other projects, some of which should look familiar:

Clickout likely controls a section of the CoinTelegraph site, rather than owning it outright, but they have a working group dedicated to the site. There’s also CoinPoker, CardPlayer, and CoinCasino, among other familiar names.

The drop domains

Note also ‘Canonical Repurposed Domains’ (drop domains).

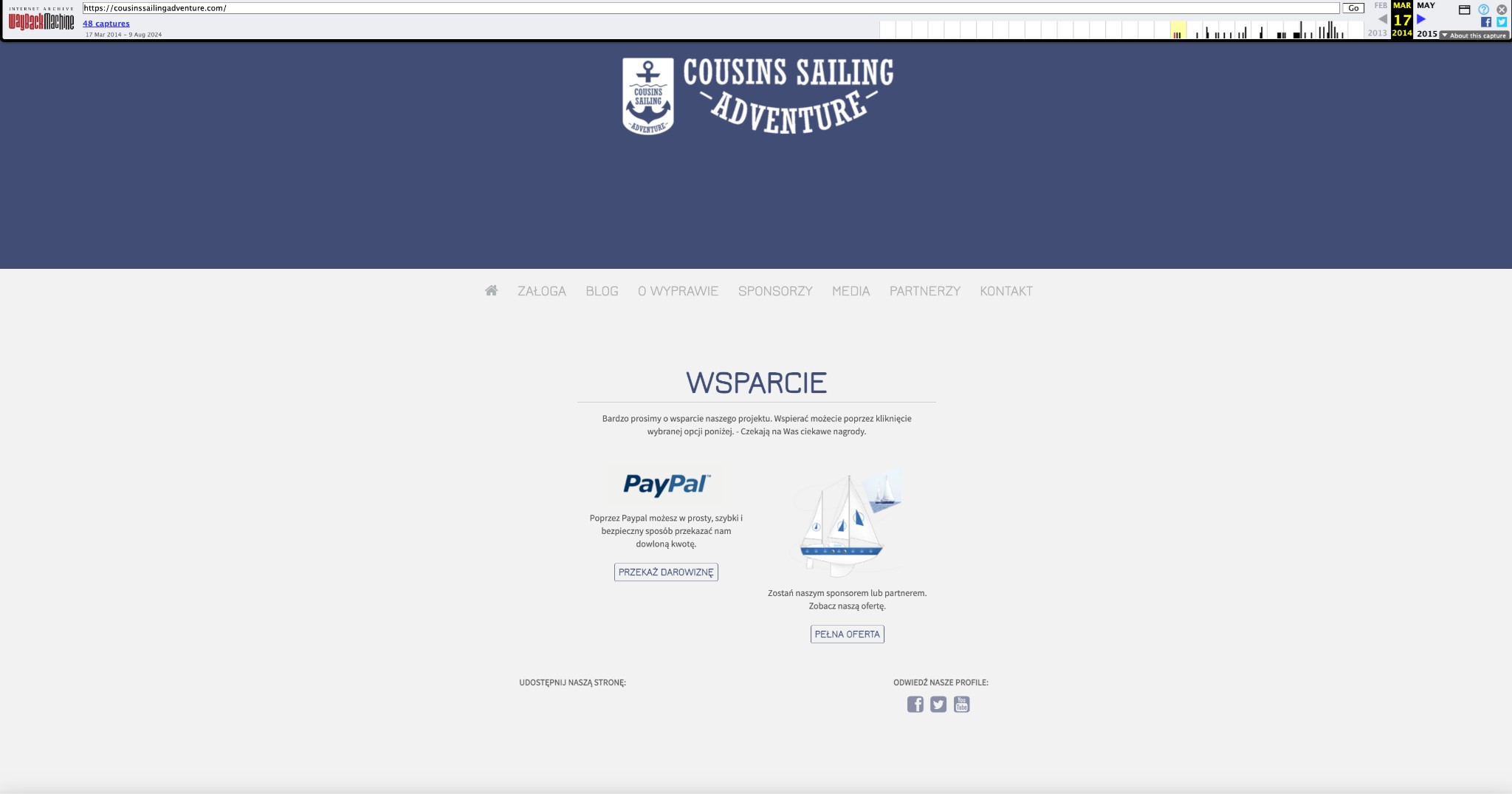

Some of these look wildly unrelated to what Clickout does — or to anything else cohesive. For example, cousinssailingadventure.com, once a Polish-language website:

https://web.archive.org/web/20140317101050/https://cousinssailingadventure.com/

Apparently devoted to exactly what it says on the tin.

Now it looks like this:

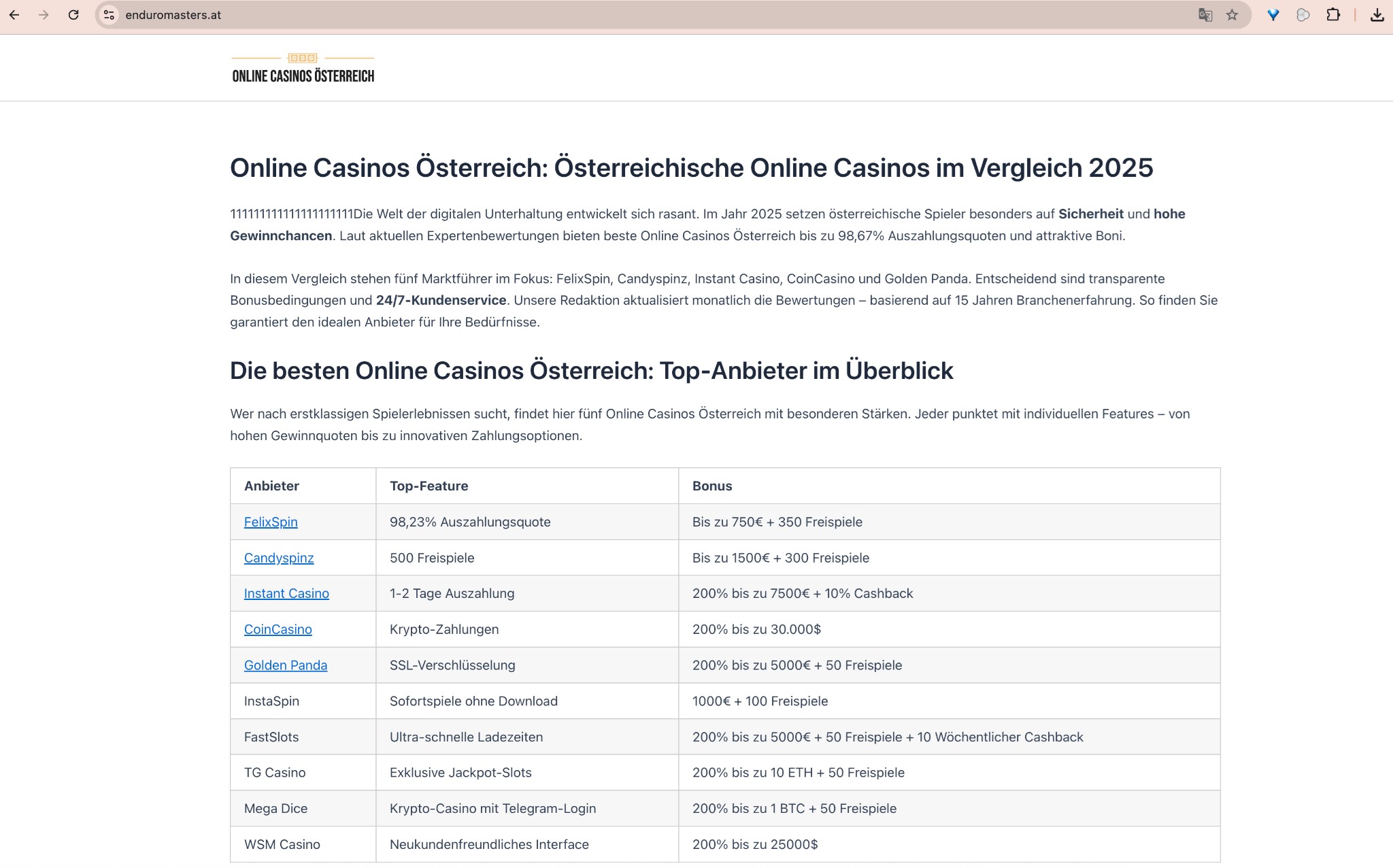

Or EnduroMasters.at, dedicated to dirt biking:

https://web.archive.org/web/20130602042144/http://www.enduromasters.at/em/

Which now looks like this:

http://www.enduromasters.at/em/

What do dirt biking, sailing, and all these other drop domains have in common? It’s not their subject matter. And while these are venerable, decade-old domains, they’re also clunkers with tiny Domain Ranking (26 and 18, for the ones above; DR isn’t the whole story, but these sites don’t look like obvious winners).

What they likely do have is valuable inbound links, based on the site’s previous subject matter. For example, enduromasters.com has backlinks from 1000ps.de, a major German motorcycle site:

Links of this quality, localized to Germany and thus likely to improve a site’s performance in a specific country, don’t always guarantee traffic to a drop domain. In fact I’d say 90% of the time a drop domain is just a waste of money. But when they do work they can be spectacularly successful.

Spaceport Sweden, which I’ve talked about before, is a good example of a massively successful drop domain.

These are the drop domains Clickout Media uses for the authority they’ve accumulated since they’ve been up.

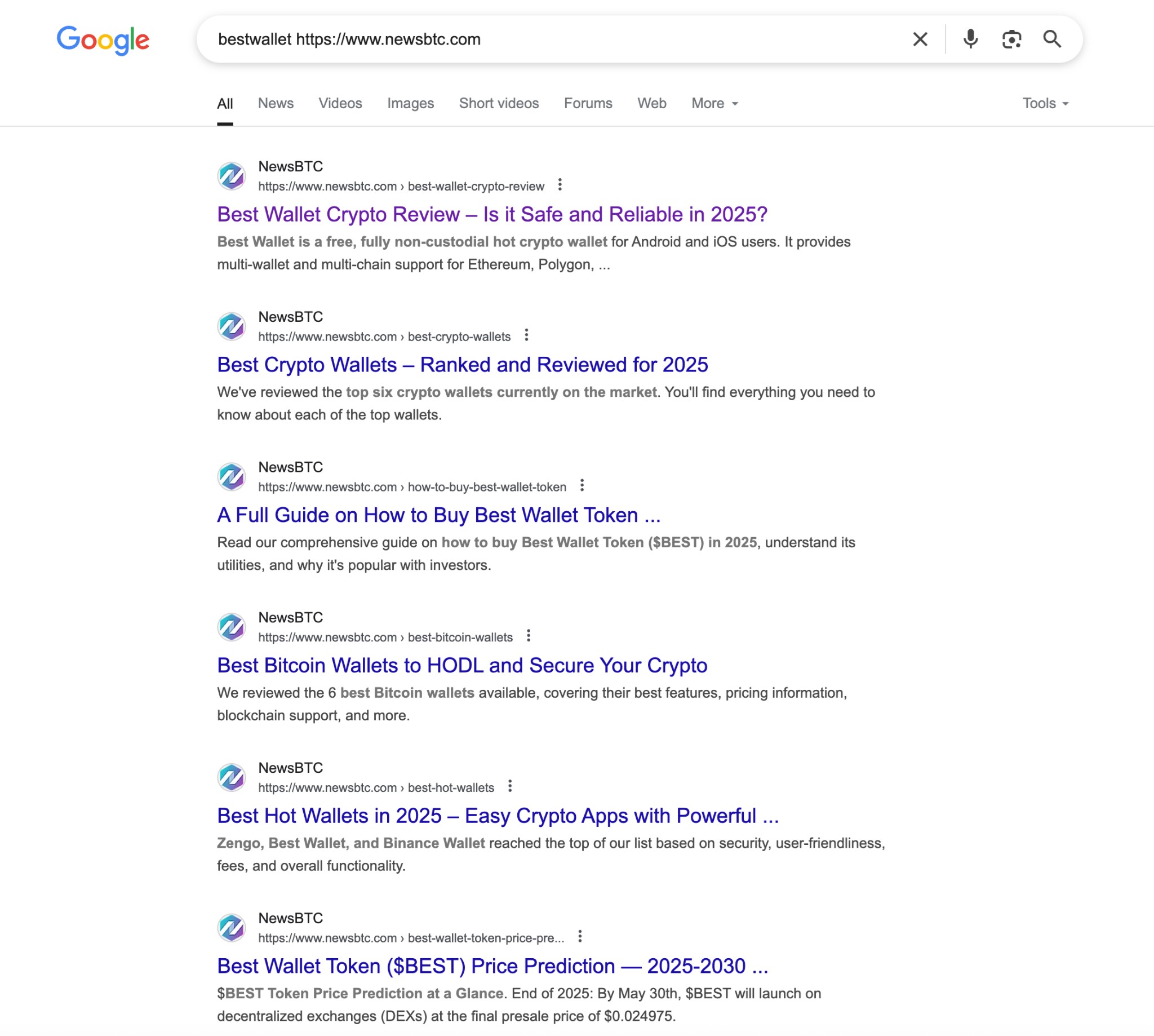

Then there’s crypto partnerships.

Presumably, it’s such partnerships that make search results pages like these possible:

There’s Bitcoinist:

We suspected Finixio/Clickout were involved in this site, but until now there was no evidence. Now it looks pretty conclusive, and it makes perfect sense why Dogeverse boasts of Bitcoinist’s coverage of the project: while they don’t own it, they’re working together.

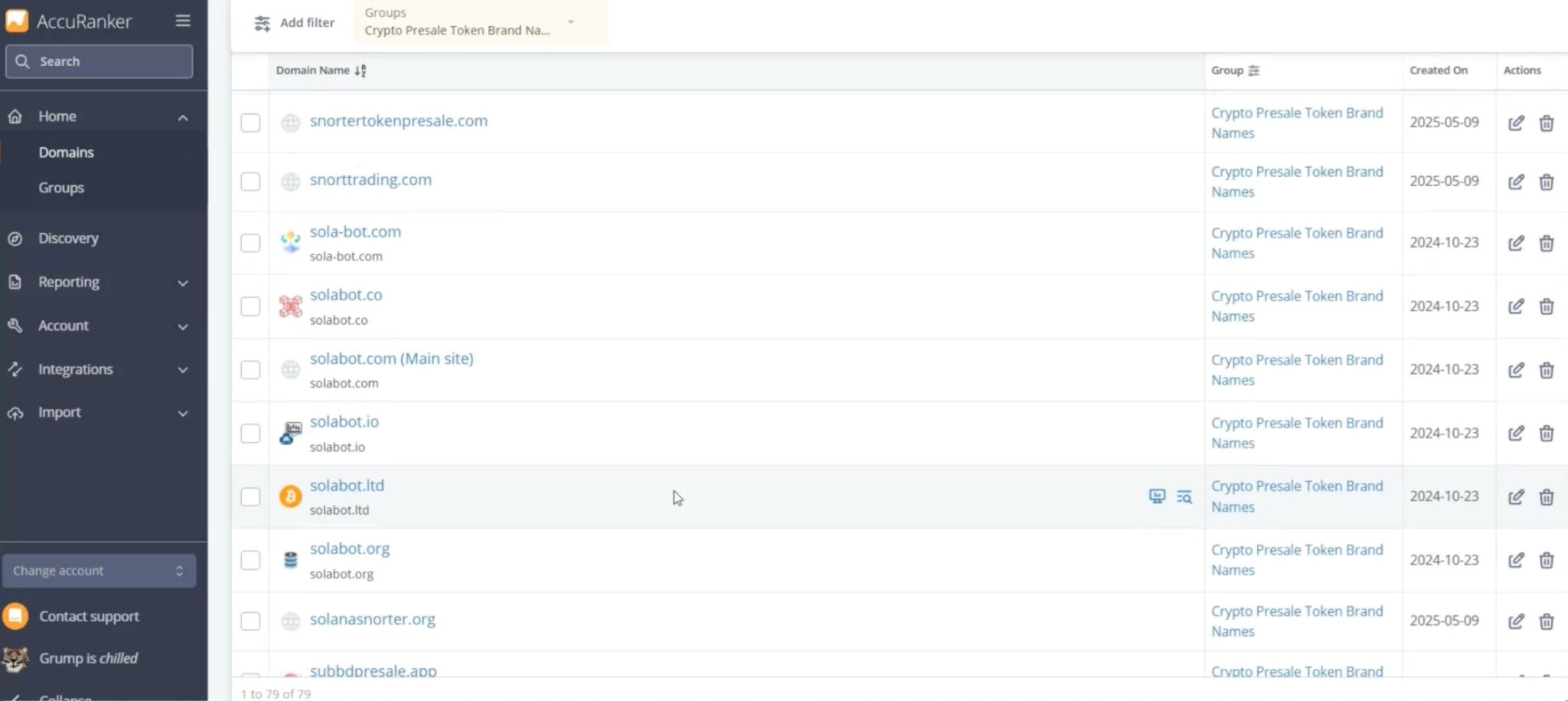

Here, at the bottom of the AccuRanker page, is ‘Crypto Presale Token Brand Names.’

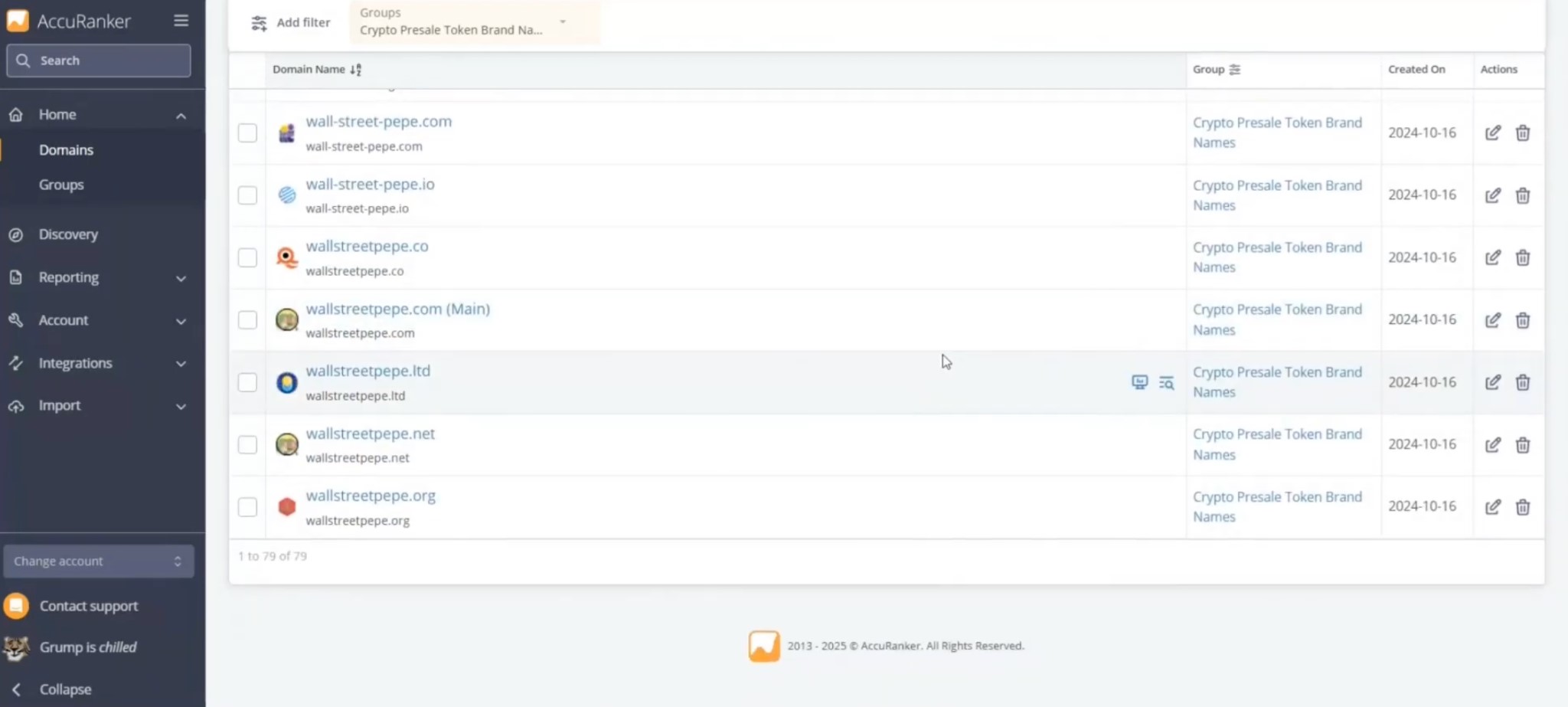

Let’s take a look at some of the crypto presales in the group. Like Wall Street Pepe:

Check it out: there’s a list of alternate domains including:

- wall-street-pepe.com

- wall-street-pepe.io

- wallstreetpepe.co

- wallstreetpepe.com

- wallstreetpepe.ltd

- wallstreetpepe.net

- wallstreetpepe.org

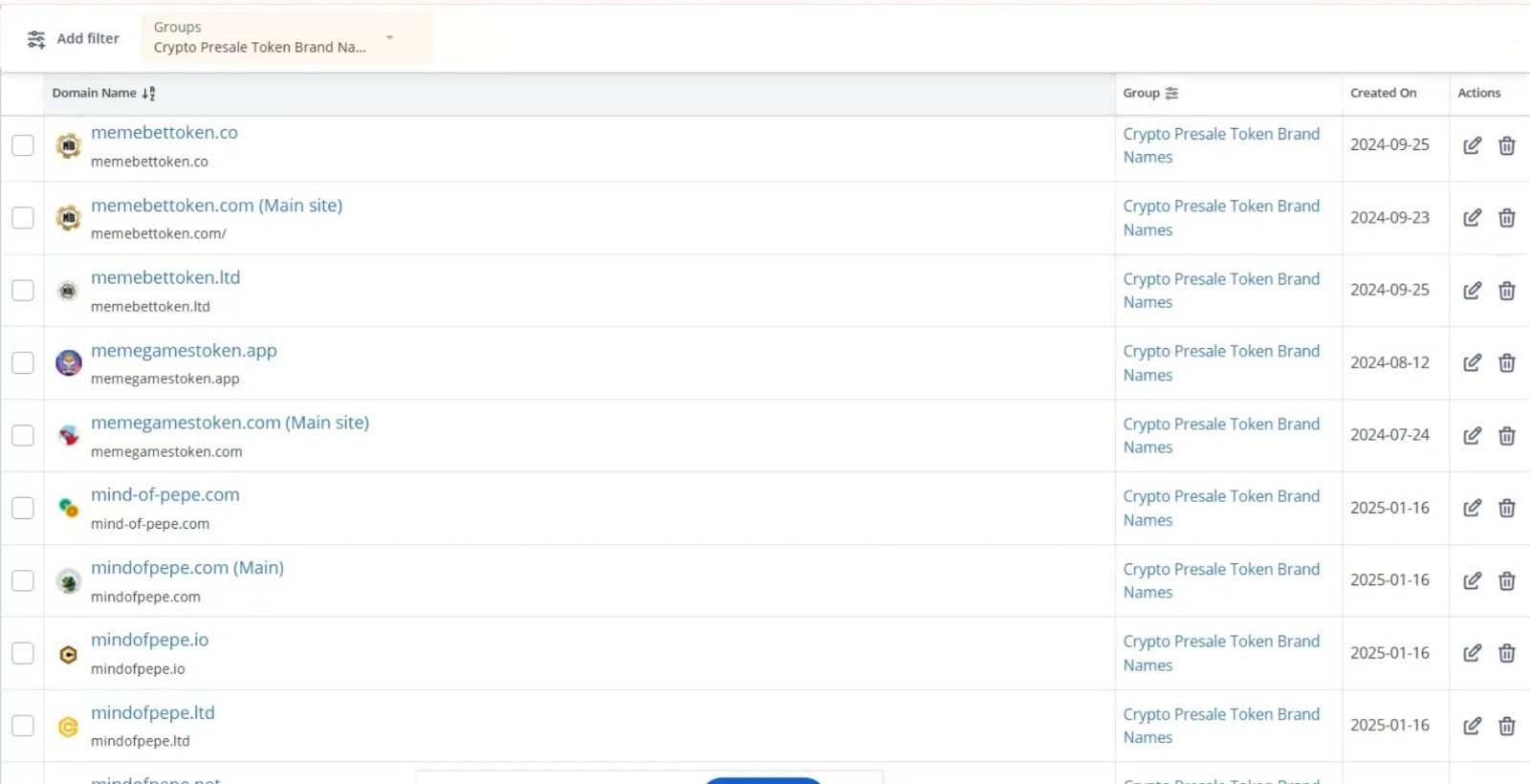

Or Mind of Pepe:

Notice that there are several Mind of Pepe domains:

- mind-of-pepe.com

- mindofpepe.com

- mindofpepe.io

- mindofpepe.ltd

- mindofpepe.net

- mindofpepe.org

These all offer slightly different versions of the pitch.

Or how about Best Wallet?

Note that this is the Best Wallet token, not the wallet itself.

These are presumably only active projects, so other projects we know are Finixio/Clickout team assets aren’t listed. But the picture matches both what we’ve uncovered from research and what we’ve heard from sources: there are 79 active projects in total, at the time of writing.

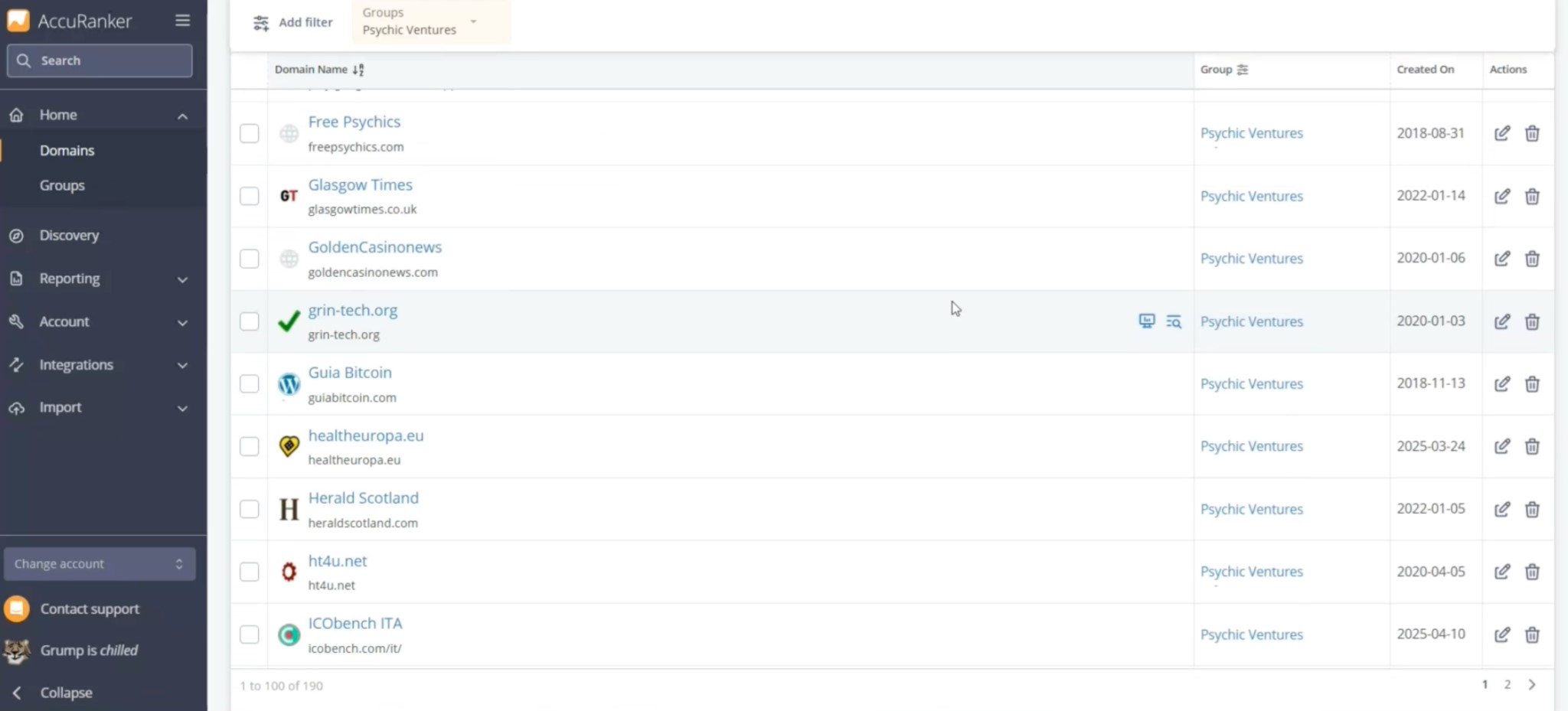

One of the major groups in Clickout’s AccuRanker is Psychic Ventures, which manages 190 domains, including…

…Business Insider…

…CoinCierge (and check out how granular these pages are — these are different sub-pages for casino, reworked pages, wallets, stocks…

Then there’s GoldenCasinonews, ICOBench — a venerable crypto site long suspected to be a Finixio asset — and Herald Scotland, which it seems unlikely that Clickout owns. It’s much more likely that either that site has a crypto or gambling portal built into it, and Clickout manages that, or…

https://www.heraldscotland.com/news/23206539.11-cryptocurrencies-look-2023/

…’sponsored content.’ Found it — courtesy of Crypto PR, founded by Adam Grunwerg.

There’s some health stuff mixed in and a bunch of online psychics on the second page too.

Solaxy: Finixio’s business as usual

There’s also the most recent Finixio team launch: Solaxy.io.

https://solaxy.io/

Solaxy is allegedly a layer 2 for the Solana blockchain. Layer 2 solutions operate as blockchains on top of another blockchain, providing greater transaction speeds at lower costs.

It’s registered in the British Virgin Islands, you’ll be shocked to learn:

https://solaxy.io/assets/document/whitepaper.pdf

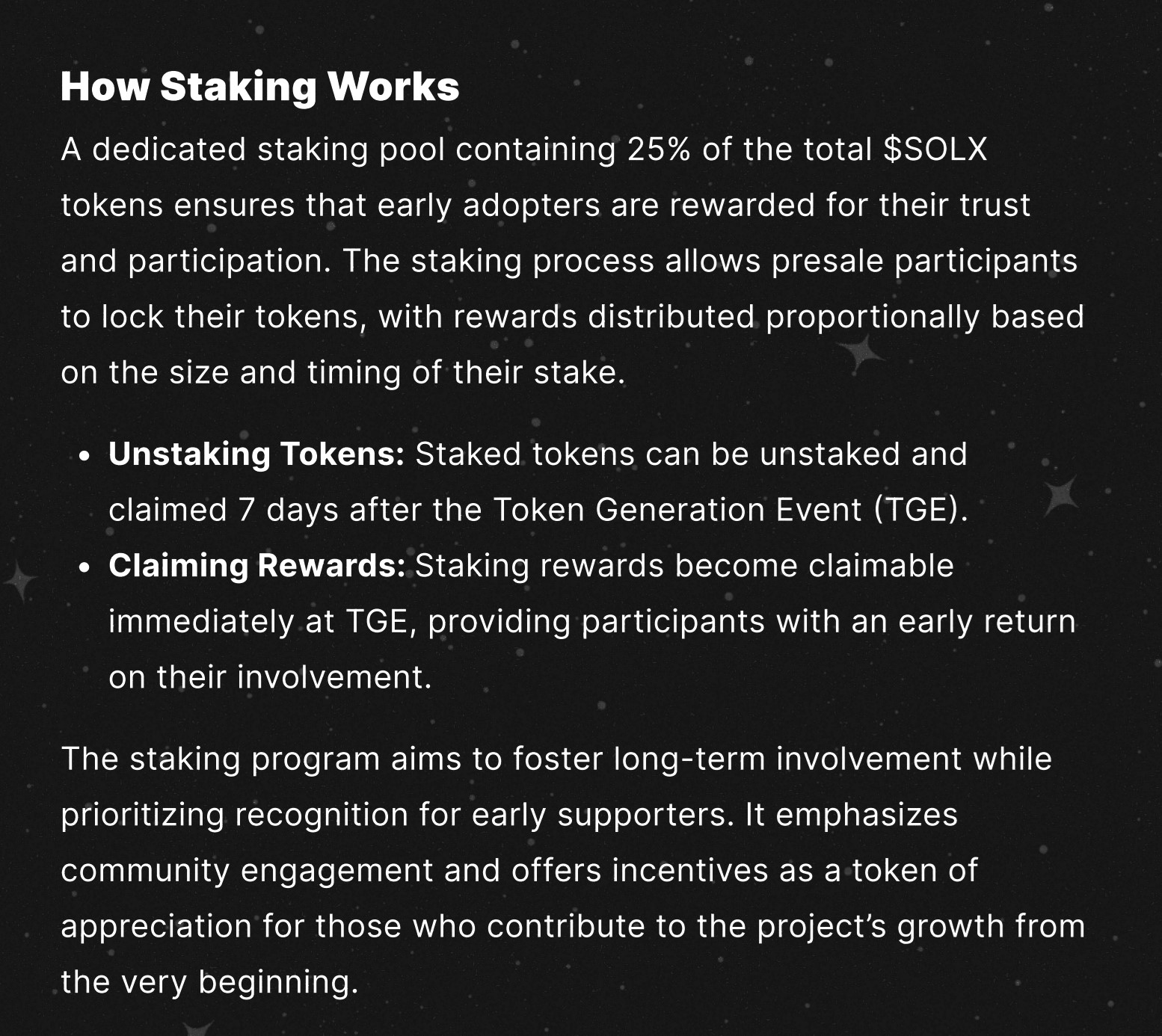

The white paper doesn’t name a single member of the team. What it does do is warn purchasers that their staked tokens won’t be available until seven days after the token launches:

It’s tempting to say this is buried in the small print, but that seems a little unfair to a 16-page white paper that’s all in 18-point type. It is an unusual stipulation, one that leaves some token purchasers at the mercy of any changes in token price that might happen between launch and the end of the seven-day window. And for Finixio/Clickout team-controlled crypto projects, that seven-day window usually involves a precipitous collapse in price.

When Solaxy had just launched, price looked unusually promising. Here’s the first three days:

But then again, here’s the first five weeks, to August 6:

https://www.coingecko.com/en/coins/solaxy

We haven’t been able to tie any of the Finixio team directly to Solaxy itself. While it appears in Crypto Rug Muncher’s list of Finixio/Clickout projects:

https://x.com/CryptoRugMunch/status/1886805232878858528

We haven’t investigated every project on this list. (We have dug deep enough into Wall Street Pepe, in particular, to know that it’s a Finixio operation.)

Anyway, watch the entire accuranker video here:

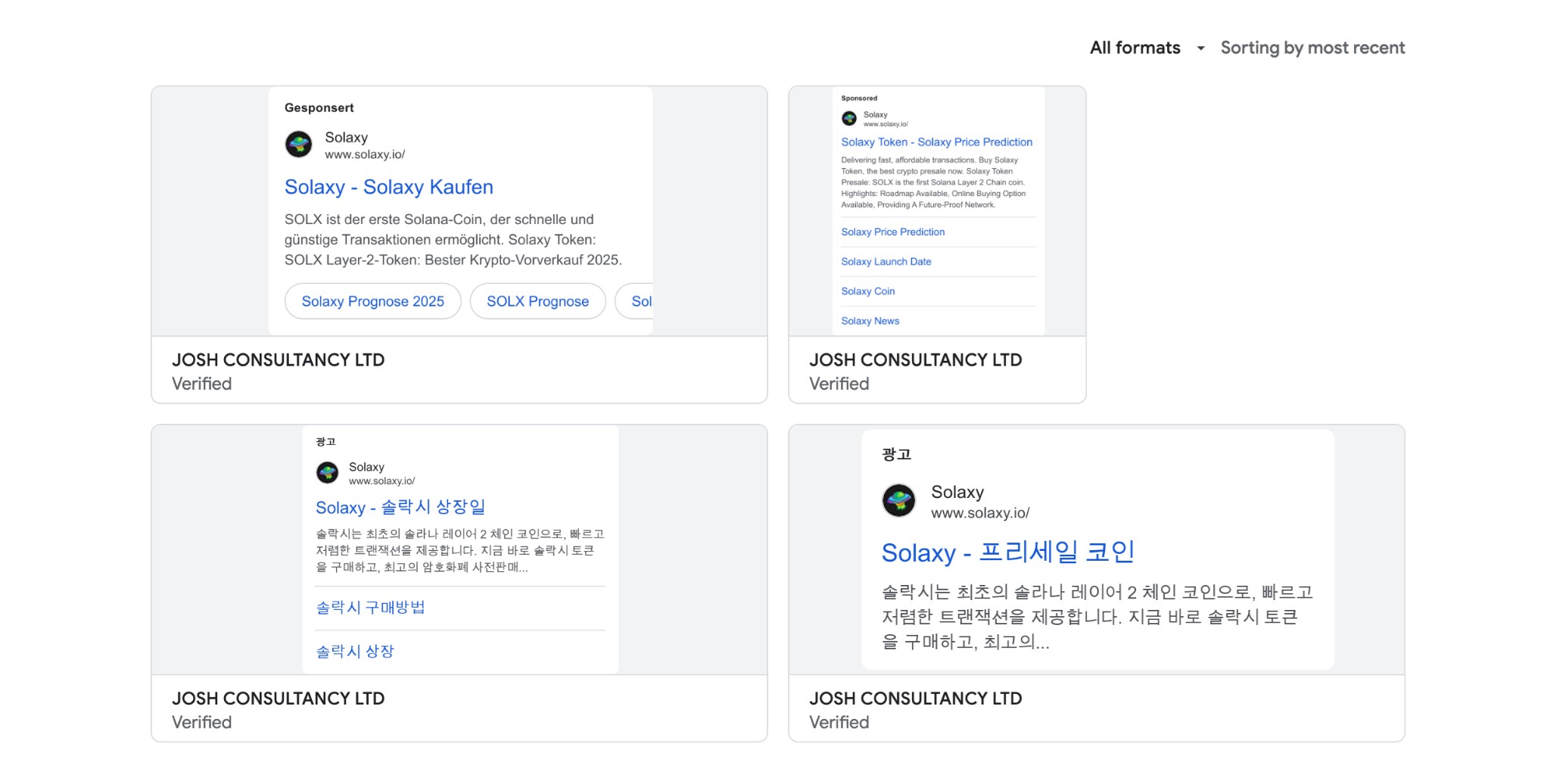

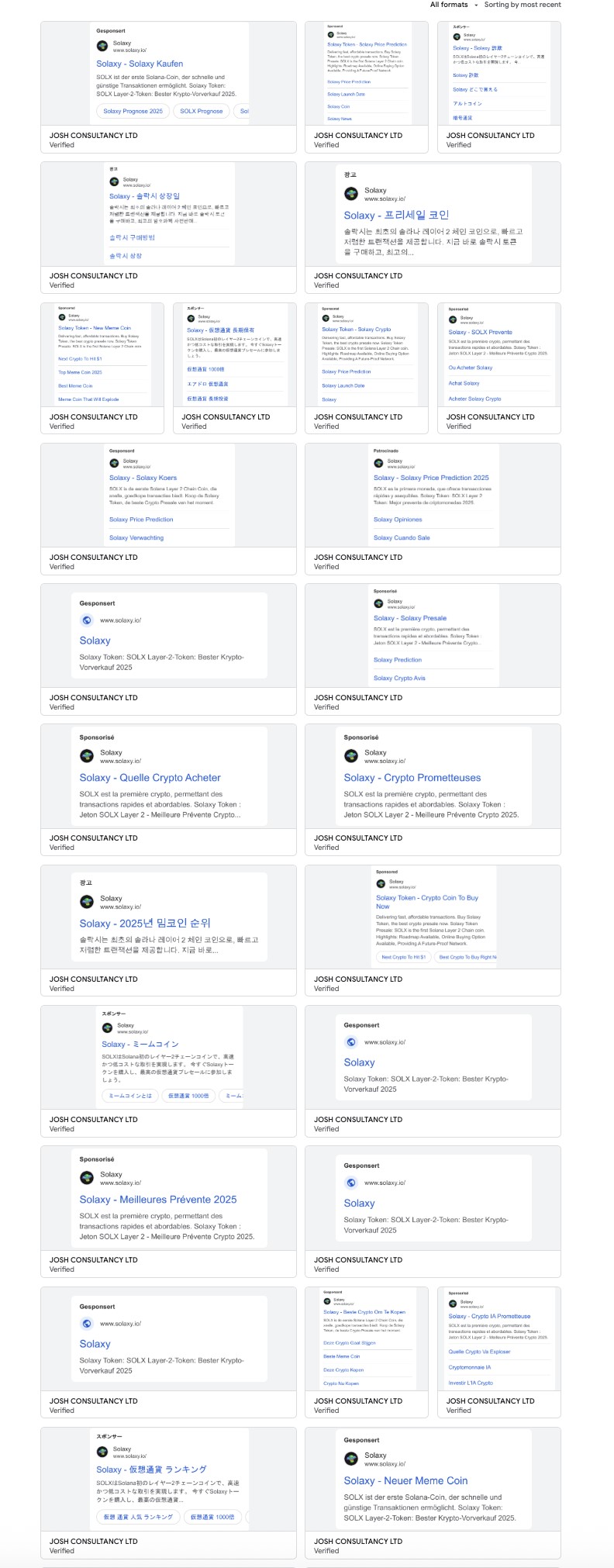

However, we do know who’s handling advertising for the project.

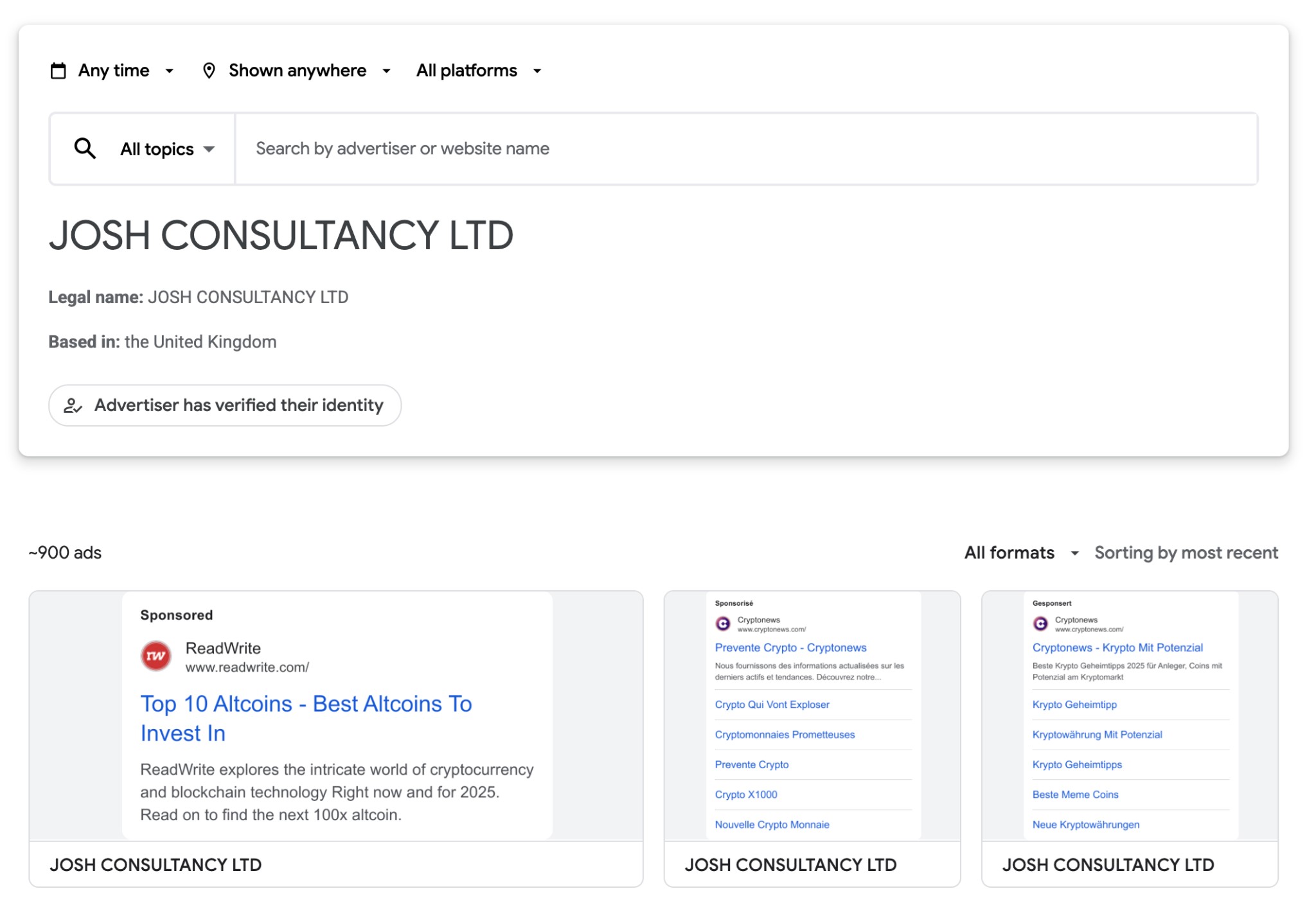

https://adstransparency.google.com/?origin=ata®ion=anywhere&domain=solaxy.io

This is the Google Ads Transparency Center page for a company called Josh Consultancy Ltd, which is handling paid ads for Solaxy.

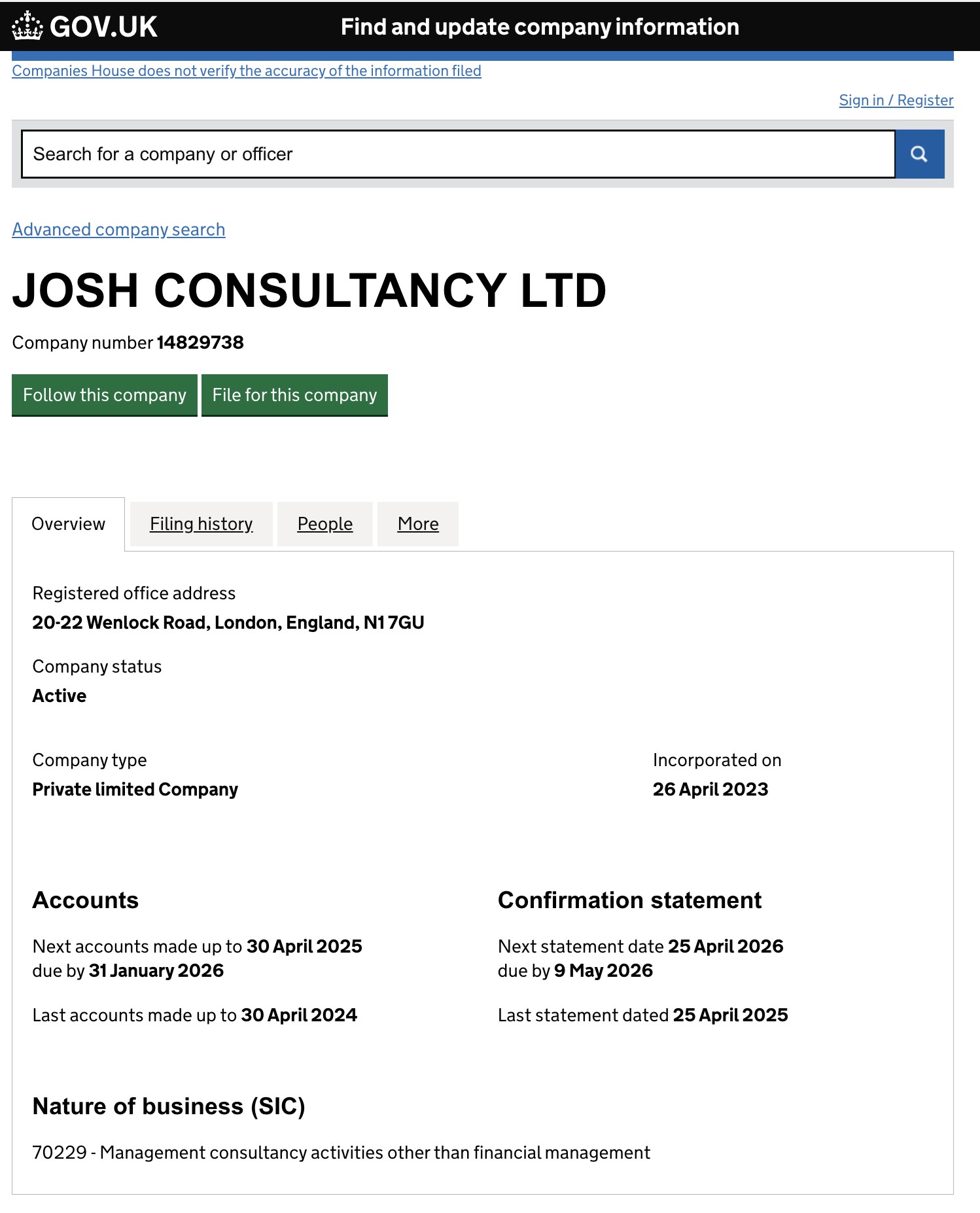

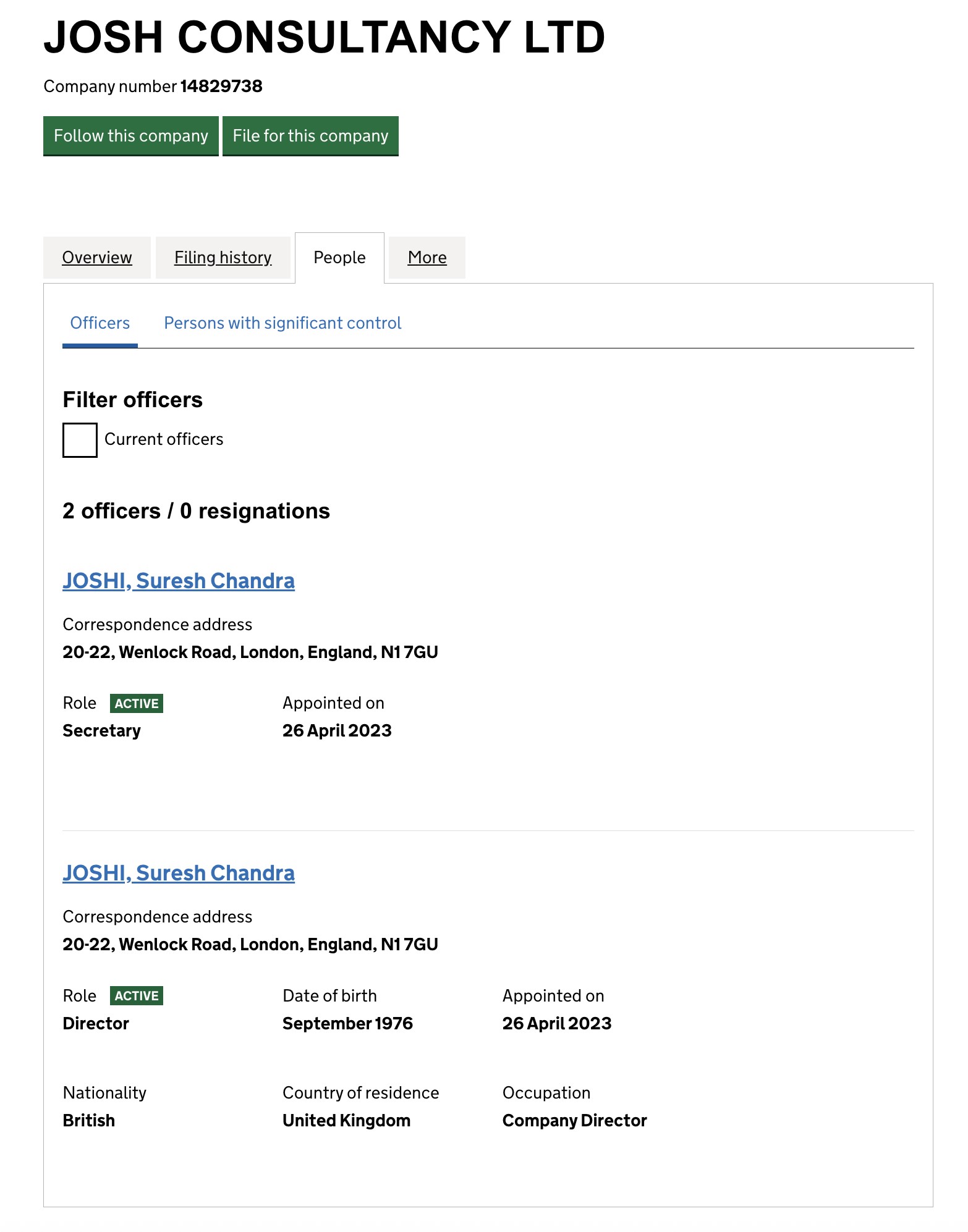

Josh Consultancy Ltd is registered in the UK:

https://find-and-update.company-information.service.gov.uk/company/14829738

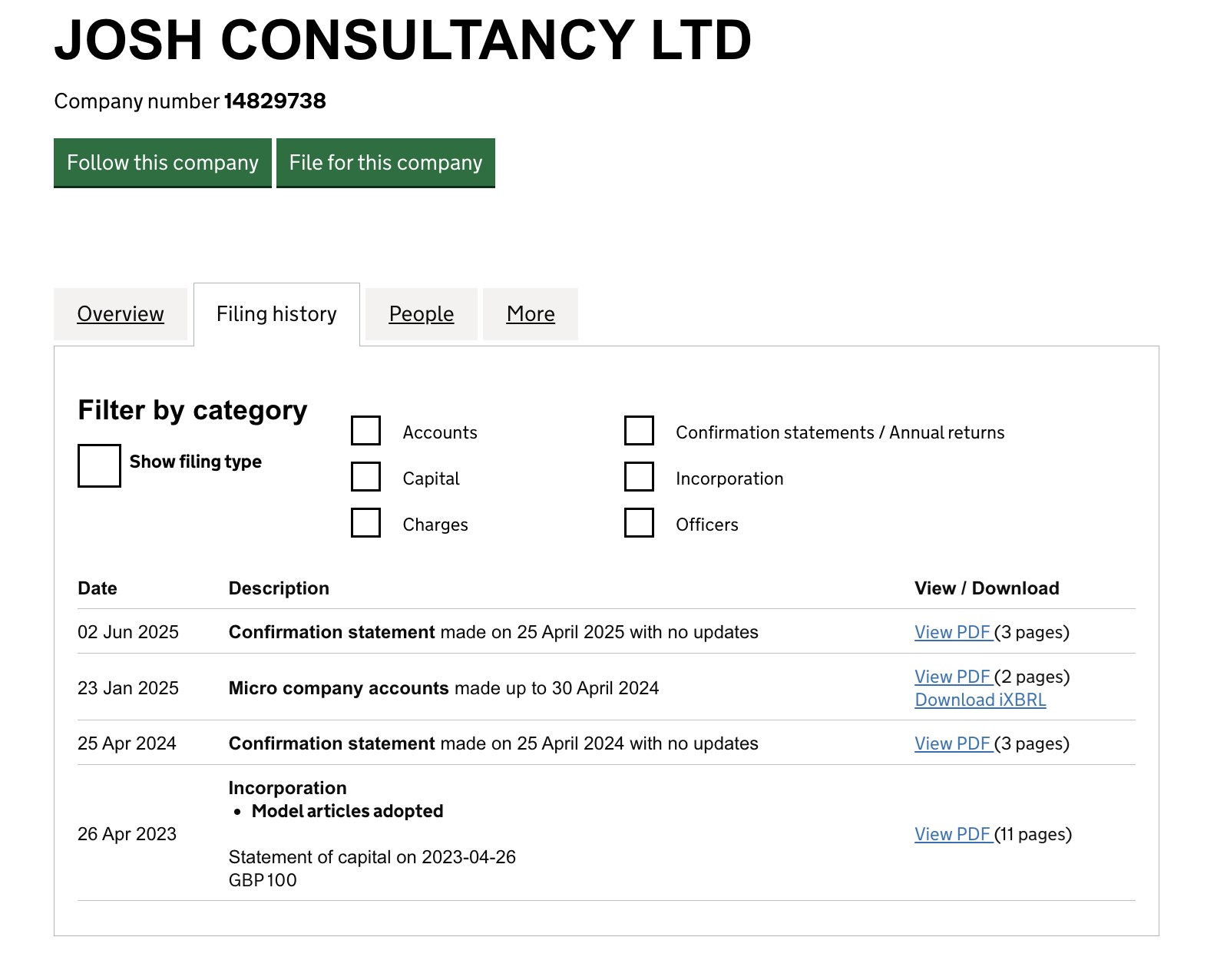

They’ve been in the game since 2023, and have filed accounts once as a micro company:

https://find-and-update.company-information.service.gov.uk/company/14829738/filing-history

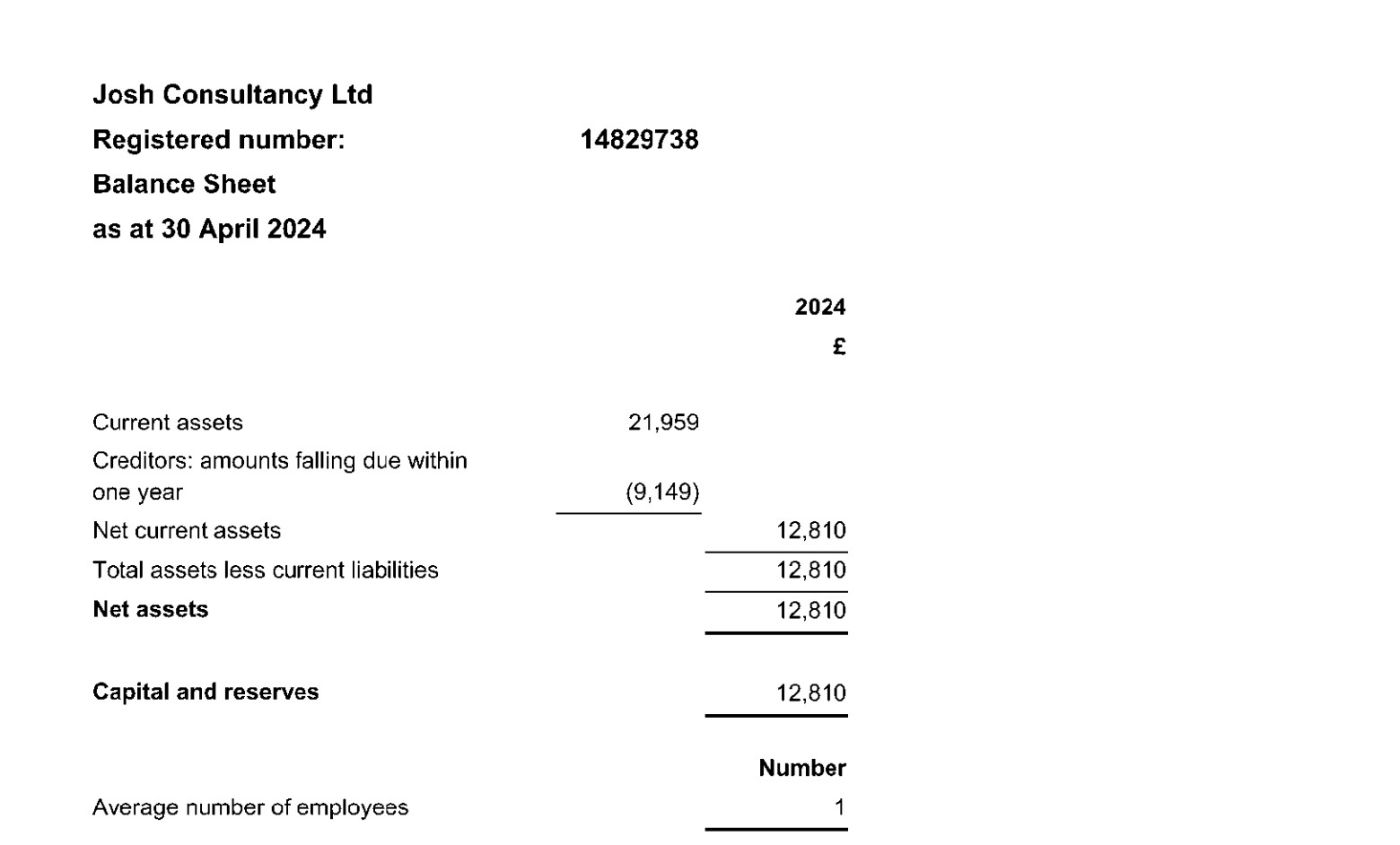

Those accounts list just £12,810 capital and reserves:

https://find-and-update.company-information.service.gov.uk/company/14829738/filing-history

That seems like slim pickings considering the client roster. It’s not just Solaxy, though there are plenty of those (this is less than half):

https://adstransparency.google.com/?origin=ata®ion=anywhere&domain=solaxy.io

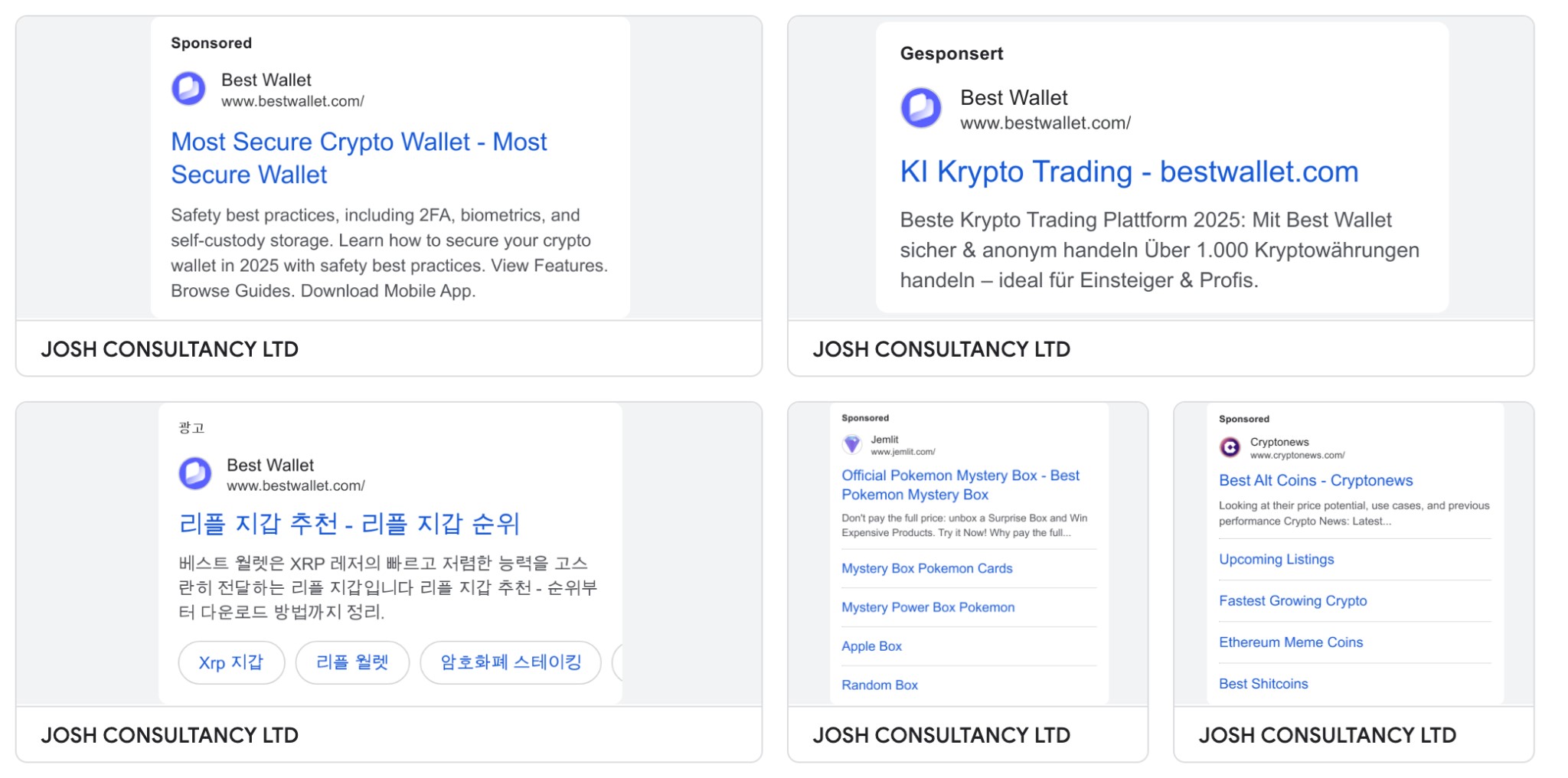

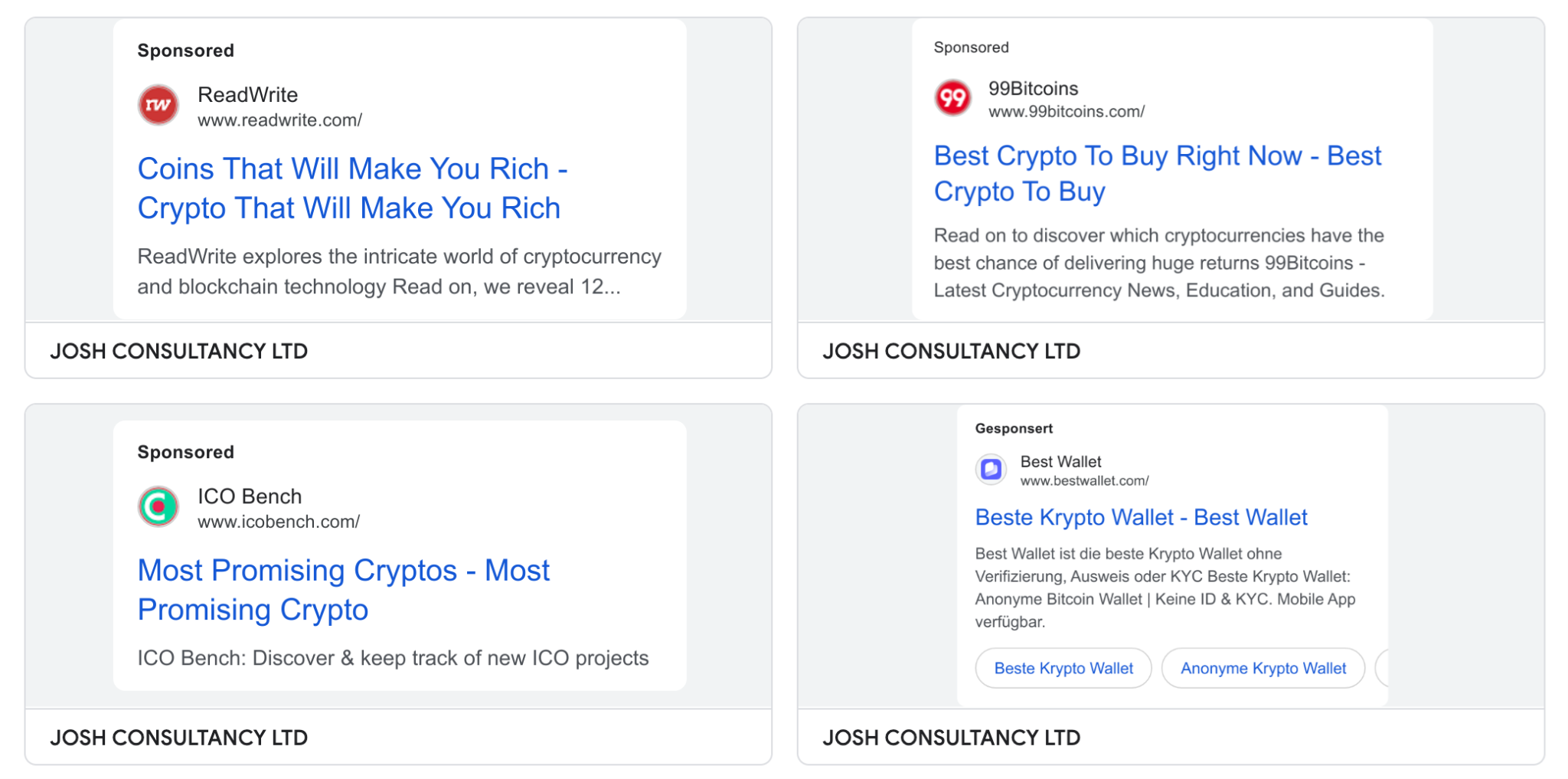

It’s also Readwrite, CryptoNews…

Best Wallet…

https://adstransparency.google.com/advertiser/AR10614553484952862721?origin=ata®ion=anywhere

99 Bitcoins. ICOBench.

https://adstransparency.google.com/advertiser/AR10614553484952862721?origin=ata®ion=anywhere

There were over 1,000 of them when I wrote the first draft of this article. Today, there are over 2,000 of them. Nearly every one is advertising a confirmed Finixio/Clickout team asset. How do you manage over a thousand crypto ads, then double the number in just a few weeks — all with just £12,000 in the bank

The norm with Finixio/Clickout operations is that top people in the company own or operate the different parts of the operation. Think Scott Ryder, CEO of Block Labs/Block Media, and also owner of the company that owns it, and also head of business development at Finixio. Or the way the core Finixio/Clickout team owns the wallet, developer, and law company the rest of the network uses.

So if we figured that like always, they’d keep it all in-house… who owns Josh Consultancy?

https://find-and-update.company-information.service.gov.uk/company/14829738/officers

One guy, two gigs.

Cool. So who is Suresh Chandra Joshi?

https://rocketreach.co/suresh-joshi-email_8005333

Well, he’s co-founder at Battle Infinity:

Following a token presale Battle Infinity’s promised thriving metaverse and vibrant token-based economy failed to materialize, and the website remains copyrighted © 2022 to ‘BATTLE INFINITY,’ an entity you’ll be shocked to learn isn’t registered in the UK (nor could we find it anywhere else, including the white paper…)

He’s probably not too bothered on a personal level since he’s also head of performance marketing and a partner at Finixio.

Business as usual.

Money: where it came from, where it went, and what it means

Accuranker and Ahrefs give us incredible insights into how integrated the whole network is. At the level of the people who actually work on it, certainly as far as marketing and promotions go, it’s the same business.

But what kind of business, exactly?

We thought we’d uncovered a business network that centred on crypto, with presales and unusual price movements suggesting ways that the companies behind it all might really be making their money.

But when we enlisted the help of a blockchain expert, we started to discover that there might be a lot more to it.

Typical crypto launches, especially for memecoins, feature what is called ‘presales,’ where tokens/coins are sold at a reduced rate in the runup to the launch of the project.

Obviously before the project is live the tokens don’t exist yet, so you’re actually buying tokens that will exist in the future (probably…).

Buying and selling futures is something the SEC is often interested in, especially if it’s done in the US without appropriate financial licensing, but that’s by the by.

It’s time to learn some boring finance.

Mixing and commingling

Commingling is when you take investments from person A and investments from person B and put them in the same bank account.

Whose money is it?

It’s like if I took €10 from you and €10 from someone else and put it all in my pocket. If you ask me for your money back, I can give it to you, but if you ask me who the money in my pocket belongs to, or which €10 came from which person, I probably can’t tell you.

In the same way if you take investments from hundreds of people, and pour it all into the same bank account?

Commingling.

In crypto, this is referred to as ‘mixing,’ stirring together funds from different sources to conceal their origins. For some purposes, this works best when it’s done anonymously.

When someone does something like this, the only way to tell for sure whose money is whose is by their own internal records, or the records kept by the exchanges used to do the mixing.

It’s totally different from how most transactions are handled on the blockchain.

CEX and DEX

Personally I find blockchain explorers as user-friendly, clear and simple as 5D chess in the Mariana Trench, but there’s no doubt that every transaction on a blockchain is permanently recorded in a public way.

Only destroying the blockchain itself could erase or tamper with that permanent, encrypted record.

However, it is possible to use centralized exchanges as mixers, especially large ones, because while they don’t take their funds off chain, they do commingle them. Darren Jackson of CrypTegridy assured us that this is one of the most effective methods of mixing.

Centralized exchanges (CEXs) are businesses that exist off the blockchain. They’re like a normal business with a normal website. Decentralized exchanges (DEXs) exist on the blockchain. A decentralized exchange connects your crypto wallet with someone else’s; a centralized exchange puts your crypto in their wallet, usually along with a lot of other people’s.

DEXs are peer to peer, and CEXs work like banking, where ‘your’ money is ‘in the bank,’ in theory.

In practice banks use something called fractional reserve banking, meaning they hold reserves (or in some countries, including the US, UK, Sweden, and Hong Kong, capital) equal to a proportion of the loans they issue and the deposits they’ve been given.

Meanwhile, ‘your’ money is in someone else’s house, car, or business, and if you go down to the bank and ask for it all back they will, in turn, give you ‘someone else’s’ money, all drawn from the same commingled fund. In law, when you put your money in the bank, you’re actually just agreeing to lend the bank that much money, which it then lends out to other people.

CEXs can also have this problem, made much worse because they’re largely unregulated. That can mean they don’t have enough reserves, and there’s no wider banking system for them to rely on (when banks’ commitments exceed their reserves they buy money from other banks; this happens all the time, but requires a network of cooperating institutions, which CEXs don’t have.)

Most importantly for our purposes, though, a CEX lets you stir your money up with other people’s, and only you and the exchange know where it all came from.

Which brings us to…

Keeping the income stream clean

So, imagine you have a lot of money (nice, stay here for a minute) and you don’t want people to know where you got it. You can’t just funnel it to where you want to store or spend it, because you can’t answer questions like ‘where did all this money come from?’

You need to send it out one way and have it come back clean.

Launder it, in other words.

What do you need?

One option is a small, cash business.

Barber shop?

Tick.

Landscaping company?

Check.

Bar? Nail salon?

Oh yes.

Bonus points if it’s a business with variable pricing for goods or services — one where you set your own prices, or where tipping is common.

Those kinds of businesses often give small-time crooks a place to cycle a few million a year into and out of cash registers and bank accounts so it comes up smelling, if not of roses, then at least like something that’s too much trouble for law enforcement and tax agencies to bother chasing.

But what if you had tens of millions, or hundreds of millions? You’d need to control a lot of bars to swing that.

Yes, if you’re Al Capone you can play that way. (Though it was taxes they got him on in the end.)

But if you’re not involved in ‘crime,’ per se, at that level — you just have all this dirty money? No dice.

What you need is a big commingled account with unreliable or scanty record keeping which you can then withdraw from anonymously and securely.

Something like a crypto presale, in fact.

Presales: Do your own commingling

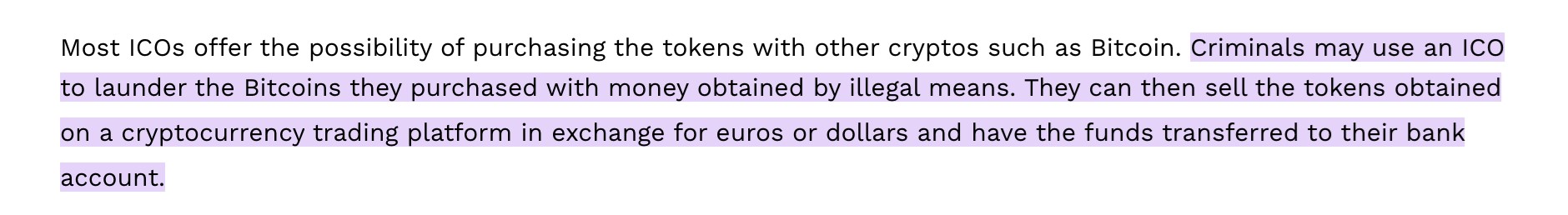

Our crypto analysis expert, Darren Jackson, has told us that there’s been moneylaundering hidden in the ICO, IPO and presales spaces since they began, and that this is common knowledge in the industry.

IOSCO warned of this back in 2017, amid concerns about underregulation, legit ICOs being accidentally used for money laundering, and…

https://financialcrimeacademy.org/financial-crime-risk-in-icos

Thanks, Financial Crime Academy.

ICOs (Initial Coin Offerings) were a buzz in 2018 and while many were just bad businesses and some were legit, many were pure scams. The scam often looked like it was, ‘take money from unsuspecting investors and give them nothing in return.’

I mean, it’s a classic.

But as the Dutch Authority for the Financial Markets noted in 2017, ‘most ICOs offer the possibility of purchasing the tokens with other cryptocurrencies such as Bitcoin,’ making it ‘very possible that criminals will use an ICO to launder the Bitcoins they purchased with money obtained by criminal means. They can then sell the tokens obtained on a trading platform for cryptocurrencies in exchange for euros or dollars, and have the money transferred to their bank account.’

We’ve looked at how that can work on the opposite end — the ‘mixing’ that happens when you move assets from a blockchain to a decentralized exchange is another example of commingling, where all your funds are commingled with the funds of other users of that exchange. Everything that comes out effectively has no traceable history.

Well, sort of.

From Binance, to Binance, via a sophisticated network

I’m thoroughly out of my depth on blockchain explorers; when it comes to managing sophisticated imaging of multiple interconnected financial flows on the blockchain you really want someone else to do it. So massive thanks once more to Darren Jackson, who put this together for me and walked me through it.

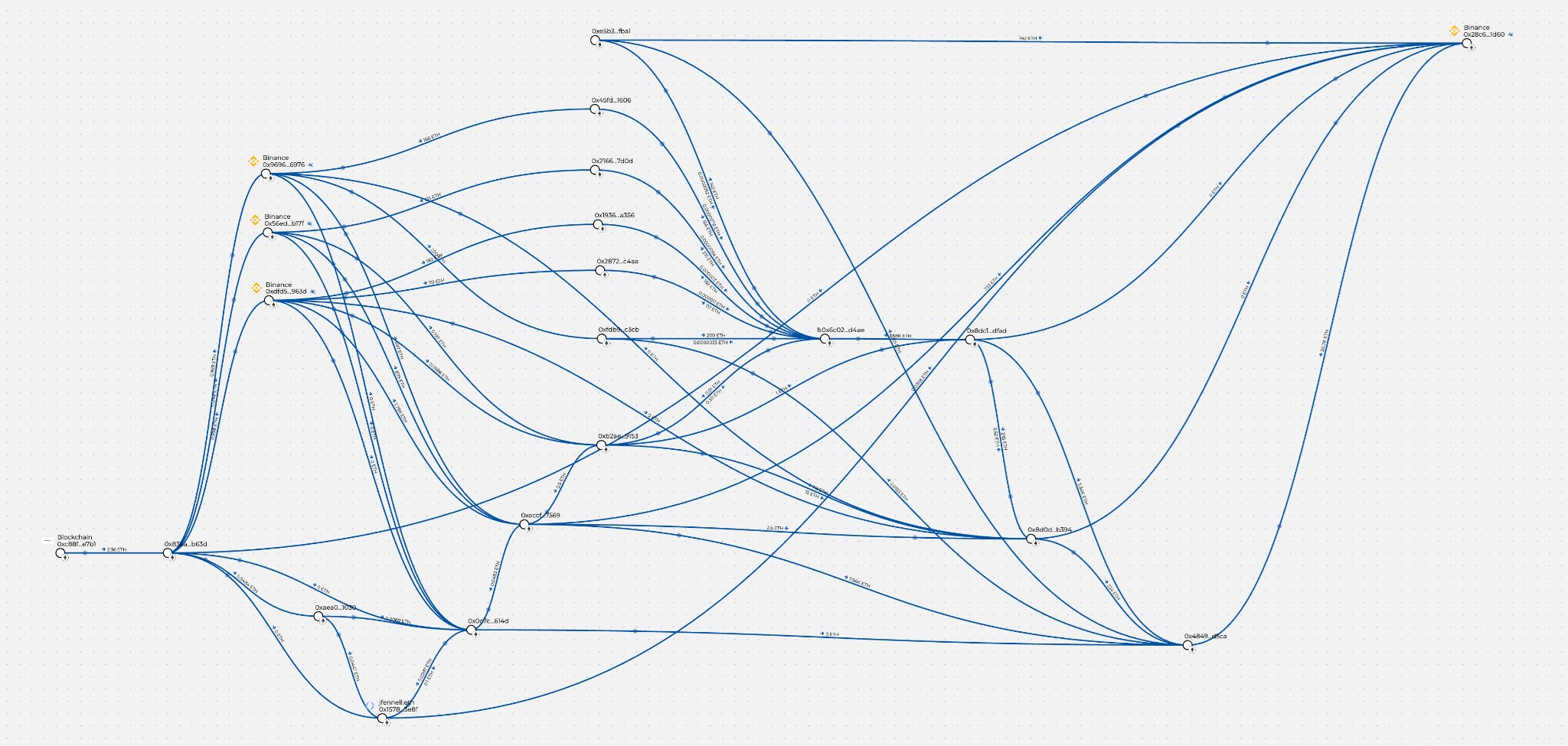

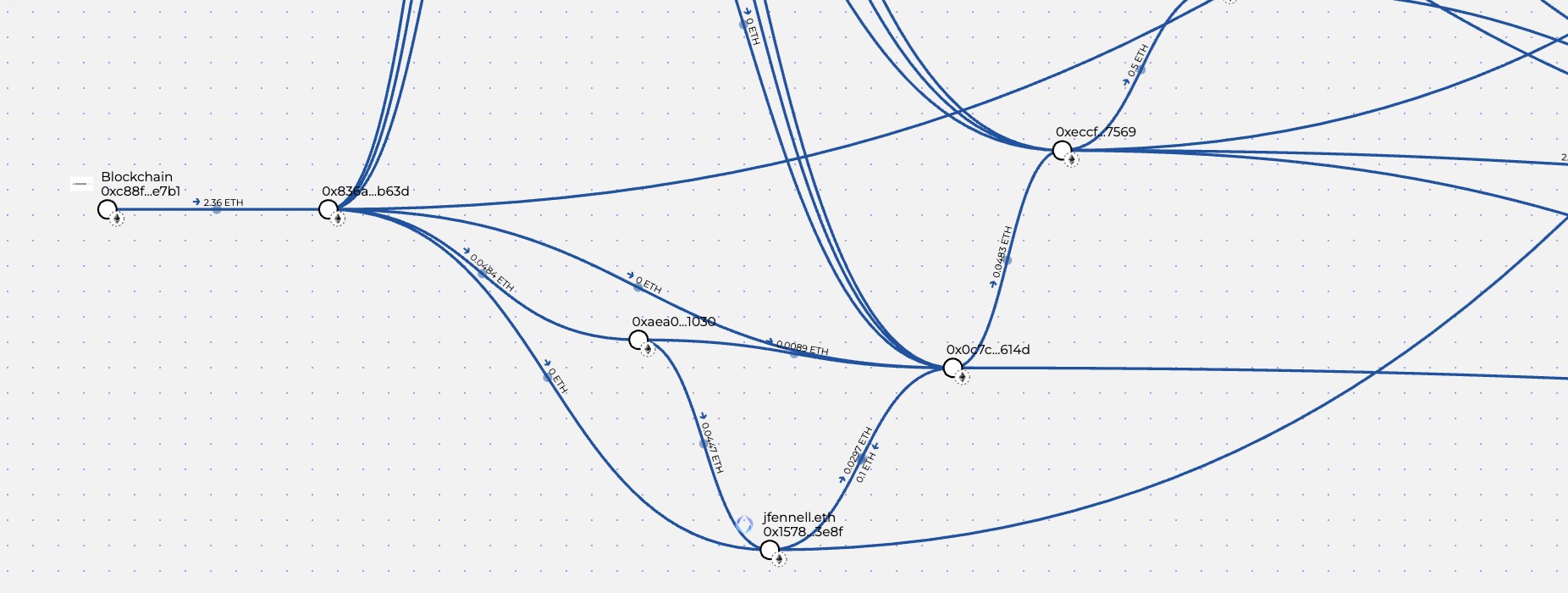

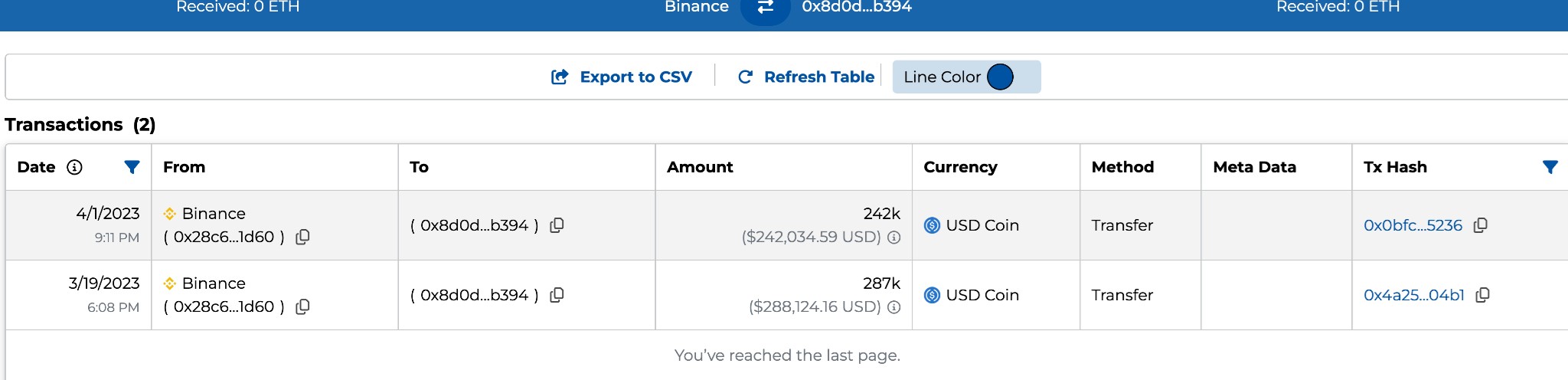

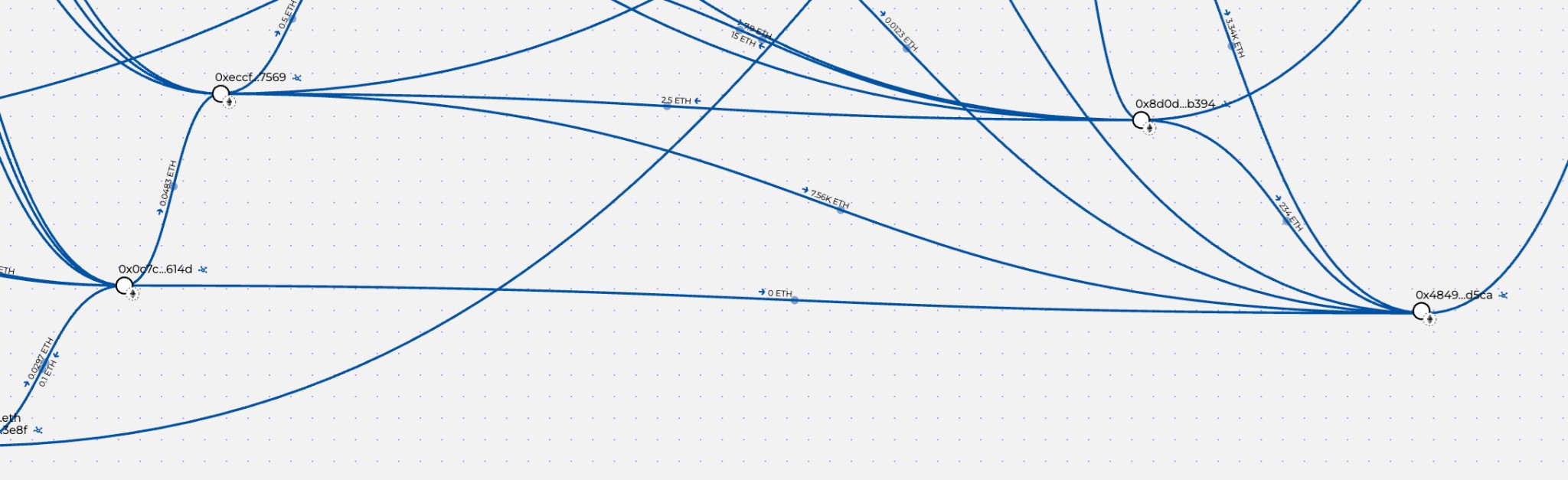

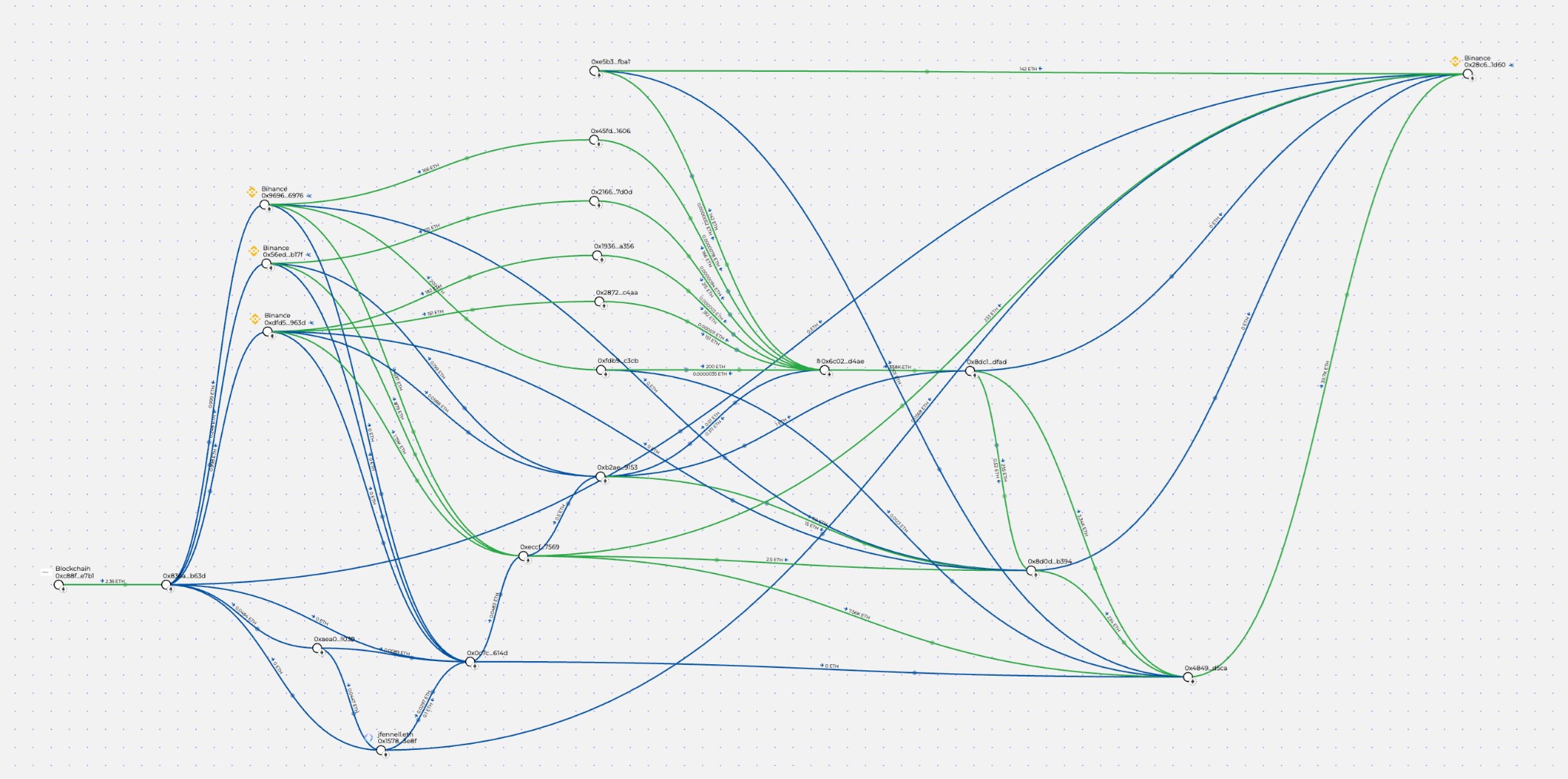

This image shows some of the financial flows through the network of assets owned or controlled by the Finixio team:

Another alternative is to go and use the tool that was used to create the image in the first place.

Go to breadcrumbs.app, create a free account, and then go to this link:

https://www.breadcrumbs.app/reports/17596

I’ll use screenshots of parts of the image to explain what we’re looking at.

Let’s start in the bottom left corner, with someone you’ll be familiar with if you’ve been reading these.

Over on the left there is the address ending …e7b1, which Darren previously identified as funding a Finixio project’s genesis transaction — the very first transaction.

It’s funding address 0x836a6b2e8bc2aba143f99a1803d03b05ce51b63d.

(And down there at the bottom is j.fennell.eth: James Fennell’s Ethereum address.)

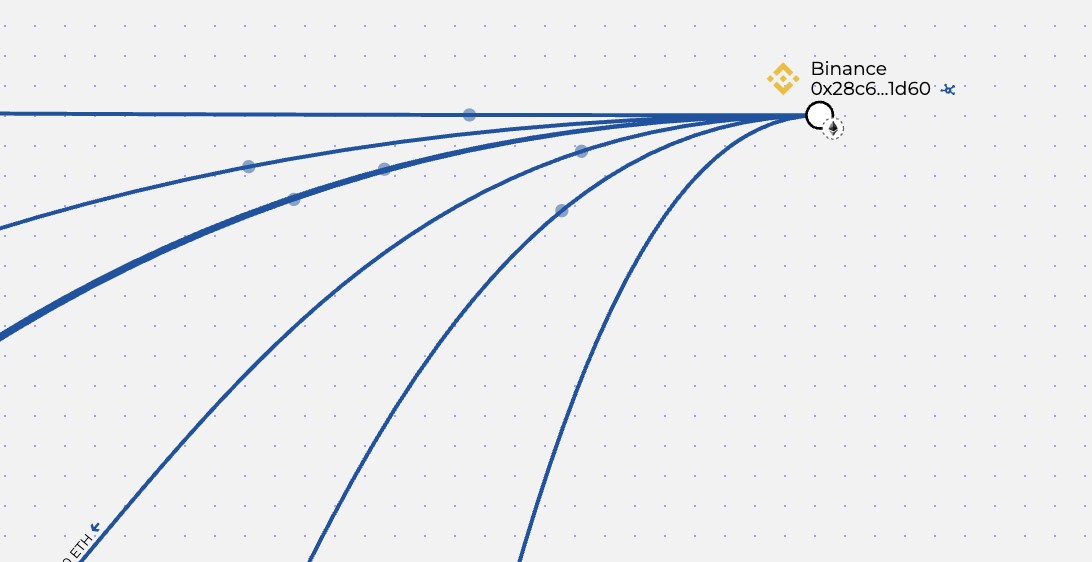

Now, let’s follow the next step of the connection. That’s a big swoop up to the address in the top right corner:

Ending in …1d60, that’s Binance 14, one of the Binance CEX’s addresses.

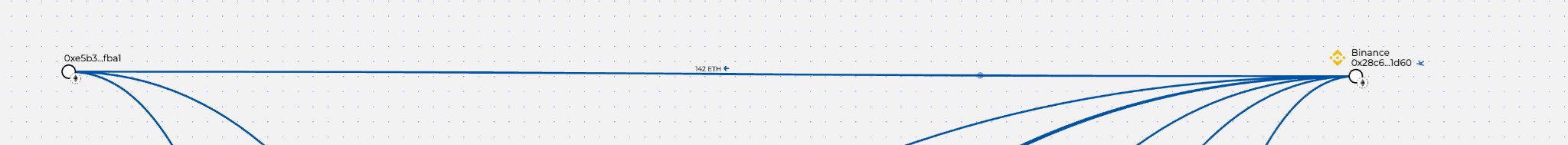

In fact, mostly funds come out of this address rather than going in. For instance, there’s this 142 ETH (€321,811) moving out to wallet 0xe5b38754a73fb4bc3f8f1233d1fd95629be3fba1.

Nearly every other line connecting Binance 14 to the rest of this network is also outgoing funds, typically in quite small amounts. However…

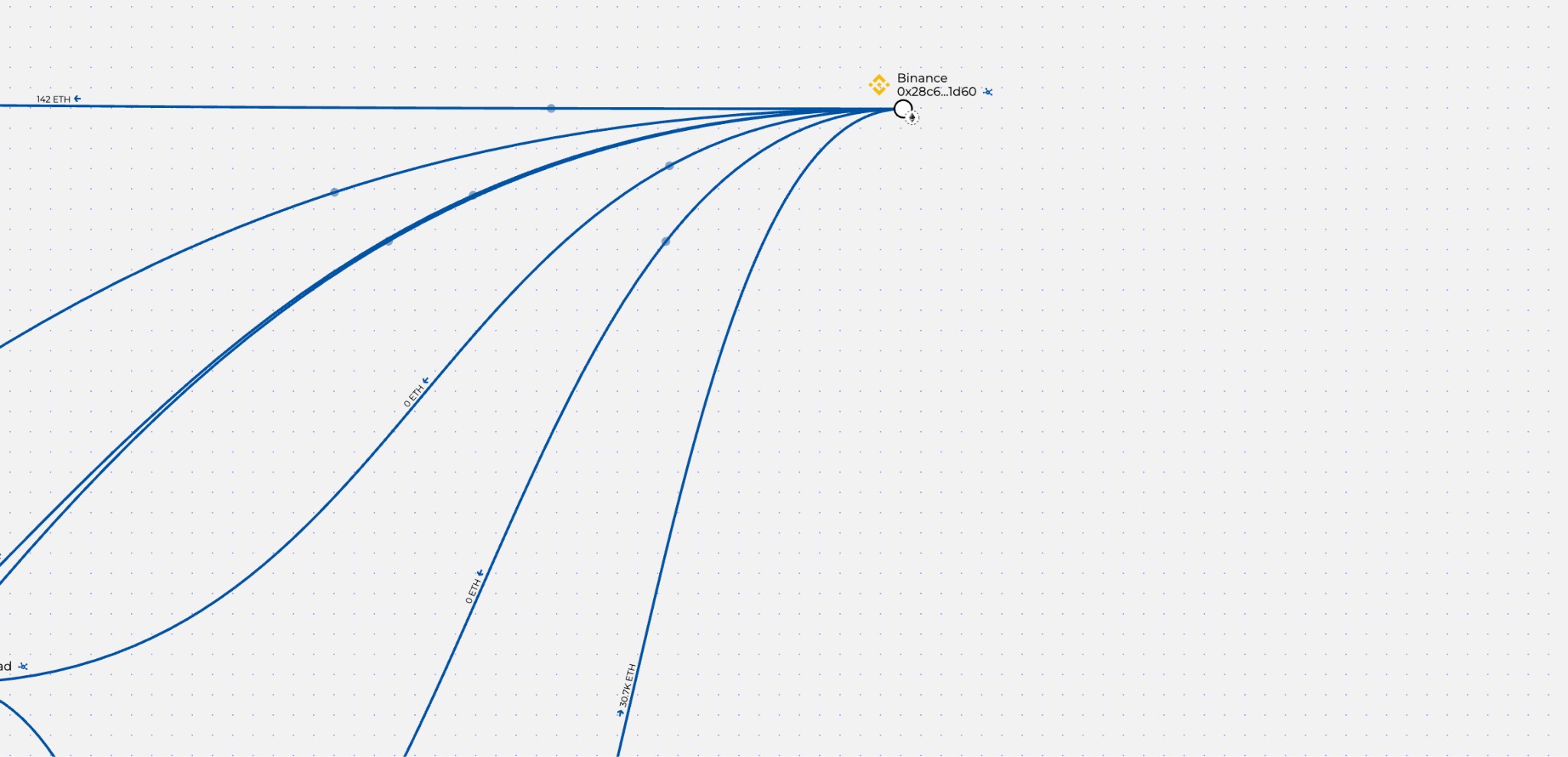

There’s a wallet down in the bottom right corner of our report sending 30 thousand ETH (€94,453,864) to Binance 14. That’s way, way more than is coming back out.

Outward flows are so small that with the exception of the first one we looked at, they barely register as involving any money at all.

In the case of one such outflow, that means:

In practice, then, ‘0ETH’ can mean anything up to half a million dollars (€430 000). It’s just that when €90 million is moving around elsewhere, it doesn’t make much sense to count the small change.

Back to that €90 million inflow. Where’s it all coming from?

0x48491f438fcb7b98b97c036627bac7b6af62d5ca.

A Binance deposit account.

So if Binance was a bank, this inflow would be money moving from the deposit window to the vault.

It’s a start. Where did this vast sum come from in the first place?

Moving from wallet 0xeccf6e64c46c87d422558bdab9bc4051d38f7569 to wallet 0x48491f438fcb7b98b97c036627bac7b6af62d5ca, 7.56 thousand ETH (€23,4578,887).

From wallet 0x8dc1d2138cb65e5b71f050754a71075b2c4bdfad to wallet 0x48491f438fcb7b98b97c036627bac7b6af62d5ca, 3,340 ETH (€10,309,124).

And from wallet 0x8dc1d2138cb65e5b71f050754a71075b2c4bdfad to wallet 0x8d0d31adec883af9dfc6ab131ab6cdd974f9b394, 235 ETH (€725,342).

234 ETH (€722,256) of that is forwarded to wallet 0x48491f438fcb7b98b97c036627bac7b6af62d5ca.

There are several other inflows to this wallet, all of which are relatively minor and marked on the main report as ‘0 ETH,’ though we’ve already seen what that means:

For instance.

So far we’ve followed individual connections around this network. But I think there might be a better way to look at it.

It means going back to look at the whole visual report again, so one more time: get ready to zoom in or join us at https://www.breadcrumbs.app/reports/17596.

Tracing the large transactions

All that’s happened here is I’ve flagged the transactions involving more than 1 ETH with green lines. Immediately, things are clearer.

But there’s a way to make it clearer still.

Here’s that same image, but this time, green lines mean all transaction flows above 1ETH that also originate in Binance wallets and end up in Binance 14.

Note that it looks more or less exactly the same as when I just flagged >1ETH transactions.

(It’s also based on transaction flows rather than detailed analysis of transactions.)

But from what we can see, this is a picture of 4,280 ETH coming out from three Binance wallets. 3,366 ETH then goes to wallet 0xeccf6e64c46c87d422558bdab9bc4051d38f7569, where 4,194 ETH is added.

We don’t know exactly what the source of this additional funding is, but we can say that this wallet is a private wallet address identified to us by our blockchain expert Darren Jackson as ‘the Finixio-controlled address,’ and it is the ultimate beneficial receiver of the Tamadoge presale, including funds totalling $19 million (€16.4). It appears that this is the wallet address that all Finixio/Clickout-team controlled presales ultimately ‘drain’ into.

This wallet also received 256 ETH from the Binance 14 address in the top right.

The most important takeaway here is that money from outside the system, in the form of income from presales, has joined with money that seems to be from inside the system, directly from Binance.

Money flows from the three Binance accounts on the left to either 0x6c022bd50aaaf1a851b63da854c660726b25d4ae (the Fight Out smart contract address; flows marked in orange) or 0xeccf6e64c46c87d422558bdab9bc4051d38f7569 (the private wallet address identified by CrypTegridy’s Darren Jackson as ‘the Finixio-controlled address’; flows marked in green).

From here, there’s another change.

Flows marked in red go from the green-marked network centred on 0x6c022bd50aaaf1a851b63da854c660726b25d4ae to wallet 0x48491f438fcb7b98b97c036627bac7b6af62d5ca.

The flow marked in purple goes from the orange-marked network centred on 0xeccf6e64c46c87d422558bdab9bc4051d38f7569 to wallet 0x48491f438fcb7b98b97c036627bac7b6af62d5ca.

From here, everything flows to Binance 14 (marked in yellow). That’s 30,000ETH — about €92,596,928.

But there are a couple of flows we haven’t really looked at.

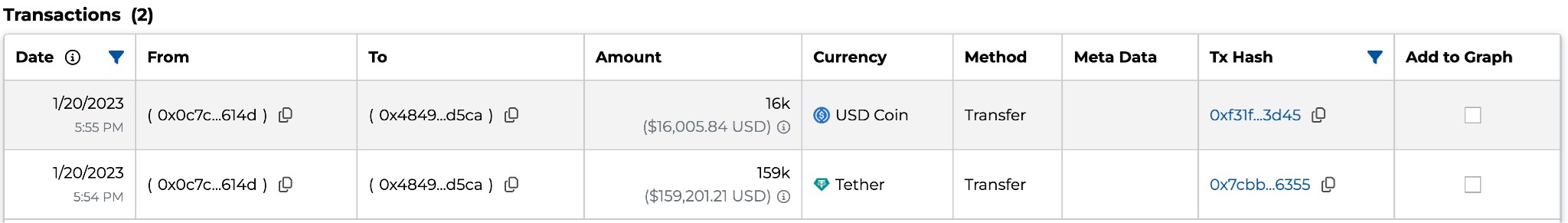

Recycling and moving funds around the network

First, there’s the 142ETH flow from Binance 14 to 0xe5b38754a73fb4bc3f8f1233d1fd95629be3fba1, right at the top of the image. Follow that and you’ll see 142ETH — exactly the same amount — flowing down from …3fba1 to 0x6c022bd50aaaf1a851b63da854c660726b25d4ae and right back into the mix.

But there’s also the secondary network of smaller transactions between multiple wallets. If you look at the image above, nearly every blue line represents the flow of money in relatively small sums, between wallets that eventually wind up sending their sub-1ETH balances to one of the big wallets. Eventually it all flows out of the same spigot at Binance 14, to be commingled in the holding wallet of a big exchange and have its history erased.

But remember when we pointed out where all this money comes in from? Some of it comes from presales and other active project income and almost certainly joins the network through the …7569 wallet. But the rest seems to enter the network via a small group of Binance addresses, flow through the system, and then exit to another Binance address.

So is it possible that, underneath the parasite SEO network, and underneath the crypto and gambling projects that lie below that, there’s another layer to the onion?

The most likely explanations for the flows we’ve seen include internal fund movements, simulations and tests, and trading — none of those quite fits the bill, though we do know that a lot of the financial flows Darren modelled for us are taking place between addresses controlled by the Finixio/Clickout team.

We asked Darren to explain further. He pointed out that the ‘in’ Binance addresses, where money flows into the system he modeled for us, are all ‘hot wallets.’ (A hot wallet is a wallet that is always connected to the internet, and presumably therefore in use. You don’t store a lot of crypto in a hot wallet, as a rule; that’s what a ‘cold wallet,’ which you connect only to make transfers, is for.)

These withdrawals are from multiple accounts, and Binance has simply used these addresses to facilitate withdrawals. It is this which makes tracing through an exchange impossible: the withdrawals all come from a small pool of addresses which forms the exchange hot wallet, and the process is the same for all crypto assets.

The deposit address, by contrast, is the one account receiving the assets. These are then swept back into the Binance hot wallet, and the address of that wallet varies depending on what kind of automation is used. Binance uses a tool called Fireblocks for automated sweeping and customer address management, and sweeping always takes place to a hot wallet; sweeping into a cold wallet would reveal assets that the exchange or its customers may prefer to leave undisclosed.

So much for the generalities. In the specific case we’re looking at, the sweeping of assets back into Binance 14 is mere coincidence. Their prior accumulation in the private wallet 0x48491f438fcb7b98b97c036627bac7b6af62d5ca is not. In Darren’s opinion, the confusing nature of the internal flows, with money moving between addresses and back in the same amounts, is obfuscatory.

In many cases addresses that made large withdrawals, and then bought tokens in the presales listed by various projects controlled by the Finixio team, never collected those tokens.

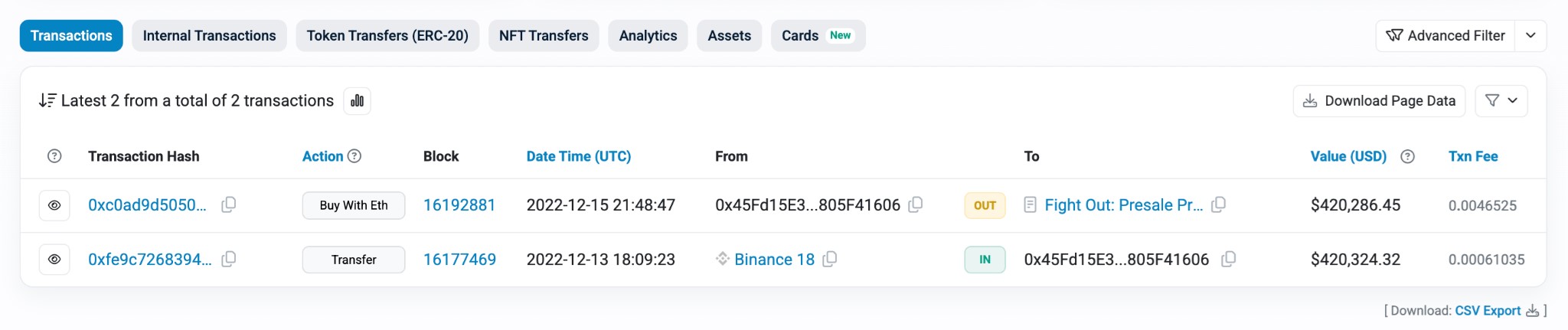

An example of that would be this transaction in the Fight Out presale:

https://etherscan.io/address/0x45fd15e3a47895f42b5ed5821deee81805f41606

Here, money has simply washed in and washed out. This is not a purchase in the conventional sense. Is it the use of a presale as obfuscation of funds?

Darren believes so. In his opinion, these types of transactions, and the financial flows he mapped for us, are characteristic of crypto networks used for money laundering.

One thing is for sure: There is a lot of money moving through these crypto projects.

Clickout/Finixio continue to buy up websites, launch tokens, and operate casinos. In fact, there’s more to that story that I haven’t published… yet. But outside of gambling and parasite SEO, there’s a real question here about the wider crypto space and the potential for large-scale money laundering and other financial crimes that’s way easier to hide than in the conventional financial networks.